My Family’s Journey to America

Indian River Magazine Publisher Gregory Enns shares the story of his Russian Mennonite family’s journey to America

BY GREGORY ENNS

We all have questions about our family history. In childhood, I only gathered bits and pieces about my father’s family from what I heard from my dad or my paternal grandfather, E.R. “Putz’’ Enns, who arrived on what we now call the Treasure Coast exactly a century ago.

From my grandfather, I knew that he arrived in Florida with his uncles Paul and Nick from Inman, Kansas, in 1923. I knew that the family had a flour mill in Inman, where he worked as a boy, and that his father had died when he was an infant. I knew that the family was Mennonite and spoke German, though they had come to the United States from Russia. And finally, I was told that the family’s modern origins probably began in Austria either in the village of Enns or along the River Enns valley.

Luckily, my early relatives knew how to get their names in their small-town newspapers, so I had a pretty good record dating from the 1890s about their comings and goings. At least two of the relatives — including one who was a newspaper editor — were pretty good writers and left reminiscences about our family’s journey. I also had earlier research on the family from my aunt Susan Enns Stans, a Ph.D. anthropologist, to rely on in reporting this story.

JOURNEY TO AMERICA

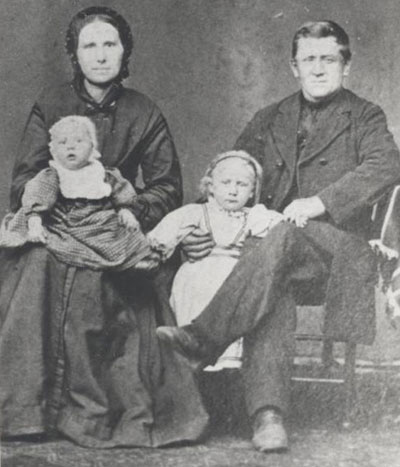

After a trans-Atlantic ocean voyage, my branch of the Enns family arrived in the United States in 1879, hitting their destination of Kansas on July Fourth.

Stepping off the train were my great-great grandparents Cornelius Enns (1839-1905) and Elizabeth Martens Enns (1843-1936), accompanied by their six sons, one of them an infant.

One of the boys, Heinrich, 70 years later would recall the family’s voyage and their reason for coming to America.

“When near the age of ten, my father and mother, then in the prime of life, were forced to make a momentous decision,’’ Heinrich, who became known as Henry, wrote in a letter to his three children in August 1950. “They lived and had their being in Gnadenfeld, South Russia (Ukraine) and the year of 1879 was the closing year for unmolested immigration to other lands on the part of the Mennonites, who originally settled on the steppes of Russia.’’

Uncle Henry said in his letter that Peter the Great (1672-1725) had invited the Mennonites to Russia, but it was actually his granddaughter-in-law, Catherine the Great (1729-1796), who did the inviting.

The Mennonites and Russia had friendly relations going back to the days of Peter the Great, who reportedly spent a week with Mennonites and visited a Mennonite church during a stay in Amsterdam and who recruited a Mennonite to become his personal physician in Russia. Catherine, a German princess, became czarina 37 years after Peter the Great’s death when troops loyal to her overthrew her husband, Peter III, grandson of Peter the Great, as czar.

GUARANTEES OF FREEDOM

As czarina from 1762-1797, Catherine was in possession of large tracts of virgin land along the Volga River. To populate the region and turn it into productive agricultural land and create a barrier against nomadic Asiatic tribes, Catherine issued a manifesto in 1763 inviting German immigrants to farm the Volga land and later Ukrainian lands north of the Black Sea that had been acquired from Turkey.

The manifesto guaranteed freedom of worship, establishment of schools in the German language and exemption from military service. Specifically, the Mennonites from West Prussia would be guaranteed freedom “for all time’’ and 165 acres of farm land to each family.

The offer prompted a mass migration to South Russia, and the guarantees allowed them to develop as an insular colony, retaining their low-German dialect, Plautdietsch, which had developed in their days in Prussia. They were able to have control of their churches and oversee the schools of their children, which held classes in German instead of Russian and included studies on their Mennonite faith. They also ran their own local governments with little outside interference from the Russian state.

