Trafficking Shame

Local legend revealed first-hand account by last known survivor of the Atlantic slave trade in ‘Barracoon’

BY JANIE GOULD

African-American writer Zora Neale Hurston, who achieved prominence during the Harlem Renaissance by penning such classics as Their Eyes Were Watching God, left behind an unpublished manuscript when she died penniless in Fort Pierce in 1960.

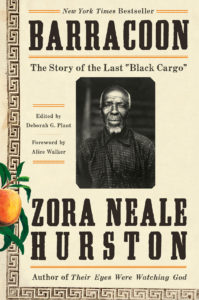

Now, more than 80 years after Hurston first submitted that manuscript to a publisher in 1931, Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo” is finally in print, adding to the legacy of one of Fort Pierce’s most important literary figures. It has become a New York Times bestseller and was named among the best nonfiction books of 2018 by Time magazine.

The novelist, folklorist and oral historian, a 1927 graduate of Barnard College in New York City, wrote four works of fiction, two books of folklore, an autobiography and numerous short stories and essays. After moving from Miami to Fort Pierce in 1957, she wrote for the Fort Pierce Chronicle newspaper and taught at Lincoln Park High School until poor health intervened.

Her grave at the Garden of Heavenly Rest Cemetery in Fort Pierce remained unmarked until African-American novelist Alice Walker, author of The Color Purple, discovered it in 1973 and inscribed the marker “Zora Neale Hurston: A Genius of the South.”

Younger readers soon discovered Hurston’s work and her intriguing life. The city established the Zora Neale Hurston Dust Tracks Heritage Trail to map out Hurston’s time in Fort Pierce and the Caribbean. It features three large kiosks, eight trail markers and an exhibit and information center. The annual Zora Fest in Fort Pierce attracts writers and fans eager to learn more about the author. St. Lucie County named the northwest Fort Pierce library branch in Hurston’s honor.

Great Britain and the U.S. had both outlawed trans-Atlantic slave trafficking early in the 19th century, but slave traders found ways to bring in nearly four million Africans from 1801 to 1866. The Africans were exchanged for “gold, guns and other European and American merchandise,” editor Deborah G. Plant writes in the introduction to Hurston’s newest book.

In 1927, Hurston traveled from her home in New York City to meet with 86-year-old Cudjo Lewis in Plateau, Alabama. He was the final survivor of the Clotilda, the last slave ship that delivered illicit human cargo from West Africa to the United States, in 1860. After the Civil War ended and slavery was abolished, Lewis married and raised a family in the small south Alabama town formerly known as Africatown.

Hurston sat down with Lewis multiple times over a three-month period. Sometimes, the former slave was more than willing to reminisce, but at other times, despite Hurston’s gifts of Georgia peaches, a Virginia ham or a can of Bee Brand mosquito repellant, he clammed up.

“Go leave me ’lone,” he said to Hurston after one unproductive session. “Cudjo tired.”

But on other occasions, he told Hurston heart-breaking stories about the capture of Africans by fellow Africans, about beheadings and gruesome torture. He said his memory of long-ago events was clear.

“I see the people gettee kill so fast,” he said. “De old ones dey try run away from the house but they dead by the door.”

As in her other books, Hurston lets Lewis speak in his own dialect. She often devises phonetic spellings to more closely match his pronunciations. For example, she spells Africa “Afficky” or “Affica.” The dialect might slow readers down, and I found it helpful to read some passages aloud as I made my way through the narrative.

Cudjo and 115 others were rounded up and taken to a holding pen on the Atlantic coast of Senegal known as a “barracoon,” Spanish for barracks. There, after being stripped of their clothes, they were forced to wait several weeks before boarding the Clotilda. Once aboard, they were herded to the hold, where they remained in total darkness for nearly two weeks.

“On the thirteenth day dey fetchee us up on the deck,” he tells Hurston. “We lookee and lookee and lookee and we doan see nothing but water. Where we come from we doan know. Where we was going we doan know.”

He described the ocean as fearsome, the waves as noisy as the growling “of a thousand beasts in the bush.”

“Cudjo suffer so on the ship,” he said. “Oh Lord! I so skeered on the sea.”

After 70 days, the ship made landfall near Mobile, Alabama, evading U.S. authorities by sailing under cover of darkness. Lewis and the others were taken off the ship, which was then burned and sunk. Eventually, the group was divided up and sold to plantation owners.

Hurston never found a publisher for her manuscript. Viking Press was troubled by her use of dialect rather than language, but Hurston refused to budge. The year was 1931, and fellow Harlem Renaissance writer Langston Hughes said, “Negroes were no longer in vogue.” He speculated that publishers were unwilling to take risks on “Negro material” during the Great Depression.

The ex-slave’s story contradicted what Hurston had always believed to be true: that Africans were captured by white people who went to Africa, “waved a red handkerchief at the Africans and lured them aboard ships and sailed away,” she wrote in her autobiography, Dust Tracks on a Road.

That’s why blacks might have had a problem with the book years ago, Walker said in the foreword.

“Who could face the vision of the violently cruel behavior of the ‘brethren’ and the ‘sistren’ who first captured our ancestors?” Walker wrote.

The book isn’t an easy read, but it is compelling, and adds greatly to our knowledge of African slave trafficking and its impact on the generations that followed.

Barracoon: The Story of the Last ‘Black Cargo’

Zora Neale Hurston

Amistad, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

New York

2018

Available at book stores, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Kobo and other outlets.