Never the same

COURTESY OF SKISCIM PHOTOS, ARCHIVE CENTER, IRC MAIN LIBRARY

Wally Skiscim, second serviceman from the right, enjoyed dancing at the USO parties. He returned to Vero Beach after the war to marry Mary Anne Maher.

Wartime had a lasting effect on Vero Beach and its people

BY JANIE GOULD

BY JANIE GOULD

World War II brought permanent changes to the homefront, even to towns as small as Vero Beach in the early 1940s.

The Navy opened an air station at the city airport in 1942 to train pilots to fly dive bombers and night fighters made possible by new radar technology, something Germany’s Luftwaffe was already doing. By the time the airbase closed in 1946, a total of 2,700 officers and enlisted men and 300 WAVES and women Marines had spent time in Vero Beach, nearly equaling the civilian population of 3,000.

Many eventually made the town their permanent home.

At the dawn of the war, the airport was the ninth largest paved facility in the country, author and engineer George Gross wrote in his 2002 book, U.S. Naval Station at Vero Beach during World War II. Originally, it was a refueling stop for Eastern Airlines.

Bump Holman, who operated Sun Aviation at the airport and was a pilot for the Los Angeles Dodgers, said his father, B.L. “Bud” Holman, met the flying ace Eddie Rickenbacker in Detroit after World War I when he was working for General Motors.

“Eddie Rickenbacker, after World War I, came back to Detroit and was involved with Rickenbacker Automobiles,” Bump said in an interview for the WQCS radio oral history project.

Rickenbacker also was launching Miami-based Eastern Airlines. Bud, meanwhile, moved to Vero Beach to launch a Cadillac dealership.

That was in 1925.

Bump wasn’t sure how his father persuaded the airline to come to Vero Beach.

“He knew all these guys, Eastern pilots and executives, and they liked to come here and hunt and fish with him. They said, ‘We need to put a fuel stop somewhere,’ and he said, ‘We’ll put in a fuel stop for you.’ He put in three grass runways, and Eastern operated on the grass runways.”

PAVING THE WAY

Holman’s friendship with Gen. Henry “Hap” Arnold, head of the Army Air Corps, didn’t hurt either.

“They were out hunting and fishing,” Bump said. “The general said, I think he was a colonel then, anyway, he was telling about flying their B-18 bombers around the world to show how powerful we were. My dad said, ‘Well, why don’t you leave from here on your round-the-world trip?’ He said, ‘We’ve got to have paved runways,’ and my dad said, ‘Yes, I know.’ ‘Why don’t you pave some runways?’ So he did.”

Holman said everyone expected the Army Air Corps to get the airbase.

“All of a sudden, the Navy flew into town one night and the next day they had it!” he said.

The training was extremely hazardous, especially in the early years when pilots were learning to fly dive bombers.

“They had terrible airplanes,” Bump said. “They lost eight of them in the city limits in one night. The main target was out at Blue Cypress Lake. They had a target right in the middle of the lake, so they had a hell of a time fishing pilots out of the lake. “

Sig Lysne, one of the first dive bombers to be trained in Vero, remembers seeing targets drawn on rafts in the lake. In Gross’ book, Lysne said pilots would ascend to 10,000 feet before heading toward the target at a 70 degree angle, and a speed of 300 miles per hour.

“You’d start to pull out at about 1,500 feet,” he said. “If you waited any longer, you were flirting with the ground.”

NIGHTTIME FLYING ANTICS

Later, with the advent of radar, the Navy started training pilots in night-fighting aircraft. Pilots in Vero often flew east over the Bahamas at night to practice with instruments.

“They had pretty experienced pilots so you didn’t have near as many accidents,” Bump said. “We lived two or three blocks south of the airport. You could hear those engines running out there all night. Every once in a while one of them would taxi up on another and you’d hear chop-chop-chop. They’d chop the tail off them.”

Suzan Phillips, longtime local resident, was living with her parents in their beachfront home in Riomar. She remembers pilots buzzing their home as they flew back to the air station in the newly produced Grumman F7F aircraft.

“These boys went out at night and they came back at 4 o’clock in the morning right over our house because I knew a couple of them,” she said in a radio interview. “My father would get furious! He’d wake up and stand on the balcony and shake his fist and try to get the number off the plane so he could call the base and say you’ve got to go tell those guys they can’t do that! They thought it was great fun, and later on we’d all get together at the Bucket of Blood (Ocean Grill) and laugh about it.”