The Enns family’s time in Russia went back at least two generations before the birth of Cornelius Enns there in 1839. The generations included Cornelius’ father, also named Cornelius (1816-1883) and born in South Russia, and his grandfather, also named Cornelius (1788-1826), who moved to Fuerstenau, South Russia, in 1812.

Like many Russian Mennonites, the Ennses were wheat farmers. They were also prolific. The first Cornelius Enns was the father of nine children who survived to adulthood, the second Cornelius was the father of 13, and the third Cornelius, my great grandfather who would emigrate to the United States, was the father of nine sons who would spread the name in America.

ENNS ORIGINS

The villages in which the Ennses lived in Russia were part of the Molotschna Colony, now known as Zaporizhzhia Oblast in Ukraine. Molotschna consisted of 57 villages and was the second largest Mennonite settlement in the Russian Empire, reaching a population of about 40,000 by 1869. At Molotschna, each village elected a magistrate who oversaw village affairs.

Exactly where or when the Ennses had emigrated to Russia before 1812 is unknown. Family histories show that the father and grandfather of Elizabeth Martens (1843-1936), who emigrated to the United States with husband, Cornelius, came from the Vistula River delta in West Prussia (Danzig, Poland), where Mennonites from The Netherlands and present-day north Germany settled in the mid-1500s.

It’s likely that the Ennses came there as well, since the Molotschna Colony in which they live was founded by West Prussian Mennonites. Polish King Wlaldislaw IV had invited the Mennonites to live along the Vistula River delta and farm the land. Building dikes, the master farmer Mennonites turned the marshy ground into productive agricultural ground.

But when Poland became part of West Prussia, [modern Poland], Frederick William II imposed heavy fees on the Mennonites for their military exemption and limited their access to additional land because of their resistance to paying them. Since the Mennonites were traditionally farmers with large families, limiting access to additional land forced younger generations to seek occupations other than farming. Thus, Catherine the Great’s offer of free land and the ability to practice their religion and enjoy the military exemption without tax was highly appealing, prompting many Mennonites to accept her invitation.

The Enns family presumably originated from the town of Enns, Austria’s oldest city and located on the Enns River. With Austria under the Catholic Hapsburgs who fought the Reformation beginning in 1517, many Lutherans and Anabaptists such as Mennonites fled or were expelled from Austria. The name has a number of variations, including Ensz and Ens.

FAITH’S FOUNDATION

Mennonites trace their beginnings to the so-called Swiss Brethren, Anabaptists who formed near Zurich in 1521 as part of the Protestant Reformation that split from the Catholic Church. The religion is named for Dutch priest Menno Simons (1496-1591), an early leader of the Anabaptist movement, which espoused voluntary adult baptism, a practice heretical to the Catholic Church at the time.

Other precepts included close adherence to the Bible and teachings of Jesus and a refusal to take oaths. Early Mennonites were also strict pacifists, believing that conflict can be avoided by other means than war.

The Mennonites and the better-known Amish have similar belief systems, though they differ in how they practice those beliefs. Mennonites are open to modern technology like the use of electricity, automobiles and telephone. The Amish, whose founding is attributed to Jakob Ammann, a Mennonite elder, are known for their traditional dress, with women wearing bonnets and plain dresses. Men also wear solid colors with suspenders and black or straw broad-brimmed hats. Married Amish men often have beards without mustaches. The beard signifies that they are married and the lack of a mustache became a convention in the 17th century, when many European countries required men in the military to wear mustaches.

The two religions also vary in their approach toward education. Many traditional Amish believe that formal education isn’t needed past the eighth grade, with vocational training sufficient for success later. But Mennonites are more open to advanced education, and six colleges in the United States are affiliated with the Mennonite Church.

LIFE IN RUSSIA

In Russia, the Cornelius Enns who would immigrate to America grew up in Landskrone, founded in 1839 by Mennonite settlers from West Prussia. In Landskrone, his father had an old fashioned treadmill, where Cornelius learned the milling trade.

The Ennses grew Turkey Red, a hearty drought-resistant wheat that could be grown in winter. A so-called hard wheat, Turkey Red gained widespread use by Russian Mennonites like the Ennses living on the former Ukrainian lands.

