PART ONE:

Pioneer Frank Raulerson builds a cattle-ranching empire, but who will take it over?

Rise of a Cattle Baron

The brothers Raulerson arrive early to Fort Pierce and help shape the community while also creating their own successful enterprises

BY GREGORY ENNS

Though his name is vaguely remembered today, Cyrus Franklin Raulerson was once one of the most influential politicians on the Treasure Coast. He also was among its wealthiest citizens.

A pioneer in the cattle industry, Raulerson, known as C.F. or Frank, amassed a small fortune raising cattle and buying land for more than four decades. The Raulerson Building in downtown Fort Pierce, designed by noted architect William Hatcher and built in the1920s boom era, is a testament to his vision and legacy, as is the home he built, impressive for the time, just a few blocks away.

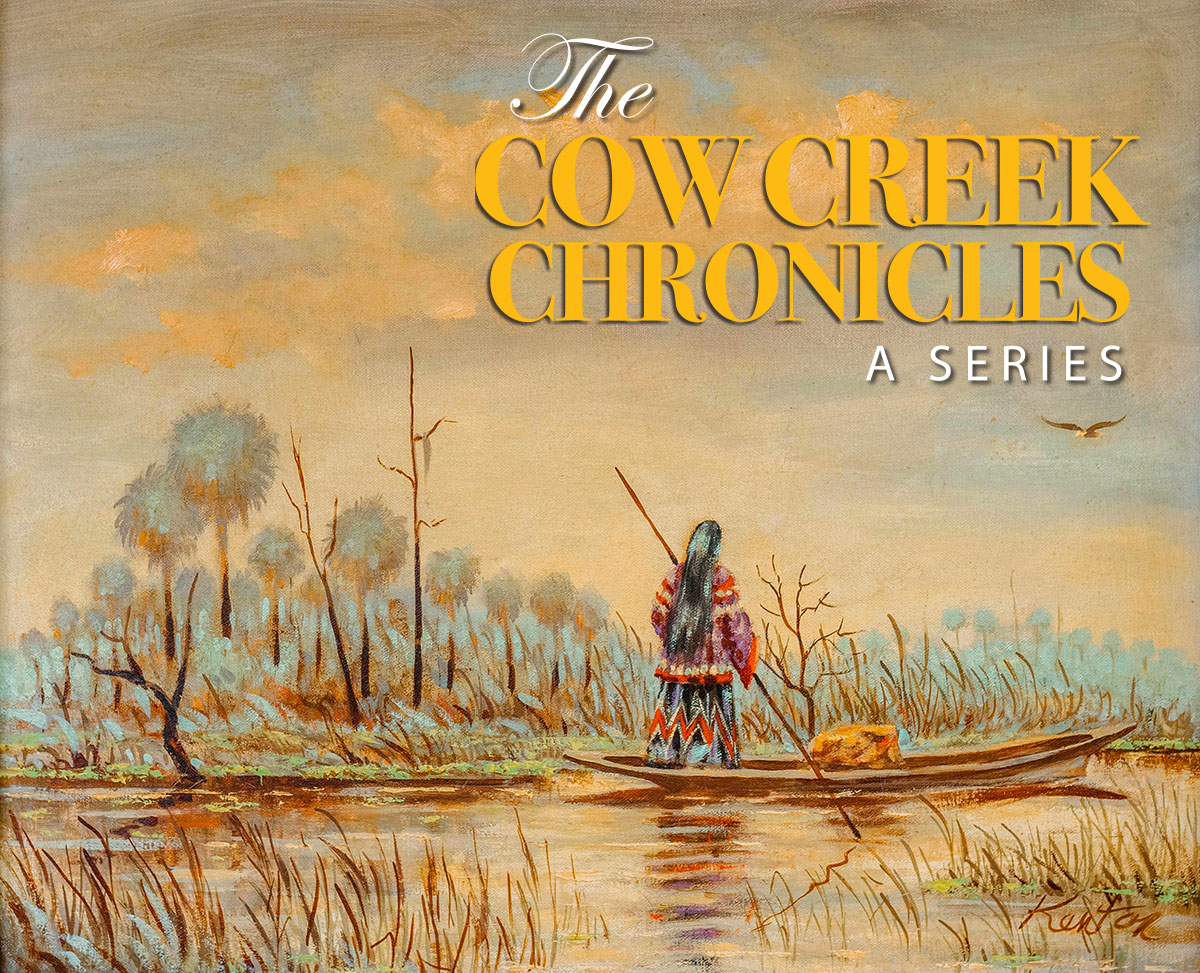

In an era when cattle roamed the open range and interior land was seen as having little value, Raulerson purchased tens of thousands of acres to assemble four cattle ranches, including his home ranch at Cow Creek swamp along the border of St. Lucie and Okeechobee counties.

With his only child, Alfred, working with him in the cattle business in the 1930s, the future of Frank Raulerson's family seemed promising. But Alfred died in a boating accident in 1938, leaving 8-year-old Jo Ann Raulerson, Alfred's only child, as the sole heir to all that Frank Raulerson had amassed.

Believing that they could provide a better life for their granddaughter, Frank and wife, Annie Louise, pressured Jo Ann's mother, Mae, to give them custody of Jo Ann. Mae relented. Although the custody agreement didn't involve a divisive court action, it faintly echoed the national case that played out just four years earlier of "poor little rich girl" Gloria Vanderbilt, who, after the death of her father, was entrusted to her aunt over her mother, who was declared unfit. And like the Vanderbilt case, the Raulerson succession involved a large trust fund.

The story of Frank Raulerson and his descendants is of a pioneering Florida cattle family making its way into the modern age. It is a tale of slow, long-term gains and huge, short-term losses, a story of undying devotion and casual betrayal and ultimately, a story of accepting things the way they are.