Zora

Her feats as a circus performer drew worldwide acclaim. But when it came to leaving the spotlight it was to the Treasure Coast that Lucia Zora retreated

BY CATHERINE ENNS GRIGAS

Lucia Zora’s life was the stuff of legends.

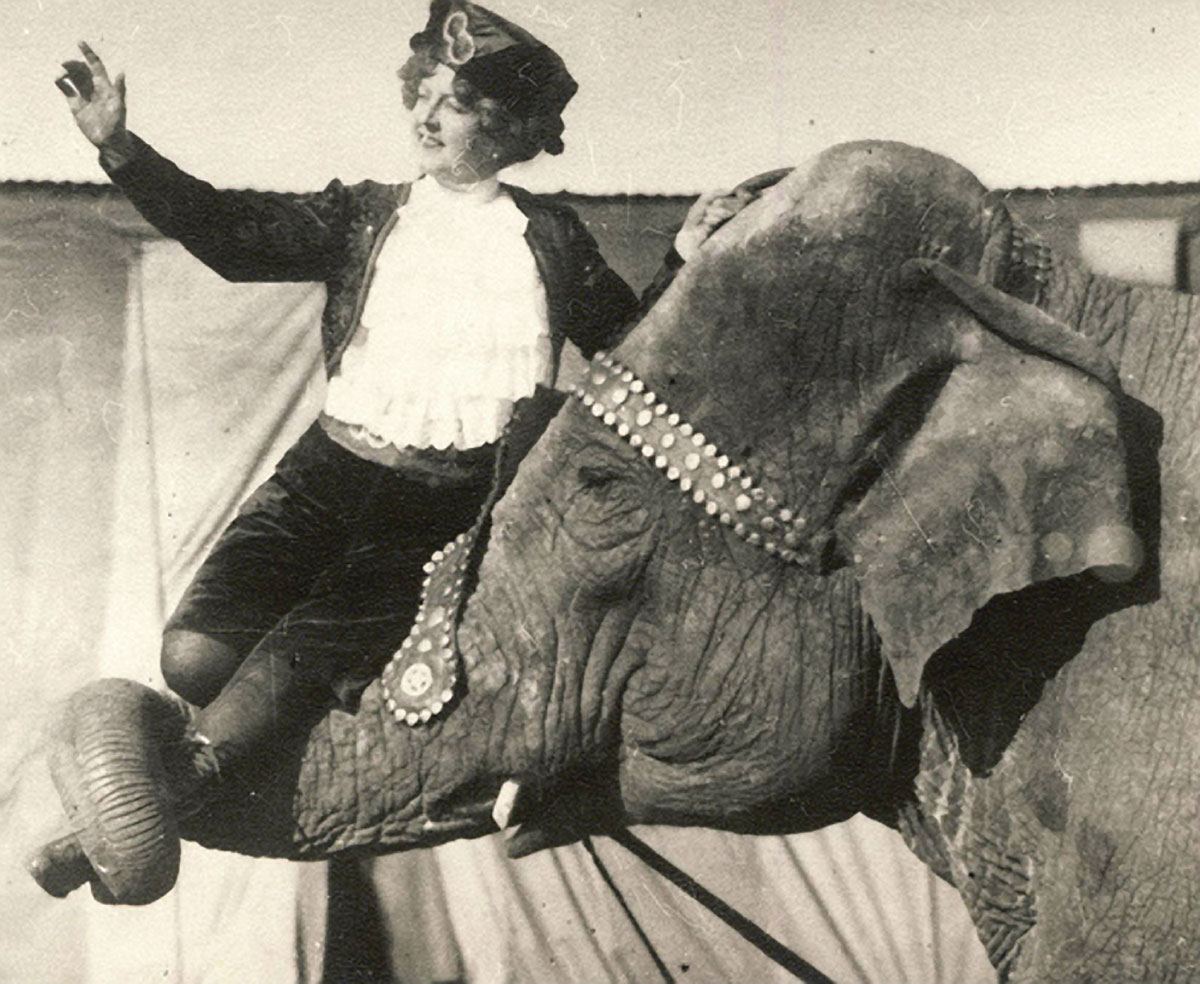

She might have been an Annie Oakley, or a Sarah Bernhardt — the ultimate female celebrities of her day — had her life gone a bit differently. In her time, she was famous, a celebrated circus performer billed as “the bravest woman in the world.” Daily, for more than a decade, she cast her fate in the cage, boldly bringing together lions and tigers in her famed wild animal act or balancing on the tusks of an elephant as it danced on its hind legs across the ring, mesmerizing the crowds.