MILLER MARRIES

At age 22, Cornelius married Elizabeth Martens, 16, daughter of Aganeta Thiessen and Abraham Martens, who owned an orchard in Landskrone. Elizabeth had been entered into the Mennonite church of Morgenau in Gnadenfeld. Cornelius also had been baptized into the Mennonite church.

Shortly after his marriage, Cornelius bought a windmill seven miles away in Gnadenfeld. When a hurricane destroyed the windmill, he rebuilt it, placing it in a more favorable location.

The young family lived on a 165-acre farm in Gnadenfeld that Cornelius had purchased. The main house consisted of a brick white-washed structure and thatched roof and had a brick stable and barn attached.

In Gnadenfeld, Elizabeth gave birth to nine children, six of whom survived infancy: Cornelius, born in 1862; Abraham Cornelius, my great grandfather, born in 1865; Hermann, born in 1867; Heinrich Thiessen (Henry), born in 1869; Dietrich (Dick), born in 1876, and Johann, born in 1878.

The move to nearby Gnadenfeld, translated as “grace field,’’ helped distinguish Cornelius from his siblings. Boasting higher-level schools and as the seat of the government volost, or circuit, Gnadenfeld was a progressive village, and Cornelius served as its vice mayor. In some ways, he was following in the footsteps of his father, who had served as mayor of Landskrone.

RUSSIAN SCHOOL LIFE

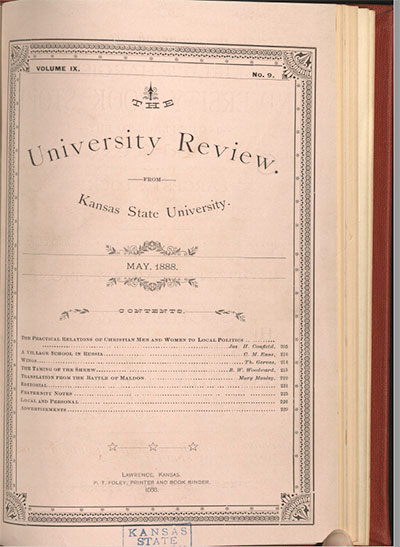

Cornelius Martens Enns, Cornelius’ second son, recalled going to school in Gnadenfeld in an article appearing in the May 1888 Kansas Review entitled A Village School in Russia. The younger Cornelius, who went by C.M. Enns in his writings, was attending law school at the time, and fondly recalled those halcyon days in Russia.

He wrote that his Mennonite school was an enormous brick whitewashed building with huge double doors at the front topped off with a thatched roof and a huge chimney billowing black smoke in the winter. As spring arrived, stately poplars shaded the sidewalks, while birds sang atop the trees and girls scurried in the playground below.

The hero of his essay was his schoolmaster, Dirks, “a tall, stately gentleman, with a noble face’’ who had taught at the village school for more than 15 years. C.M. said his large classroom accommodated more than 100 students and had as its most prominent features a large pulpit at the front of the room and an eight-foot-high brick heater near the door that was fed with wood straw or dung by a servant in the next room. The room was positioned with a long line of desks with the boys on one side and the girls on the other.

C.M. said his first book in the Russian school was a German primer, with the New and Old testaments in German as their readers. He said Dirks would reward achievement with a picture of Jesus and the apostles. “As German was the language of instruction in most other branches, we generally spoke a good high German at the end of our elementary course of seven or eight years,’’ he wrote.

ADDITIONAL STUDIES

He said students began the study of the Russian language at 8 or 9. Arithmetic was done on slates, with mathematical equations on 150 charts.

Students also studied biblical and church history. Bible verses were recited twice a week and long hymns and long answers in the Mennonite catechisms were recited every Friday afternoon. Singing led by Dirks, described as one of the best singers in the German settlement, was done from religious hymnals. Wrote C.M.: “Our master planted in our minds a profound reverence and worship of the Great Founder of Christianity, and acquainted us with the vicissitudes and glorious victories of the church.’’

Also on Fridays, C.M. said Dirks would read histories to the students of Peter the Great and his nobles and stories about Germany, France, England and Scandinavia.

Corporal punishment was practiced at the school, C.M. wrote, with only the boys being struck. C.M. confessed to receiving “my moderate portion with a great deal of feeling, and a number of interjections expressive of deepest sorrow and distress.’’

