War along the river

Bridge tenders may have lived a simple life, but there was danger

BY CHRISTINA TASCON

There was a time when bridge tenders weren’t just maintaining the safe passage of water and vehicle traffic. Other voluntary duties came in handy when World War II broke out.

Janet Walker Anderson and others who lived in the drawbridge houses in Indian River County knew what they did to help was more than just giving access across the river. Allowing people across was an important way to help keep the lines of communication open between the mainland and the barrier island.

Of course, back in the 1930s and well into the 1950s, there was not such separation between the haves and have nots. People were just doing what they could to make their families live comfortably, but they saw their future in the bridges.

WINTER BEACH

During World War II, however, the job of the bridge tender was vital to growth and the whole county’s survival. The small regional airport in Vero was selected to become the Naval Air Station in 1942, and aviators learned to fly and battle there in 1943. The entire East Coast of the U.S. was threatened by Germany with surveillance. The U.S. Coast Guard visited frequently and checked every car and inspected each boat number during the war.

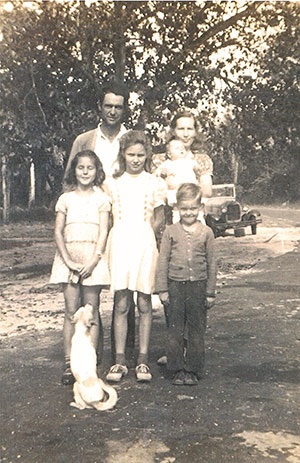

“I was about four years old when my father first brought me and my family to live on the river when we were caring for the Winter Beach Bridge,” says Anderson. “My father, William ‘Emmet’ Walker, was appointed by the county to get people over the bridge to fish or go in the ocean. There weren’t many people that lived over here, but I learned later that the night flying aviators were being watched from the German U-boats that were cruising the waters where we lived.”

Anderson says they enjoyed helping their father crank the lever to open the bridge and bring people from around 69th Street to Jungle Trail and vice versa. Between salting fish for visitors, bringing seafood to Sebastian and filling the family dinner table, Walker had his own boats docked at the river to take people out for a little pocket change.

“We lived on the barrier island side in a small house on land next to the bridge,” says Anderson. “I loved to follow my daddy around everywhere and catch fiddlers (tiny crabs) to sell as bait to the fishermen.

“There was always someone at the bridge, a cousin or an uncle. When they gave three short toots, they would open the bridge gate. Opening the bridge was fun, but we were required to keep the area clean as well as regular chores. We would play in the mangroves or climb trees with the Metz or Jones families, but we still had to take care of chickens and some goats that would headbutt you all the time.”

The young Walkers had to go to school in Vero. It took about an hour to pick up the students at the Wabasso Bridge along the way. The county would not allow them to go to the Wabasso School, which meant all three of the tenders’ kids knew each other.

WABASSO AND VERO BEACH BRIDGES

Unlike the other bridge, the Vero and Wabasso ones had the house on the property over the water. Whether it was one or two stories, the children played inside the home under their parents’ watchful eyes. They would not be allowed on the bridge itself until they went with their parents or were old enough to open the locks on the house door.

“We moved onto the hand-cranked Vero Beach drawbridge when I was only two weeks old in 1938,” says Janice Wood Sizemore. “We moved from the Vero Bridge to the Wabasso Bridge in 1951, just as I was learning to help my father with tending the gate. I always knew that we were different, but we were just being a family. My father encouraged us to be proud of it.”

COAST GUARD

In wartime, the German U-boats were found along the and ocean. Their parents did not talk about it in front of little Janet Walker, her older sister, Lena, and two young brothers, Huey and Dewey. They did not want to worry the children, so the children only talked when they were asleep or out of earshot.

They did discuss it with the men of the U.S. Coast Guard who were there almost every day, sometimes staying with the Walkers, eating freshly cooked fish that Elizabeth “Lizzy” Walker made or talking into the night. They spent time watching the submarines and tracking their movements so they could pass that information on to the Coast Guard. Every Model T and truck was inspected and the inhabitants interviewed by an official. A series of films made by the Indian River County Historical Society stated that it believed the work done by the tenders, military and patriotic residents would go down in history as helping to protect the coast in the war.

Through the hard work of local historian Ruth Stanbridge and the Indian River County Historical Society, a “Day on the Trail” is planned. Residents and guests will be able to visit historical sites and learn about the bridge tenders of the past.