CHECKERED LIFE

But, at the height of her celebrity, Lucia Zora retreated from her life under the Big Top to the Colorado wilderness. She sought solitude, and she certainly found it, but that life was harder and more lonely than she had expected.

So the woman known to the world as Lucia Zora left the wilderness and finally ended up in the house her parents had built on the banks of the Indian River south of Fort Pierce. There she lived out her life as a proper housewife, far from the greasepaint and sawdust, dying at the age of 59 in 1936.

Her name still brings a glimmer of recognition from long-time area residents, however. Zora’s fame may have been more fleeting than the other Zora, (Zora Neale Hurston, the writer) who also lived in Fort Pierce, but Lucia Zora’s life is at least as intriguing.

CARD FIRST

Who was she?

She began life as Lucia Card, born May 20, 1877, in Cazenovia, N.Y., the daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Milton E. Card. In the book she wrote about her life, “Sawdust and Solitude,” published by Little, Brown and Co. in 1924, she writes that she was named for a tramp steamer sitting in Boston harbor as her father returned home from an Arctic trip in order to be at her birth. It is more likely, however, that she was named after her grandmother Lucia.

In 1882, five years after her birth, the Cards bought property along the Indian River, perhaps at the suggestion of another Cazenovia resident, Peter P. Cobb. Card and his wife, Myra (Dey Bascom), became early local pioneers, planting pineapples along a wide swath of land by the Indian River. Their daughter spent little time in Fort Pierce. She was left in New York to be educated at the Cazenovia Seminary, at that time a nonsectarian boarding school that encouraged co-education.

REBELLIOUS ‘TOMBOY’

In her words, she was a “tomboy,” who rebelled against her “average conservative American home.” She was musical and could sing, but she dismissed that talent. “I studied,” she writes. “…but with never a thought of using that voice beyond speaking.”

In 1898, she spent time in Fort Pierce, staying with her mother at a camp on the Card property they called “El Selva,” or “The Jungle.” She occasionally entertained “the elite” of the pioneers, according to newspaper reports, as a “costume impersonator.” The locals were no doubt enthralled by the 21-year-old woman, who by all accounts was extremely beautiful and had already begun using her exotic stage name, Lucia Zora.

“…The curtain went up and divinely fair stood the beautiful Mademoiselle Zora,” a newspaper said. She so captivated the audience with her song that she raised $137.25, nearly $3,500 in today’s dollars. She turned it over to the “shell road committee” to build the first roads in Fort Pierce.

The local newspaper raved about another performance that showed where her sympathies lay in the Spanish-American War. Zora, dressed in a costume made from the Cuban flag, sang and danced to the song, “Cuban Captive,” against a backdrop of palm trees and two crossed “shining machetes” along with a banner emblazoned with the words, “Cuba Libre.”

“The entertainment at the city hall last Friday was a grand success… Mademoiselle Zora was greeted with rounds of applause, showing how popular this beautiful young actress has become, her part of the programme being carried out to perfection.”

DIRECTION CHANGE

During one of her trips north, Zora and her mother stopped in Jacksonville to see the Wilbur Opera Co., a traveling musical group. Zora apparently auditioned and won a spot, staying with it until 1902.

In her memoir, though, she writes that she ran away to join the circus at age 19. “The truth is that I ran away, coldly, deliberately, burning my bridges behind me, with a clear knowledge of what I was doing,” she says.