C.M. also shared a school-boy crush. “On Sundays, while the minister spoke about the total depravity of the human heart, my eyes would wander over to the other side and admire the modest, angelic beauty of Lieschen, the fair daughter of the village innkeeper. But in spite of all this, an inexplicable feeling of awe and distrust seized me every time I was brought face to face with the dreadful reality of living girls.’’ Girls, he wrote, “were the great mystery and the great unknowable of my school life.’’

FAVORED SPOTS

C.M.’s brother Henry, in his 1950 letter, wrote that as the family prepared to leave Russia in 1879 C.M. had graduated from the gymnasium, or college preparatory school, in Gnadenfeld, and second-oldest brother Abraham Cornelius had completed his first year. And while classes were conducted in German with Russian a mere class, Henry recalled that students had to sing the Russian national anthem every day.

For recreation, one of the boys’ favorite spots was a clear-water swimming hole harnessed by a dam on the Kurudushan River in Gnadenfeld. Another favorite spot was the nearby East Waldwehr Forest, where “the trees were tall and majestic to climb for play,’’ Henry wrote.

Henry said his father’s mill took in wheat to exchange for flour. He said his father would take the excess wheat by horse wagonload to Berdiansk, a seaport on the Sea of Azov. The wagon would travel down a treacherous road that required placing what Henry called a sled brake under the right wheel, which prevented the wagon from sliding down the hill.

“The Mennonite settlements prospered, changed the barren steppes to an agricultural paradise and with it all, enjoyed full and complete Home Rule, as it were in religion, education and politics,’’ Henry wrote.

WINDS OF CHANGE

For the Enns family and other Mennonites, life was good for nearly a century in their insular colonies, and they were able to retain their cultural practices without assimilating with Russians.

But the guarantees granted by Catherine and her successor, Paul, were revoked by Czar Alexander II in1871. He gave the Mennonites and other immigrant colonies until the close of the decade to adapt to Russian customs, including eligible males to register for the military or tree service, or leave.

In their century in Russia, the Mennonites had prospered beyond all expectations, gaining far better economic status than the former Russian serfs and creating a political problem for the czar. The Mennonites had also essentially accomplished what Alexander II’s predecessors wanted by settling the lands while easing the country’s food crisis.

With Alexander II’s removal of the military exemption, many Russian Mennonites began planning their move.

But where to go?

In 1872, former colonist Ludwig Bette returned to South Russia for a visit after leading a party of 83 people 23 years earlier from the Black Sea to the United States, settling in Ohio. Bette extolled the freedoms and opportunities in the United States, and word spread.

In the United States, Russian Mennonites and other immigrants could also take advantage of the Homestead Act of 1862, which granted free federal land to heads of households over 21 after five years of living on it. The offer was made even to foreigners as long as they agreed to become U.S. citizens. Some Mennonite communities declined to take advantage of the Homestead Act, fearing that the land transaction with the U.S. government would require them to serve in the military in the future.

KANSAS BOUND

Why did many Russian Mennonites choose Kansas as their destination?

After the Atchison Topeka and Santa Fe Railway completed its tracks to Colorado in 1872, the railway offered land in Kansas at $2.50 an acre. At the same time, German immigrant C.B. Schmidt, who was selling farming equipment in Lawrence, Kansas, was corresponding with German-language newspapers in South Russia, extolling the virtues of Kansas and its farming opportunities. Schmidt also heavily emphasized an 1865 Kansas law that exempted conscientious objectors in the state from military service without requiring a tax. A mass immigration of Russian Mennonites to Kansas was on.

The first Enns in my family’s line to emigrate from Russia to the United States was Cornelius’ brother, Dietrich Enns, who settled in Kansas in 1874.

Dietrich, who would establish a farm northwest of Burton, Kansas, and later run a furniture store in Inman, arrived with the first wave of Russian Mennonites to Kansas.

In 1873, a delegation of 12 Mennonites toured Kansas and Manitoba, Canada. Four of the conservative delegates chose Manitoba for future immigration while eight liberal delegates selected Kansas. Between 1874 and 1880, some 10,000 Russian Mennonites left for the United States while 8,000 left for Manitoba. Thus, the first Ennses arriving in America settled in both Kansas and Manitoba. And because of the multiple children over multiple generations, there were many different branches of the family. I only relate here the voyage of my small branch.

