River of forgotten dreams

The Indian River, once known in the region as St. Lucie Sound, as seen from Old Fort Park in Fort Pierce. RICK CRARY PHOTO

Trials and tribulations of early St. Lucie settlers

BY RICK CRARY

“An antebellum colony arose on the Treasure Coast … and then it disappeared.”

In the age of Manifest Destiny, as America’s “multiplying millions” headed westward to conquer the continent, only trifling thousands set their sites on the Florida Territory. Of those, a few uncounted hundreds tried their luck on the Treasure Coast in the 1840s. At that time the area was part of a region best known for biting insects. It was called Mosquito County. If the adventurers’ dreams had come true, they would have transformed the wide riverfront from Sebastian down past Stuart into a land of tropical plantations.

After the United States took possession of Florida in 1821 from Spain, Indian troubles kept most pioneers away from the peninsula. President Andrew Jackson tried to force the Seminoles to move out West. In 1835, the Seminoles launched a counter-offensive to chase Americans out. That resulted in seven costly years of conflict known as the Florida War.

Soldiers spread the word back home that the territory was nothing but a load of worthless swamp. Soon the public wanted out of what was perceived as a useless war.

ARMED OCCUPATION ACT

In faraway Washington, men in power looked for ways to bring the troops back home. U.S. Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri came up with a plan. He was particularly interested, because volunteers from his home state suffered in the sawgrass with Zachary Taylor at the bloody Battle of Okeechobee. Benton’s solution was to drum up a bunch of land-hungry pioneers, loan them weapons and let them replace the troops. To lure applicants, the government would give heads of household a big piece of free land in a dangerous Indian buffer area, if they could hold onto it for five years.

“In the first place,” Sen. Benton explained, as reported in the Congressional Record, “it is the cheapest mode … Almost the only expense would be in the land … land that the settlers must conquer for us before we can give it to them.”

Benton’s proposed legislation was called the Armed Occupation Act, and it took Congress a few years to push through. By 1842, the War Department grew weary of wasting its diminishing budget trying to remove the last few hundred Seminoles from swamps surrounding Lake Okeechobee. President John Tyler bit the bullet and ended the Florida War in May 1842 “to reduce the demands upon the Treasury.”

“The further pursuit of these miserable beings by a large military force seems to be as injudicious as it is unavailing,” President Tyler proclaimed in a message to Congress. “[T]he Indian mode of warfare, their dispersed condition, and the very smallness of their number … render any further attempt to secure them by force impracticable …”

THE SOLDIERS GO HOME

Soldiers soon abandoned lonely outposts dotting the military maps, including a ramshackle fortification named Fort Pierce. Seminole chiefs like Billy Bowlegs and Sam Jones must have counted the mass retreat as a win. But now the plan in Washington was to send in random colonists with guns.

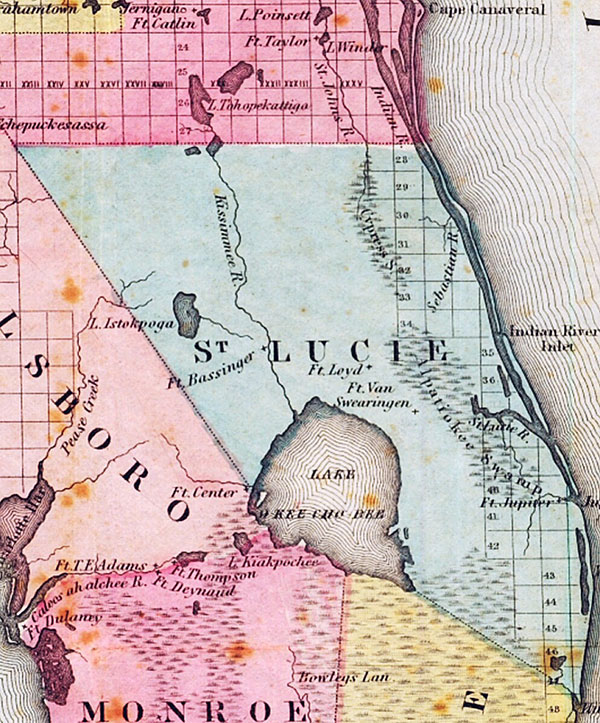

By the end of 1842, pioneers were filing permits to occupy 160-acre parcels of land in the treacherous Indian buffer, which included waterfront properties up and down St. Lucie Sound. St. Lucie Sound is what the Indian River was called on Zachary Taylor’s official military map back then — the portion that stretches between the Sebastian and St. Lucie rivers.