She says she abandoned the opera company in New Orleans, joining a small circus with the hopes that she would be able to work with the animals — an ambition she says she always had — but ended up in “generally useful” roles like dancing and horseback riding.

BAD TIMES

The circus went broke. Zora wrote that she ended up penniless and friendless in a strange city “frying flapjacks in the window of a second-rate restaurant.” She immediately began looking for another circus job without a thought of returning home.

“Years that were comparatively uneventful followed,” she writes.

They were not as uneventful as she said, however.

There were several newspaper accounts in October 1900 of a shooting involving Zora. The New York World reported that Joseph Pazen, the proprietor of the Pazen Theatre in Chicago, was shot and “probably fatally wounded” by “Zora Card,” described as a “burlesque actress.” The newspaper went on to describe her as “a tall, handsome blonde, a daughter of Milton Card, an orange grower at Ankona, Florida.” The account said she was married to William Hilliard, a leading man in a Chicago theater company.

The newspaper account was melodramatic, even for its time.“When arrested, she asked, ‘Is he dead?’ On being informed that he was still alive, she declared as she waved her hand dramatically in the air, ‘I wish I had killed him.’ ”

A report by the St. Louis, Mo., Republic has Zora Card accusing Pazen and another man, William Phelon, of conspiring to get her out of Chicago so “that she could not press a suit against Phelon for sending obscene literature through the mails.” She accused Pazen of conspiring to get rid of her and then called him a liar and an ex-convict. “Pazen told her to take it back, but she declined to do so, whereupon he caught her by the neck, choked her and bumped her head against the wall. She then pulled a revolver and shot him.”

Another music hall owner came to her defense, saying, “The girl has been deeply wronged.” It is not known if Zora ever faced criminal charges, or how the shooting victim, who received a bullet wound to his stomach, fared. But the newspaper account indicated that Zora felt no remorse over the shooting. “She says she does not regret her action, as she was only defending her honor.”

MARRIAGE

Life improved considerably for Zora when she joined the Sells-Floto Circus, one of more than 30 circuses crisscrossing the country at the time. Soon after, she met and married the superintendent of its menagerie, Fred Alispaw, a young man five years her junior.

The two animal lovers married quietly, but their adopted family celebrated the union in true circus fashion. As they began the nightly circus procession, the giant elephant that led the parade had a collection of old shoes tied to its tail and a banner on its side that read “Just Married.” Behind the elephant came a group of clowns dressed as the wedding party. The circus band played the Wedding March, and the audience showered Zora and her new husband with rice.

The bride ended up spending much of her time with the menagerie, and she confided in her husband that she wanted the “most spectacular elephant act in show business.” He obliged, but it was a frightening proposition to him, knowing that an elephant can weigh several tons and could crush his new bride in an instant.

PACHYDERM PROWESS

It was not one elephant, but many, that would pyramid above Zora, while she crouched at the bottom. She would lie under a carpet while every elephant in the circus stepped across her and then back. In another act, an elephant picked her up in its trunk and then whirled her away with all its strength.

Zora particularly came to love an elephant named Snyder, who she thought had a great sense of balance. She slowly and methodically taught Snyder to balance on his hind legs and walk the length of the tent. Then she taught him to walk while she balanced on a tusk. The spectacular act was born. She became the “Bravest Woman in the World,” riding on a tusk of the only elephant in the world that could walk like a man.

Bengal tigers and lions came next, and Zora began training them. When she entered the iron cage with her whip, with “death at my elbow,” she became one of the earliest female wild animal trainers and probably one of the first to use both lions and tigers, natural enemies, together. Between shows, Zora spent her time with domestic duties: reading cookbooks, making candy, studying French.

Zora, who went through “countless escapes” from the animals, recounted in her book how she watched in horror as a child stepped in front of a tiger, which killed it with a sweep of its claw. She was nearly killed by a tiger that tried to take her in its mouth, but was protected by the thick cotton of her cape. She suffered a lifelong injury from a jump she took off an elephant in order to avoid being crushed to death. There were train wrecks and several near-deadly scrapes with the animals for her husband, including an animal stampede.