ACCIDENTS TOOK THEIR TOLL

A total of 105 pilots were killed during training in Vero Beach during the war, Gross said, mostly from the Navy and Marine Corps but also two from the British Royal Navy Air. Nearly every week, the Vero Beach Press Journal reported crashes and deaths, according to Otis G. Pike, a pilot who became a lawyer, represented New York in Congress and then retired to Vero Beach.

“We were young, very proud, very daring and much too foolish, for behind the headlines senior officers wrote cruel assessments that usually blamed the deaths of one or two more people on pilot error,” he wrote in the foreward to Gross’ book.

Eastern Airlines co-existed with the Navy during the war. The airline continued to fly in and out of Vero from the edge of the airbase.

“I think my dad just talked the Navy into letting them do it, and talked Eastern into continuing to come here,” Bump said. “I guess one hand washed the other. Eastern built the hangar here in the early 1930s. When the war started it was right in the way of the Navy, so they moved the whole hangar. Then, after the war, they moved it back. They took it apart and put it back together twice.”

Historian and author Gary Mormino wrote in his 2005 book, Land of Sunshine, State of Dreams: A Social History of Modern Florida, that the war effort exposed Florida’s charms to thousands of military people who had never been far from home. The state had a network of military training centers from the Panhandle to Key West.

“Never had so many impressionable young adults visited Florida than in the years 1940-45,” Mormino wrote.

TOURISM FLOURISHED

Florida was so awash in soldiers, sailors and airmen that The New York Times, on Nov. 15, 1942, ran a story stating that even though 40 percent of the Sunshine State’s hotels were occupied by military personnel, lodging was still available for civilian visitors. The notion that Florida would be dead during the tourist season was false, the Times insisted.

“Florida will be as much alive as servicemen on leave and war workers, with money in their pockets to jingle-jangle-jingle, can make her,” the Times said.

McKee Jungle Gardens in Vero Beach and other attractions around Florida offered reduced rates to men and women in uniform.

Generations of bored teenagers in Vero have slammed their hometown as Zero Beach and sometimes embellish the slogan, “Where the tropics begin,” with the phrase “…and civilization ends.” Gross said it all started with military people who grumbled about the town’s small size and dearth of nighttime entertainment.

But like Pike, many of the pilots who trained in Vero Beach later made the town their permanent home. James Curzon was a Marine Corps pilot out of Pensacola when he was sent to Vero Beach to train in dive bombers.

FRIENDLY FOLKS

In a radio interview, Curzon talked about the friendliness of local folks, who often let him hunt on their property and even in their citrus groves, as long as he didn’t shoot into the trees. Pellets would cause the fruit to rot.

“I never worried about being lost or being without, knowing that if I asked for something it would either be given to me or I would be helped or shown a way to get it,” he said.

Curzon and his buddies liked to go shrimping at the old Winter Beach Bridge.

“When the shrimp got running, you could sit there and fill one of those big coolers with shrimp, and I mean good-size shrimp, in a couple of hours,” he said.

Cooks in the mess hall would boil the shrimp and “we’d sit there, eat shrimp, drink beer and have a good time,” he said.

He also enjoyed airboat fishing for big-mouthed bass in swamps that started just a couple of miles west of town and extended to State Road 60’s 20-Mile Bend.

Curzon’s parents were so taken with the area after visiting one winter that when they returned home to Illinois to face a blizzard, they came back and bought a grove. Curzon settled in Vero Beach after leaving the Marine Corps in 1958. He worked as a pilot for the Dodgers, had a business with Mickey Mantle and served as the county’s property appraiser.

AROUND THE TOWN

Sailors strolled the streets of Vero Beach during the war years and danced with local girls at USO dances in the community center. Musicians at the airbase formed a dance band to provide live entertainment in town. The Navy sponsored beach parties and handed out life rafts for Navy personnel to practice on in case they ever had to do an emergency landing.

The biggest party undoubtedly was the celebration when the war ended. Hilda Harbourt viewed the throngs of people who came from the air station to celebrate. She had a front row seat from her desk at the Western Union telegraph office on 14th Avenue, but didn’t join the festivities.

“I was working!” she said.

During the war years, townspeople also caught sight occasionally of military personnel from neighboring bases. The Navy’s Underwater Demolition Teams, predecessors of the Navy SEALs, trained on Fort Pierce beaches.

Sometimes, they conducted mock raids of the air station. Their task was to get from the beach to the captain’s office at the airbase without being detected.

