Riomar’s humble beginnings

BY BARBARA REID

The year was 1918 and three Midwesterners, Dr. J.P. Sawyer, Dr. W.H. Humiston, and businessman E.E. Strong, were looking for a winter retreat far away from Ohio’s icy-cold winters. Scouring Florida’s east coast for the perfect place to golf, swim and fish, they came across Vero Beach and agreed they had found their little piece of paradise.

The year was 1918 and three Midwesterners, Dr. J.P. Sawyer, Dr. W.H. Humiston, and businessman E.E. Strong, were looking for a winter retreat far away from Ohio’s icy-cold winters. Scouring Florida’s east coast for the perfect place to golf, swim and fish, they came across Vero Beach and agreed they had found their little piece of paradise.

At the time, there were only 70 homesteaders on the town’s mainland and the barrier island was as yet untamed, a mosquito-infested jungle of tangled vines, live oaks and Spanish moss. Snakes inhabited the dense undergrowth and wild boar were said to roam the marshes. To complicate matters even more, there was neither a bridge to access the island nor electricity to light it. But with the Gulf Stream less than 15 miles off the coast, the area experienced lower humidity and cooler evenings than Palm Beach to the south, and together with the lush vegetation and soft ocean breezes, it was exactly what the intrepid explorers had envisioned.

In 1919, the men formed the East View Development Company and purchased a 160-acre tract of land from Lewis Stockel, a settler who owned property between the Indian River and Atlantic Ocean on the barrier island. Enlisting the expertise of noted architect and designer Herbert Strong, they employed barges and mule trains to haul building materials to the site where they constructed a nine-hole golf course stretching 1,500 feet along the coastline. A tennis court, beach club and guest cottage shortly followed, and as word began to spread, a growing community of Cleveland “snowbirds” began building winter cottages within walking distance of the club where they gathered to dine, swim and socialize.

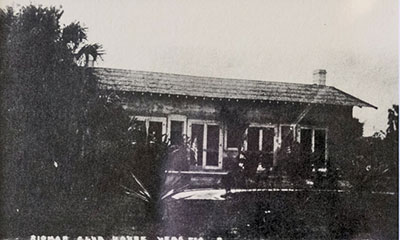

The first clubhouse located on what became known as Ocean Drive. RIOMAR COUNTRY CLUB ARCHIVES

A view of the first few domains purchased on Riomar Drive. RIOMAR COUNTRY CLUB ARCHIVES

Winchester Fitch from New York was among the first members to join the local golf club in 1920 and the first to coin the name “Riomar,” Spanish for “river to sea.” In 1921, his son, George Hopper Fitch, penned a song in which he called Riomar the “Eden of the South,” while his daughter, Dorothy Fitch Peniston, chronicled her recollections of those early days in the book An Island in Time.

Sawyer’s first land purchase covered three lots going all the way from Riomar Drive to Ocean Drive. Here he built his main residence followed by two more homes to accommodate the overflow of family and guests. Seven homes in all were constructed before the little wooden bridge connecting the mainland to the island was built in 1920. According to Peter Coveney and Karen Salsgiver, who wrote a book commemorating the 100-year history of Riomar, many of the original homes were modest affairs with no kitchens. Viewing the short winter season as a social event, members took their meals at the club — an opportunity to catch up on the latest news, share golf scores and schedule cocktail parties.

Many familiar names played pivotal roles in those early years: Entrepreneur and visionary Waldo E. Sexton brokered the 160-acre purchase between Stockel and the East View Development Company for a price of $5,000; Arthur McKee, engineer and co-founder of McKee Jungle Gardens (now McKee Botanical Garden), was the first visitor to occupy the golf club’s guesthouse in 1920 and former Vero Beach mayor, Alex MacWilliam, who helped oversee the construction and management of the golf club, met his wife there in 1920 and bought a home on Riomar Drive in 1924.

Electricity and water came to the island in 1924, and the Riomar Country Club was officially chartered in 1925, boasting the first golf course on the Treasure Coast and the first in Florida to enjoy ocean views. No one was allowed to purchase a Riomar lot until becoming a fully-fledged member of the club, and even then they were carefully vetted, a policy that remained in effect until 1961.

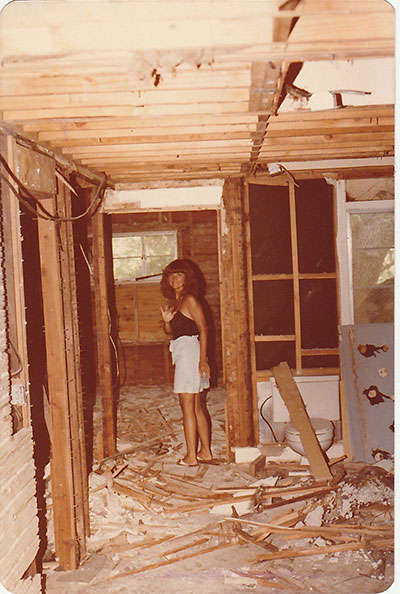

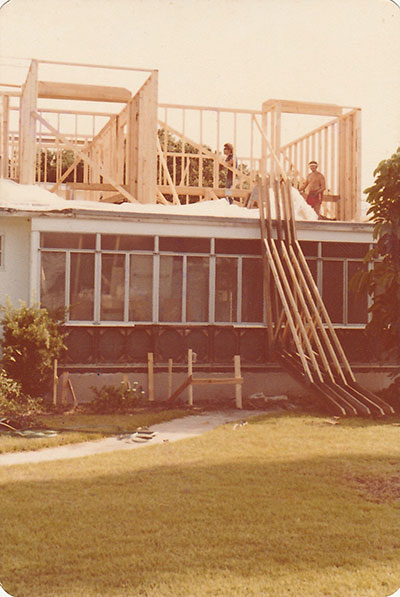

Today, most of the homes built in the 1920s and 1930s have been torn down. Yet the charm that continues to attract residents to the neighborhood is still palpable. Many of the newer homes, nestled in the hammocks of centuries-old oaks, give a nod to the architectural styles of a bygone era. And while the manicured lawns, swaying palms and immaculately trimmed hedges belie the marshy terrain that first greeted the intrepid Cleveland pioneers, the essence of a timeless history still permeates the air.