A POWERFUL WOMAN

Zora remained undaunted. She seemed to have a mental, as well as a physical, superiority over every situation. She was described as a “powerful woman, both in physique and in mental dominance which became apparent with the first glance at her clear-cut features, her tight-fitting costume of high-laced Roman boots, black silk tights, Hussar coat of black and gold revealing the Junoesque proportions of a body which instinctively reminded one of the fabled Amazons.”

Zora herself knew she was physically up to the job, saying she was “160 pounds of strong muscle, bone and sinew.” While they lived with the circus, the Alispaws dreamed of leaving and settling down on a piece of property out West. They had saved up money, as well as diamonds, which the itinerant troupe used like a savings account.

‘NOT FOR ALL THE GOLD’

When they made the decision to leave, Zora declared that she would never return to the circus. “Not for all the gold that is beneath the moon,” she told a reporter.

Snyder, who was attached like a child to Zora, grieved and trumpeted for days after she left. “If an elephant loves you, he loves you with his soul, heart and hide,” she wrote. After a number of new trainers, Snyder finally rebelled. He went berserk and was put down in a blaze of gunfire, forever giving him the notorious label “Snyder, the man killer.”

In December 1917, the Alispaws traded their diamonds for homestead property in the mountains of northwest Colorado. They survived that first winter in a dirt-floor log cabin where solitude was the greatest danger.

CABIN FEVER

Zora admitted to a case of cabin fever so bad her husband hid the guns in a snowdrift. Circus life had meant living with other people around the clock. Now only Zora’s pet horses and a cow were around to keep them company.

The two rallied, however. Zora headed the local Red Cross and staged entertainments for the war effort. Their cabin became a showplace, filled with chintz-covered furniture and fine linens. She served meals made of vegetables from her garden.

Sometime between 1927 and 1930, the two left Colorado, however, moving to Fort Pierce. The reason is unclear. Perhaps they had run out of money, or they moved to care for Zora’s ailing mother. They lived on Oleander Boulevard near White City and then moved to the Card family home on South Indian River Drive around the time Zora’s mother died

in 1932.

FORT PIERCE DAYS

The Alispaws decorated the house with many mementos of the circus, including a lion-skin rug and an elephant-hide wall hanging.

Opal Freer Spencer, whose family lived near the Alispaws on South Indian River Drive, recalls their home: “What an awesome sight greeted you as you entered the front door and viewed a room that wrapped across the front of the house and down the south side to the kitchen. It was like a museum full of the most fascinating sights like pictures of Mr. Alispaw with his elephants, huge ostrich eggs and feathers, and a fabulous butterfly collection.”

She remembers Zora taking her to Sunday school in Walton and having a Christmas party with a tree decorated with real candles.

Zora threw herself into local life, joining the Woman’s Club and the Democratic Executive Committee.

Her circus life may have been a dim memory, but her love of animals remained, and the Alispaws even nursed a baby elephant that they kept in their backyard. After that the locals called their home “the elephant house.”

In 1934, the newspaper published a story she wrote about her dog, a black Skye terrier that befriended a lion cub the couple had raised during their circus days.

She died on Nov. 11, 1936, after months of illness.

JOURNEY’S END

“Death came,” her obituary said, “as the setting sun cast its lengthening shadows on palm-fringed Indian River, at her home a few miles south of Fort Pierce.”

Zora, it appears, had made her mark on Fort Pierce, if not on the circus world. “A woman lovable, fascinating, cultured; a woman actively interested in the commonplace things of her community; yet a woman of boundless fortitude and diversity of experience,” her obituary read.

Fred Alispaw eventually married Mary Esther Hoeflich, a Fort Pierce resident who continued to live in the house after his death in 1957.

Their house on Indian River Drive still stands and is little changed, a reminder of a bygone era and a woman who lived her life as “The Bravest Woman in the World.”

Jean Ellen Wilson, Linda Hudson Bailey and Anne Sinnott contributed information for this article.