Bud Holman used to stop by the captain’s office every morning for coffee, Bump Holman said. No one ever searched his car before letting him pass through the gate. One morning, he was driving through the McAnsh Park neighborhood just south of the airbase.

“He sees two of those Navy SEALs out there, all in camouflage and guns and everything,” Bump said. “He waved them over and said, ‘Hey, you want to catch the commanding officer?’ He put them in his trunk and drove into the base and right into the captain’s garage.

He went in and sat down and was having coffee with the captain. All of a sudden, these two guys walked in and they had him!”

CLOSE TO HOME

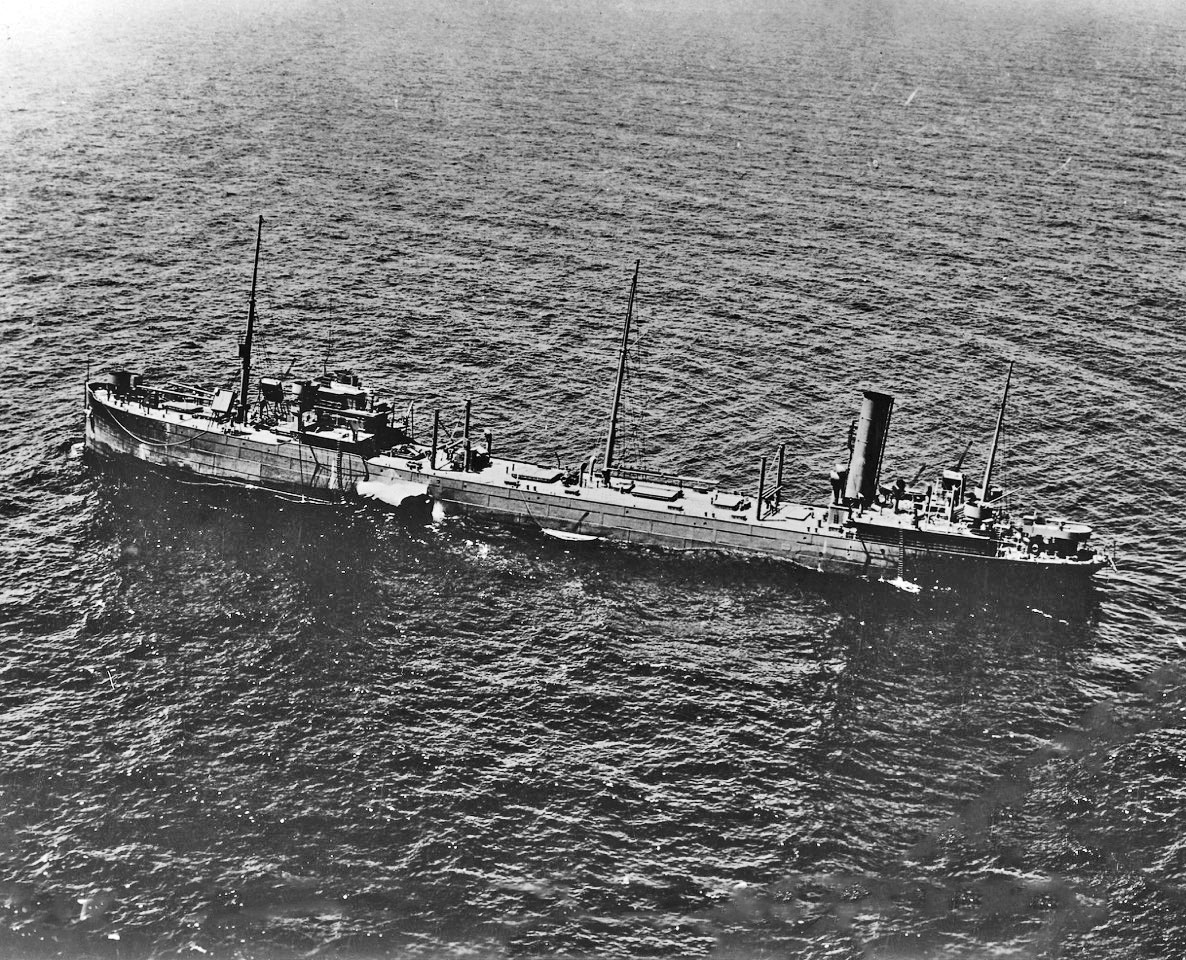

German submarines prowled offshore during the early years of the war, wreaking havoc on shipping in the Atlantic, the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico.