Who would be desperate enough to move to swamplands that were 200 miles away from the nearest place to purchase provisions? In those days there were no usable roads down the coast south of St. Augustine, and St. Augustine itself was only a shabby outpost of progress. Jacksonville was growing, but the nearest places with something close to culture were Savannah, Key West and Havana. St. Lucie Sound might as well have been a million miles away from civilization. The only way to get there was to paddle, or wait for a favorable wind to sail.

SETTLERS MOVE IN

America was in the grip of an economic depression that began in 1837. Hard times made some folks desperate enough to think free land in the middle of nowhere sounded like a golden opportunity. People like former banker Samuel H. Peck (permit holder #63). He helped talk a lot of folks from Augusta, Georgia, into joining him on a bold new venture in Mosquito County. Peck made it easy for his friends by providing transportation.

With the last scraps of his dwindling fortune, Peck invested in a schooner called the William Washington. He hired mariners and laborers and carpenters to start the new colony off with a bang. Some settlers brought slaves to do the heavy lifting. Unfortunately, there was only one inlet into St. Lucie Sound, and it wasn’t deep enough for a big schooner to safely get in and out. Colonists took their shovels and dug open a second inlet at Gilbert’s Bar in present-day Martin County, closer to Peck’s designated homestead. But that didn’t do the trick either.

Sometime early on, the William Washington got hopelessly wedged into a sandbar. Wreckers from Key West had to be hired to get the vessel unstuck. They towed it away until Peck could pay. When he couldn’t come up with the wrecking fee to get his schooner back, he folded his hand and moved to New Orleans where he signed up to fight in the Mexican War. Local boaters will recognize that he left his name behind on a small pocket of the Indian River, which is still called Peck’s Lake today. It lies south of the mouth of the St. Lucie River.

One of Peck’s carpenters was John Hutchinson (permit holder #157), whose grandfather James had acquired a 2,000-acre Spanish land grant in 1807, giving his name to Hutchinson Island. But James Hutchinson died before he could get his island properly surveyed. So, grandson John only staked out a claim for one of the 160-acre government-giveaway parcels.

Some of the colonists were invalids suffering from tuberculosis, including 27-year-old Caleb Brayton (permit holder #236). Brayton had moved from Fall River, Mass., to Augusta in hopes of finding healthier weather. Doctors told him the fresh salt air on Florida’s East Coast was more likely to extend his young life. Sadly for Brayton but fortunately for history, his wife, Marian, refused to come along. So, the lonely young man’s letters to home provide us with our best glimpses of daily life in the ill-fated colony.

