Talley’s way

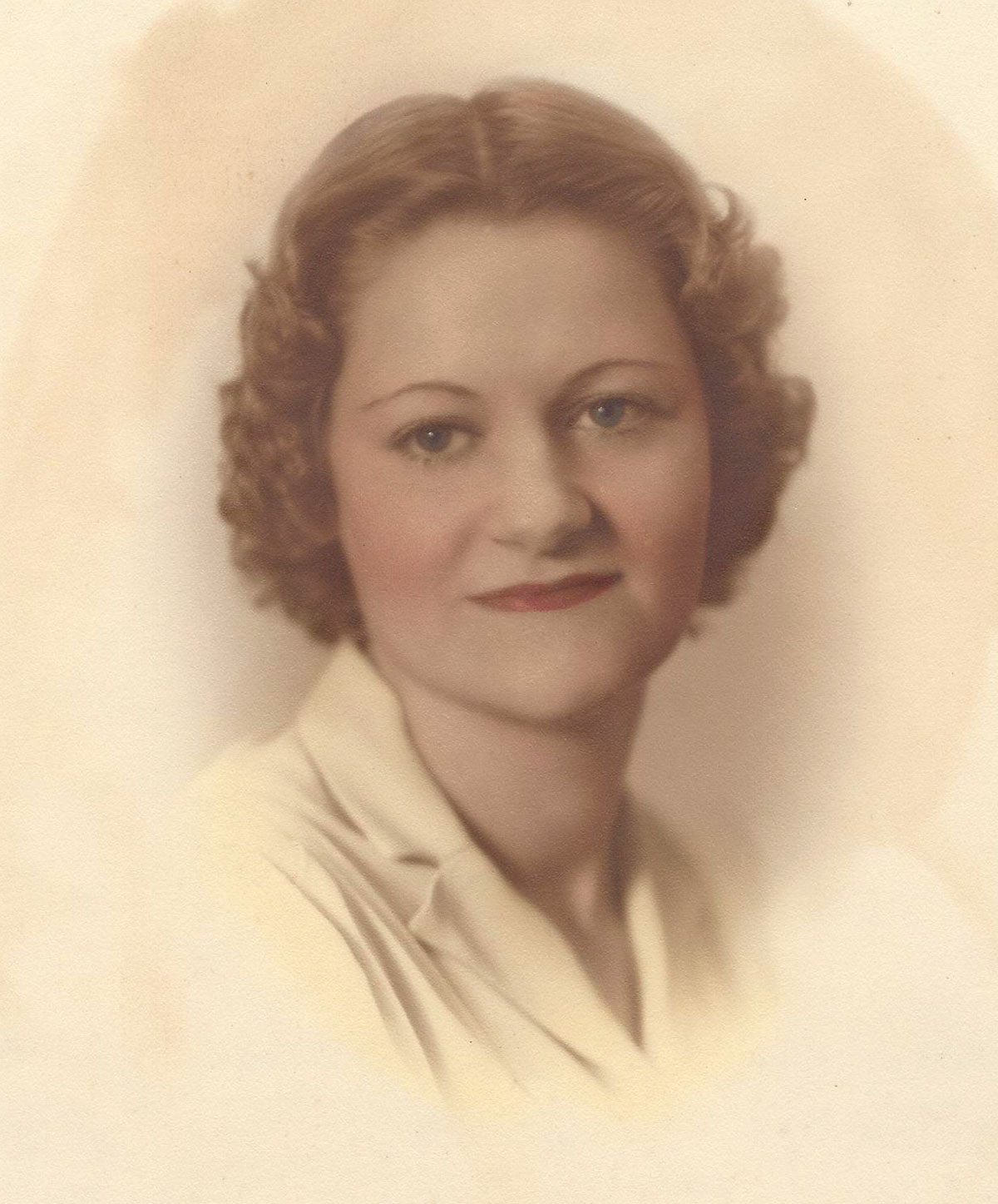

Talley McKewn Crary (1905-2002) moved to Stuart from Tampa in 1928.

A grandson recalls the life of a colorful political wife with influential connections

BY RICK CRARY

If people ever stop to wonder who used to live in Crary House, a congressional office in downtown Stuart, they usually learn it was the home of a man for whom a St. Lucie River bridge is named. These days his wife, who spent 66 years in that house, has been all but forgotten. But once upon a time in those quaint decades when Martin County was sparsely populated and everyone knew everyone else, Talley Crary, my grandmother, was a local celebrity in her own right.

It was Evans Crary Sr.’s decision to go into politics that forced his wife, Talley, into the limelight. Being in the public eye drew out the natural born actress she had hidden within. Although you always had to drag her to any social event, as soon as Talley arrived a light would flash on in her blue eyes — and the show would begin. She was always remarkably frank.

“I always have despised politics,” she said to audiences on many occasions. “And wouldn’t you know it — I’d marry someone who liked it.”