Longtime residents of the Treasure Coast have never forgotten torpedo blasts from U-boats that sank freighters and shook the ground for miles around. One blast off Jupiter Island in 1942 rattled the chips in a poker game in a Stuart law office 15 miles away.

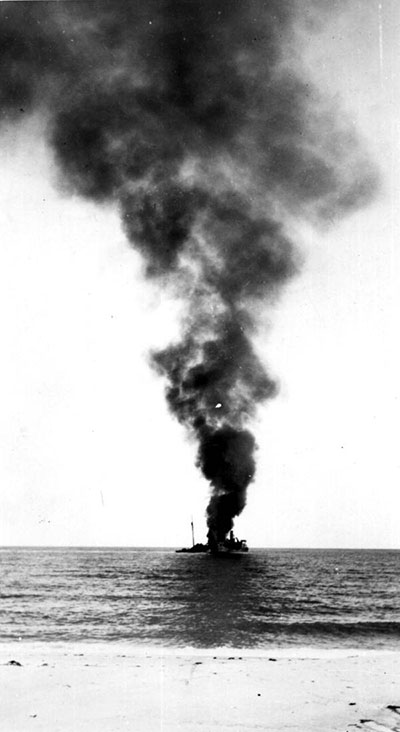

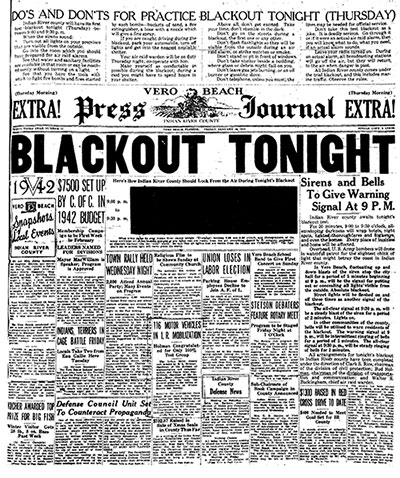

The war struck Vero Beach in the dark, early hours of May 6, 1942. A German submarine, U-333, torpedoed the U.S. oil tanker Java Arrow eight miles off the beach. The explosions rattled windows in town. Coast Guard volunteers from Vero in Kit Johnson’s 33-foot fishing boat rescued 22 survivors, some wounded, and took them into the Ft. Pierce Coast Guard Station. Before dawn a few miles to the south the U-boat sank a Dutch freighter, Amazone, and another huge tanker, Halsey. Giant plumes of smoke were seen from Vero’s beach as the Halsey burned.

The U-boat commander Peter Cremer later stated, “Those Americans did not know they were at war.” He had seen a coastline with an array of lights, silhouetting the ships. Ten days after his attacks the government imposed a blackout on Vero and other coastal towns. German U-boats sank 24 ships in Florida waters in 1942.

Vero Beach resident Harry Hurst grew up in Winter Beach during the war and remembers that the Coast Guard patrolled local beaches, initially on foot. His father, too old to serve in the war, volunteered to transport Coast Guardsmen to and from their observation posts in his truck.

Eventually, the Coast Guard acquired horses so the men could patrol on horseback, which allowed them to cover more territory in less time. Hurst wasn’t allowed to tag along, but remembers seeing some of the herd in a stable near Wabasso beach.

“These were not old mules,” he said. “They were nice looking horses.”

LOCAL WAR EFFORT

Many residents volunteered to serve as spotters at observation posts on the beach. They scanned the ocean at night, looking for signs of U-boats. Armed with binoculars and plenty of coffee, Phillips did all-night duty atop Vero Beach’s tracking station, now the site of a public beach and park.

“It was scary at night and it was very dark,” she said. “You’d see these tiny little lights and it was worrisome. You weren’t supposed to be seeing those! We never saw anything that really made us call the person in charge. The lights told us they were out there but we never really saw them that close.”

Hurst aided the war effort when he was a sixth-grader at the Winter Beach School. The teacher put up a large photo of an Army jeep, with parts labeled and a price for each. The children would bring in their dimes and quarters and after several months would have raised enough to buy an $18.75 war bond. The principal, Meta Chesser, would take the class to the Indian River Citrus Bank in Vero Beach.

“They had a bell and tower there, so we’d exchange the book of stamps for a war savings bond and someone would ring the victory bell,” Hurst said.

Air-raid drills and rationing were facts of life during the war years.