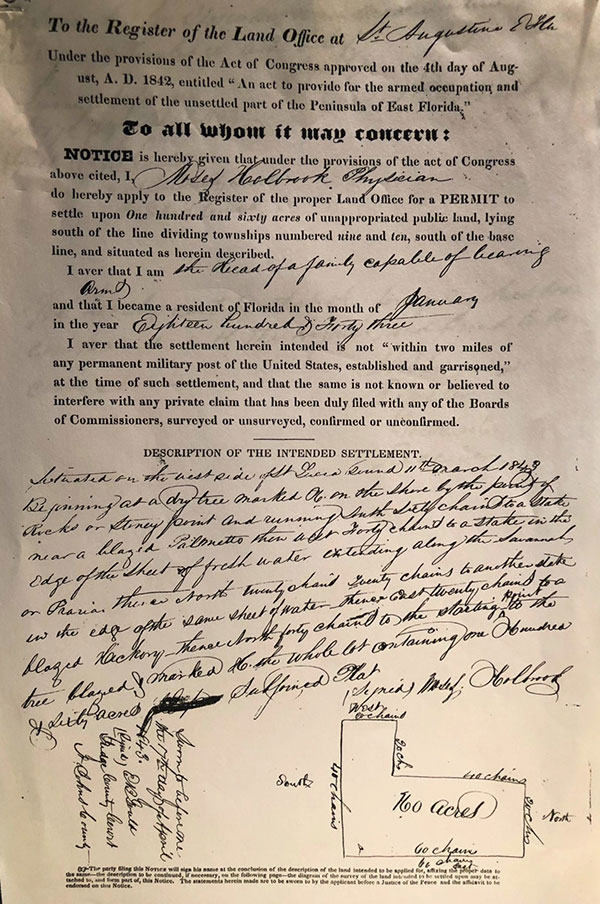

The sites of some early settlers with permits have never been discovered because of vague wording on the permits. For example, the permit for Moses Holbrook, who some believe resided for a year or so in present-day Ankona, describes his claim as being on the west side of St. Lucie Sound: “Beginning at a dry tree marked 06 on the shore by the point of rocks or stoney point and running south sixty chains to a stake near a blazed palmetto.”

A FUTURE GOVERNOR

There were also romantic adventurers like Ossian Hart (permit holder #62), whose hopes for the colony’s future swirled around what Hart called “the prospect of bringing forth and presenting to the world a new region of Tropical Country.” Hart was a scion of one of Florida’s first families. He had grown up on a 2,000-acre plantation in western Duval County called “Paradise.” His father, Isaiah D. Hart, co-founded the city of Jacksonville.

In the Florida Territory, few young men had enjoyed more privilege or received a better education than Ossian Hart. He was trained at the top prepratory school in the Old South: the Willington Academy in South Carolina, where John C. Calhoun had gone. So, the young lawyer might have been expected to cleave to the fineries of Southern culture, but an independent spirit persuaded him to help conquer a rugged region. Hart imagined a future when continual streams of ships would leave his tropical plantation “laden with the sweet orange [and] the well-flavored lemon as fine as ever grew in Sicily …”

THE BOARDING HOUSE

Frederick Weedon (permit holder #1) got the jump on everybody else. As a former Army surgeon in the recent Florida War, he had the inside track on snagging the abandoned fortress called Fort Pierce. That’s where he set up his new homestead. Dr. Weedon shrewdly calculated that the existing buildings could serve as a boarding house for other settlers moving into the area. They would need lodging and storage facilities while they cleared their palmetto-shrouded properties.

Weedon’s business acumen was the subject of widespread notoriety. He was the last physician to have tended Osceola on his deathbed. Somehow the good doctor ended up with the famous Seminole leader’s severed head, which he put on display at a drugstore in St. Augustine and charged admission to see. As far as anyone can tell, he did not bring Osceola’s head with him when he moved down to Fort Pierce.

Dr. Weedon’s boarding house experiment was short-lived. The kitchen at Fort Pierce caught fire on the night of December 12, 1843. Wind whipping in from the northwest spread the flames from roof to roof, and the whole place flared like a book of matches. Unfortunately, Ossian Hart and his brand-new bride, Kate, were storing a year’s worth of provisions in the fort when it burned down, not to mention their wedding gifts. The unhappy couple retreated to seek solace from friends in Key West. But Hart wasn’t about to let one major disaster chase his dreams away, so the heroic newlyweds returned to slug it out.

ESTABLISHING A COLONY

A customs house was set up at Indian River Inlet, which was located where Pepper Park is today. Shifting sandbars made the entrance especially treacherous. William F. Russell from North Carolina, referred to by some as Major and others as Colonel, became the inspector at the post. Russell never filed for a land permit himself. He seems to have resided on property claimed by his brother-in-law, John Barker (permit holder #69), a justice of the peace.

In spite of early troubles, by February 1844 there were enough new residents for Dr. Moses Holbrook (permit holder #56) to summon a convention. At 62, Holbrook was by far the oldest among the settlers. He brought hundreds of books down from his home in Charleston and stuffed them into a palm-thatched cottage. At the convention the colonists formed a militia called the St. Lucie Riflemen. At least 50 men signed up to defend the colony.

Although most historians call the intrepid venture the Indian River Settlement, St. Lucie seems to have been the preferred name the colonists attached to their endeavor. In March 1844, a territorial council carved out a big chunk of Mosquito County and named it St. Lucie County. The boundaries included the present-day Treasure Coast. Samuel Peck, whose boat problems had yet to take him down, was chosen as county judge. Caleb Brayton became the county clerk.