Evans spent 18 years in the Florida Legislature during the Treasure Coast’s formative years. He represented Martin County as a state representative, and then he represented a large chunk of the Treasure Coast as a state senator. At the pinnacle of his career, in 1945, he became Speaker of the House. So, there were countless cocktail parties and political receptions and, of course, a politician’s wife must always be on stage. When Talley took command with her disarming charm, she threw everyone off guard.

“When I was a young girl,” she would often say, “I was half afraid the white slavers would get me, and half afraid they wouldn’t.”

New acquaintances were surprised by such confessions, because something about Talley seemed positively Victorian. She was such a prim and proper Southern lady and yet she poked fun at the formalities to which she professed allegiance, as if to get even with the social conventions that restrained her.

“I’ve always been a rebel,” she’d announce, excusing herself whenever she felt she might have taken a step or two beyond the border of propriety.

Talley was truly the life of every party she attended. She was a great master of the fine art of conversation, because she understood that conversation is a team sport. Everyone present needs to be a participant, no matter how inept they feel. She knew how to make even the dullest visitors appear to shine and feel good about themselves. A lackluster comment from a guest was warmly received by her with encouraging delight. She would laugh with melodious glee whenever one of her guests said something halfway humorous.

Talley loved all the “trappings” of politics, as she called them, but she despised the campaigns and what it took to gain office. She had a kind of love-hate relationship with the political world and all of its attendant deceptions.

In her day, the wives of most of the state’s political leaders stayed at home, but not Talley. She frequently boasted of her decision to accompany her husband to Tallahassee, where she served as his secretary for a salary of $6 a day. She often said that when she first went up there, she took one look at all the “fancy girls” lined up in the Capitol building waiting to entertain the legislators, and she knew she couldn’t leave her husband alone. He was hers, and she didn’t plan to share him. With a wife as entertaining and as memorable as Talley, it’s no wonder Evans’ political star rose quickly.

Of all the descriptions I’ve heard of my grandmother’s social persona, the one that really hit the mark was when I heard somebody call Talley “a real firecracker.” That’s certainly what she was — in public. But as all great performers know, there is a life behind the scenes. Talley was not just a one, two, or even three-dimensional personality. She was a tangle of complexities which, at times, even she could not unravel. Solicitous to her stellar reputation to a fault, she kept her world behind the scenes almost entirely private. For Talley, being in the presence of others was nearly always synonymous with being on stage — but a part of her grew so weary of the show.

“Oh, good Godfrey, who is that?” she’d cry out whenever she heard someone pulling up in the driveway to her home, Crary House. But as she was complaining that she wasn’t in the mood for company, she was automatically patting the curls of her gray-and-white hair to make sure they were all in place. Moments later the intrusive visitors would enter to be hospitably entertained.

Talley always wanted to live in a perfect world. Of course, I believed in my grandmother’s ideals, and I assumed they were nurtured in the idyllic settings of her childhood. When I was young, I imagined she had lived in some Garden of Eden the modern world destroyed before I was born. I joined with her in lamenting its passing, and I was homesick for a place I had known only in our shared imagination.

Her favorite grandfather — the one she loved — had a plantation in South Carolina. Whether it was half as grand as Tara in “Gone With the Wind” or whether it was just a big farm in the middle of nowhere, it always seemed so much better than home. The old Confederate veteran, Papa Dukes, wore an air of nobility she craved. Maybe it was the respect he commanded as sheriff of Orangeburg County. Or maybe it was the way he sat at the top of those tall steps to his mansion as his sharecroppers bowed before him on payday. My grandmother always belonged to that plantation with its ambience of regal antebellum days.

Every now and then Talley would make statements that seemed out of place with the picture I’d acquired of our perfect past. The first, as I recall, was when she told me, “When I was a little girl, I used to hide in a corner of the house and read.” She said she would always run away into her books. She said she told herself when she was a child that she must have been adopted or kidnapped by the McKewns. Surely, she couldn’t have been a member of their family. They were so different from her, she told me. I began to wonder about thorns in the rosebushes of our perfect garden, but my probing questions elicited few details and no clear explanations.

Over the years we talked so many times about family history, about her recollections. I thought she had told me practically everything she could remember, but less than two years before her death she surprised me with some new revelations about her father. When she was about 14, she and her family moved into my grandfather’s neighborhood in Tampa. Their new house was two doors down from his. For most of her life, her future mother-in-law, Alice Lewis Crary, was her nemesis. They couldn’t stand each other. Every now and then, Talley would mention that Alice felt superior to the McKewns.

“How could she have possibly looked down on the McKewns?” I asked.

“Well,” my grandmother said with a sigh of resignation. “My father was a gambler. He played cards all the time, and sometimes he wouldn’t come home. And we’d worry that he might have lost his paycheck again. And how would we eat? Well, he won that last house we lived in. He won it in a game of cards. The man who lost the house, well, his son lived there. And Daddy evicted him with a crowbar. We were sitting in the car, and Mother screamed, ‘My God, don’t kill him!’ And we thought Daddy was going to kill him, but he moved out, and we moved in.”

With such a violent stir, it’s no wonder the neighbors had a bad impression of the new Irish family on the block. The incident also sheds some light on many of those questions I always had about why Talley said she wanted to run away from reality when she was a little girl.