JJ Wilson, a seasonal resident, lives in her family’s historical Riomar cottage, which still lacks air conditioning and heat. She first visited in the early 1940s, when her family came down from Northern Virginia for the winter. It was wartime, which meant gas and Scotch whiskey were in short supply.

“Rationing meant we didn’t drive down because we didn’t have gas,” she said. “We took the train.”

NIGHTLY AIR- RAID DRILLS

She remembers air-raid drills at night, when her family was required to turn off the lights and get away from the 71 windows in the house.

“Where the bar is now was a closet,” she said. “It was the only place without windows, so we would all go in there, at 8 o’clock I think it was, and hang out there until the all-clear sounded. Since it was a bar, the adults had a few drinks and got jollier and jollier.”

Scotch whiskey was nearly impossible to get, and Wilson said her mother bought from a merchant who required customers to buy six bottles of rum to be allowed to purchase one bottle of Scotch. Once, her mother had squeezed a load of grapefruit to make juice to mix with rum for a party. Wilson and her playmates, meanwhile, were spending too much time in the sun.

“We went to where the club is now, the fancy Quail Club,” she said. “It used to be an oyster bar. We played on it for so long that we got sunstroke. When we got back we drank all the grapefruit juice that was ready for the party.”

A doctor who treated the kids said they were so dehydrated that the juice probably saved their lives.

Curiously, Florida grapefruit juice was in short supply in most of the country during the war. Florida shipped canned grapefruit juice to service members overseas. Ads claimed the juice was loaded with “Victory Vitamin C” essential to the war effort.

“How good to know that our boys chasing Adolph’s ‘supermen’ are armed with Victory Vitamin C,” an ad from the Florida Citrus Commission proclaimed.

AFTER THE WAR

AFTER THE WAR

The Naval Air Station was decommissioned in 1946 and the property returned to the city. Some of the buildings became the core of Dodgertown, the spring-training facility of the Brooklyn, later Los Angeles Dodgers. The Navy dispensary served as the city’s hospital until a newer facility was built in the mid-1950s. Navy barracks became the Airbase Apartments, providing inexpensive units for young families when housing was in short supply .

The Vero Beach Regional Airport became the hub of a commercial and industrial park anchored by Piper Aircraft. Eastern Airlines is long gone, but Elite Airways provides regularly scheduled commercial service. A historical marker at the airport lists the names, ranks and service branches of all who died while training for war in Vero Beach.

Commercial fisherman and guide Richard Milton Jones served in the Army as part of the Allied North Africa invasion. Afterward, when he returned to his family’s historical home on Jungle Trail, he faced more fighting men.

He says about 200 men from the Navy’s Underwater Demolition Teams , along with some Army Scouts and Raiders, were marching north from their base in Fort Pierce when they passed his house en route to Sebastian Inlet.

“The mosquitoes were chewing them a good one!” he said. “They marched up to Sebastian Inlet before A1A was even thought about, and when they got there they made a bivouac. They had all their foodstuff and they had a lot of demolition stuff.”

Jones said they hoped to get rid of the explosives while also reopening the inlet, which was filled up with sand.

“They put the TNT they had in hoses, long hoses, and they dug a trench across the mouth of the inlet and they put it down in there and covered it up,” he said. “They were going to blast the inlet open! That was a foolish idea. They blew it straight up in the air and it came right back down the same hole it blew from. But they got rid of the TNT. That was the object.”

The mosquito-plagued men stayed at the inlet for a couple of days before abandoning camp and leaving everything they had brought. Jones got wind of that and managed to salvage some of the gear.

“I had this beach buggy and me and this friend of mine discovered what was up there,” he said. “We met this contingent of men marching on the beach going back to Fort Pierce. A captain was in charge. I stopped and said, ‘Captain, we’ve been up there and looked over your bivouac and there’s lot of good food up there. There’s a lot of lifesaving equipment, all kinds of tools, silverware, baloney, sausage, milk. Everything!’ I said, ‘Have you left that stuff behind up there?’ He said, ‘Yeah, we ain’t coming back.’ I said, ‘Would you give it to me?’ He said, ‘I won’t see you if you get it.’ ”

Jones and his buddy made two round trips with their fully packed beach buggy.

“When we went back the third time to get the third load, we had a competitor! He had an old Model-T and he was up there picking up stuff, so we traded.”

Jones, a third-generation native, died in 2011 at the age of 92. He sold the family’s property, which includes the iconic Jones Pier on the Indian River Lagoon, to the county for use as a public preserve and historical site.

Rudy Johnson contributed to this story.