The following November, Ossian Hart was elected as St. Lucie County’s first representative in Tallahassee. Reluctantly, he left his 21-year-old wife behind for several months while he attended the territorial legislature’s final session. Hart fought to solidify St. Lucie’s standing as a county, and he voted against statehood for Florida. That’s because he didn’t want to lose all the extra federal dollars a U.S. territory could claim. But with Iowa in line to become a new Free State, Hart’s opponents were anxious for underpopulated Florida to join the Union as a Slave State. In the increasingly hostile halls of Congress, Southerners struggled to maintain a tenuous balance of power in the U.S. Senate.

INDIAN NEIGHBORS

As Florida entered the Union in 1845, the hopeful colony on St. Lucie Sound was a full-blown county — on paper. There wasn’t a courthouse or a jail. They had no roads, no theater, no church, no wharf, no regular mail — no nothing. Well, John Barker may have had a trading post where he sold whiskey to the Indians.

Happily, the Indians had been friendly so far. Although they were supposed to stay on the western side of Lake Okeechobee, Seminoles became frequent visitors on the banks of St. Lucie Sound. Sometimes as many as a hundred would congregate at the house of Mills O. Burnham (permit holder #59), which was in present-day Ankona. Burnham was the colony’s gunsmith. Indians traded their wilderness wares with him, and he would get their rifles in good shape.

In 1844, the Treasure Coast was part of the original St. Lucie County formed by a territorial council. Then, in 1855 the name was changed to Brevard. FLORIDA MEMORY

THE HURRICANE

An 1844 petition asking Congress to build a road from St. Augustine to “St. Lucia on St. Lucia Sound” claimed there were “Twelve hundred Souls” in the vicinity. If that is true, that would have been the highwater mark population-wise. Records are scattered and inexact as to when most people came and left.

In October 1846, a tremendous hurricane struck the area. High winds and water ruined Ossian and Kate Hart’s two-room log cabin. Their young orange grove was blown to pieces. It was one too many disasters for the young couple. Most other settlers must have felt the same. By the time the tax roll came out in 1847, there were only 24 men over the age of 18 left in the entire county. Obviously, a mass exodus had occurred, and with each departure — one more untold dream.

Mills Burnham stayed on as the county’s sheriff and its representative in Tallahassee. Caleb Brayton remained for the sake of his ailing lungs. He hired an Indian hunter and boasted to Marian that he dined on turkey and venison every day. Relentlessly, Brayton tried to persuade his wife, Marian, to join him, but telling her about the mosquitos could not have helped his cause.

“Tis true, four months in the year (from June to October) they are almost unendurable here,” Brayton wrote, “but the other eight there was never a more delightful place to live.”

SEMINOLE UPRISING

Then came the fateful day that caused a panic, which made national news and helped set back development of South Florida until well after the Civil War. It was Thursday, July 12, 1849. Lonely Caleb Brayton had spent the night with William F. Russell and his family. Four Seminole Indians showed up for breakfast. The Russells knew two of their impromptu visitors as Sammy and Eli. A government Indian agent would later identify all four by their Seminole names: Seh-tai-gee, Kotsa Eleo Hajo, Hoithlemathla Hajo and Panukee.

As the day progressed, the Indians went to the nearby house of D.H. Gattis, a 31-year-old farmer from Alabama. Like Major Russell, Gattis was not a permit claimant. He owned a grinding stone, and the Indians wanted to hone their knives. After their blades were good and sharp, the Indians returned to the Russells’ place and played with the children. They laughed and gave them rings and other presents made from beads. Nothing seemed unusual.

Russell looked off in the distance and saw his brother-in-law, John Barker, come out from his house to the field. He walked away to chat with him. That’s when the Indians said their friendly goodbyes to Susan Russell and her six kids. They followed her husband out into the field.