When she was 22 she and Evans Crary eloped. It was on Feb. 4 , 1928. Talley and Evans had been dating off and on for seven years. The year before, Evans had moved across the state to become Stuart’s assistant city attorney. On a whim he decided to come back to Tampa for a weekend, after making a business trip to northern Florida. His car broke down near Dunellon, and he hitched a ride into the city. Talley met him at a drugstore after work. She was a legal secretary.

“Do you s’pose you could get off tomorrow?” Evans asked. “And get your car and drive me up to Dunellon? We’ll get married in Brooksville on the way up.”

That was how Evans proposed.

“I spent my honeymoon pulling his car back to Tampa,” she complained.

Afterward, Evans spent their wedding night at his parents’ house down the street without telling them a thing about his day. Talley went home to her house and told her mother. She couldn’t keep the big news a secret from her.

“Bless her heart,” Talley recalled. “She was so wonderful. She said, ‘Well, I would rather you not have done it that way, but if that’s what you want, why that’s all right.’ ”

In May of 1928, the couple announced their marriage, and Talley joined her husband in Stuart. Compared with the modern metropolis of Tampa, that tiny outpost was to Talley the outer edge of a muggy section of Siberia.

“I hated Stuart,” Talley confessed. “I had never lived in a small town like this where everybody knew everybody else’s business and talked about it. And Evans finally getting into politics, I had to be somewhat like Caesar’s wife — above reproach — and I wasn’t constituted that way. If I wanted to do something, I did it, which, of course, would bring the house of cards down on my head every time.”

Talley lobbied hard to get Evans to move back to the big city, but he wouldn’t budge. Instead, she stayed to become a prominent fixture in tiny Stuart, as her husband climbed the political ladder. In the 1950s, Evans wanted to run for governor, but Talley was having none of that. Eighteen years of statewide politics had been too much for her. So, my grandfather returned to the quiet shadows of Martin County to end his days practicing law in relative obscurity. By then, Talley and Evans had become great friends with the actress Frances Langford and her husband, Ralph Evinrude. They joined them on many weekend fishing expeditions on local waters, and in summer they cruised on the Great Lakes on the famous couple’s yacht: The Chanticleer.

In April of 1968, my grandmother’s brightest hopes ended. My grandfather passed away. Talley worshipped Evans, and when he was gone, she worshipped his memory even more. Her mother bore her widowhood for 46 years, and Talley endured hers for 34.

For four or five dark years my grandmother rarely consented to be cheery, but in 1972 her sister, Sophie, moved into Crary House. Sophie was the most relentlessly cheerful person I have ever known. She relieved my grandmother’s loneliness. Talley began to reacquire the sunny face she put on for the world. Then she was her old, entertaining self almost all of the time. Around town, Talley and her sister became such a famous pair that their names blended into one. How could anyone imagine Talley and Sophie apart? But Sophie left us in December of 1994.

In her mid-nineties, my grandmother told me she had finally realized her mortality. I was shocked. I marveled at my grandmother’s ability to make it for over nine decades without realizing the woeful bell might soon be tolling for her.

When grandmother was nearing death in July of 2002, I didn’t want to let her go. She had been an important fixture in my life for 47 years. More than anyone else, Talley gave me an understanding of the sense and the feel of history. She was my living link to the past. On my last visit to her, I sat on her bed and held her hand. Her eyes were closed much of the time, as she was struggling against the effects of some strong sedative.

Is there anything you haven’t told me, grandmother?” I asked.

“Ask me a question,” she said.

So many questions still revolved in my mind, but somehow it no longer seemed appropriate to dig deep enough to solve more family mysteries. Instead, I thought it best to simply hearken back to childhood memories of her grandfather’s plantation in South Carolina.

“Tell me about Orangeburg when you were a little girl,” I said.

“We went there every summer,” she said, dreamily.

“How did you get there?”

“On the train. We always rode on the train, except for that time we went up by car. That was quite a trip! My father got so mad. The car engine got so hot, the hood ornament melted. The first day we made it to White Springs.”

We talked about that trip and sights she saw along the way.

“When we got to Orangeburg,” she continued, “everyone came out to see us. We’d accomplished a great feat. I don’t know how we ever found our way. We didn’t have roads like today, and some of the rivers didn’t have bridges.”

Finally, I decided to leave her to rest with her pleasant childhood memories.

“I just can’t imagine a world that doesn’t have you in it, grandmother,” I said, in parting.

She opened her eyes halfway, and a tear rolled out.

“I’ll always be with you,” she said. “You just keep on being the same swell boy you’ve always been.”

Grandmother squeezed my hand tightly, and I squeezed hers. And as we let go of one another’s grasp, I realized we were saying our final goodbye. But I wonder — are there ever any real goodbyes for those few special people in our lives whom death can never take away? No, I don’t really think there are. In a way, I feel like Talley will always be there waiting, ready to entertain another impromptu visitor — just a little bit down the road.

An expanded version of this story appears in the author’s book, A Treasure We Call Home.