According to depositions reported in newspapers, plus Caleb Brayton’s account to his wife, the Seminoles suddenly and inexplicably raised their rifles and fired from very close range. They must have all been aiming at Russell, unless they were terrible shots, because they hit him three times. One musket ball broke the lower bone of the left arm he would lose to a surgeon’s saw in St. Augustine. The other bullets merely grazed his abdomen. Instantly, Russell ran toward Gattis’s house for help. Barker raced toward home, but he couldn’t run fast enough. All four Indians overtook him, and then they stabbed him to death with their freshly sharpened knives.

PANIC AND EVACUATION

Pandemonium erupted after that. None of the settlers’ guns were ready to shoot. Everybody ran in all directions. Wives, kids, slaves. Some hid in the woods, others jumped into boats. Those in the boats, like Caleb Brayton, felt like sitting ducks. Indians took potshots at them. Brayton thought he counted eight Seminoles firing from the shore. A black man next to him was hit in the sleeve. Seminoles reloaded and fired until the boats were out of range. Then the attackers looted the houses and burned one of them down.

All that night, Brayton sailed up and down the settlement warning the rest of the settlers of the Indian attack. Everyone else was too scared to go near shore, so Brayton quietly waded in from neck-deep water at each neighbor’s homestead. The next day, the entire colony was evacuating up the coast. By July 25, Brayton reached a sugar plantation called Dunlawton near New Smyrna, from where he wrote a frantic letter to his wife.

Seminoles struck again the next week on the other side of the state near present-day Wauchula, killing two men and wounding a married couple at a trading post. With two attacks close at hand, settlers in the statewide Indian buffer panicked and abandoned their cabins. Floridians were certain the Seminoles were starting another war. They demanded massive numbers of federal troops.

JUSTICE DENIED

President Zachary Taylor knew a thing or two about Florida from his days as a commander in the Florida War. He and his administration believed the killings were just ordinary murders — not a genuine Indian uprising. Well, that opinion made Floridians go crazy. Political heat was turned up high enough to force Taylor to send in 2,000 troops headed by General David E. Twiggs.

Contrary to Floridians’ demands, General Twiggs did not hound the last of the Seminoles out of the state. Instead, he held a powwow with Chief Billy Bowlegs (also known as Holatter Micco). Bowlegs spoke fluent English. The chief turned over three Indians he claimed were the murderers and the severed hand of a fourth. However, the hapless prisoners insisted they were just scapegoats.

Apparently, General Twiggs believed his captives, because he never did deliver the trio of alleged killers to Ossian Hart for trial (Hart had become the state prosecutor for Florida’s Southern Judicial District with his main office in Key West). Instead, Twiggs allowed his prisoners to ship out to an Indian reservation in Oklahoma Territory.

A monument in St. Lucie Village commemorates the location of Fort Capron, where soldiers tried to bring the settlers back. RICK CRARY

THE LAST HURRAH

In an effort to persuade settlers to repopulate St. Lucie County, the federal government moved in 500 troops and set up a new outpost called Fort Capron in present-day St. Lucie Village, near the scene of the attack. A handful of folks came back, including sickly Caleb Brayton, who served as tax collector, sheriff and mail carrier. His wife finally did come down to share his final days when he was skin and bones. He died on June 9, 1854, when he was almost 38.

With almost no constituents left to represent, 51-year-old William F. Russell took a seat in the Florida legislature, where he served as Speaker of the House from November 1854 to January 1855. During that legislative session, he changed the name of Florida’s first St. Lucie County to Brevard County in honor of a friend in Tallahassee (in 1905 a section of Brevard County was renamed St. Lucie County).

A final clash with the Seminoles began in 1855. Another attempt was made to move them all out West. But in 1858, as the nation blundered toward disunion, the soldiers were called home. They closed Fort Capron and abandoned the area to the natives and their wilderness. The Seminoles

won again.

Memory, like all human possessions, is unequally distributed; and yet, time’s clues are always there to find. Ossian Hart went on to experience more difficult challenges as life moved on. He became a noted Loyalist and opposed Secession when Florida joined the South in the Civil War. During the Reconstruction period that followed, Hart advocated civil rights for Florida’s African-Americans. For a time he served on Florida’s Supreme Court, and then he became Florida’s 10th governor. His term began on January 7, 1873. He had big plans for the New South, but he caught pneumonia early on and never quite regained his health. Governor Hart died in office on March 18, 1874.