ENTICING DESCRIPTIONS

Dietrich’s descriptions of the opportunities in Kansas in letters back home were enough to prompt action from his brother. In 1879, with less than a year before his six sons would face the prospect of military service and five years after Dietrich left Russia, Cornelius put in motion his family’s departure for the United States.

Henry Enns wrote in his letter that his parents decided to sell their flour mill, farm and other belongings “and move from the steppes of Russia to the prairies of Kansas.’’ Oldest brother Cornelius, in notes written in 1937, said his father sold the “farm buildings, village lot with buildings, trees, orchard and garden within village of Gnadenfeld, and fields and pasture outside of village for about 3,000 rubles, prices being low on account of emigration to U.S.’’ The 3,000 rubles translate to about $65,000 today.

The family of eight left by rail to Antwerp, Belgium, where they stayed for three days before boarding the steamship SS Switzerland. Henry did not say in his letter whether the family carried Turkey Red hard winter wheat seed with them.

ARRIVAL IN AMERICA

Henry said the voyage took 14 days in rough seas, with most family members getting sick except him and his older brother, Cornelius, who was absorbed in studying English.

After traveling 98 miles through the Delaware River from the Atlantic, the steamship arrived in Philadelphia on June 24, 1879. There the family boarded a train. “We were all weary and tired, sleeping in full harmony to the click of the train on solid ground, instead of being on ship with billowy movements over watery depths,’’ Henry wrote.

They arrived at their destination of Burton, Kansas, on July 4, 1879. As they stepped down from their Santa Fe Railway car, Henry said he heard tremendous noise and feared it was an Indian raiding party. Luckily, Dietrich Enns was waiting for them and cleared things up. “[It] made us rejoice to the idea of landing in the Land of the Free on the greatest day in U.S. history, July the 4th.’’

The family then boarded farm wagons and made the 15-mile trek to Dietrich’s farm northwest of Burton. “The night was clear, the stars above shone bright and not even the moaning wolf call of the then-common prairie coyote disturbed the slumbers of our content.’’

BUYING THE FARM

As they settled in over the next few days, Cornelius learned about 160 acres in McPherson County that were being sold by Iowa settler Charles Schweer who arrived just two years before. Apparently the land was too difficult to farm. “He came to Kansas displaying the sign Kansas or Bust and was ready to go back to Iowa with the sign upside down,’’ Henry wrote.

Cornelius was able to purchase the partially improved farm for $1,600 or $10 an acre, a price that included a wagon, team of horses and necessary farm implements. Henry said his father also purchased a team of trained oxen.

“Our pioneer settlement became a growing concern, in line with thousands of other settlers before us and many that came later,’’ Henry wrote.

The Enns family initially raised feeder cattle on the farm, grew wheat and was known for selling bread out of their house. It would take Cornelius 15 years before he’d return to the milling business.

AMBER WAVES OF GRAIN

The wheat grown at the Enns farmstead was undoubtedly Turkey Red, though Henry never said in his letter whether the family had brought Turkey Red wheat seed with them from Russia.

Turkey Red was introduced to America by Bernhard Warkentin (1847-1908), a Mennonite from Crimea. Warkentin had settled briefly in Summerfield, Illinois, before moving to Halstead, Kansas, in 1873 with other Mennonites and building the area’s first grist mill.

Warkentin was instrumental in persuading Kansas farmers to switch from growing soft spring wheat into growing hard winter wheat, which was more suited to the Kansas climate and could be easily handled in his steel roller mills. Spring wheat, which grew during the summer, was more susceptible to drought and dying in the hot sun. The hard winter wheat, which is sown in the fall and harvested in the summer, also has a higher protein content than soft spring wheat.

Turkey Red became central to American wheat farming and was a major contributor to Kansas becoming the breadbasket of America.

CHURCH AND MORE CHILDREN

Shortly after their arrival in Kansas, the family joined the nearby Hoffnungsau Mennonite Church, founded in 1875 by Russian Mennonites from the Molotschna colony from which the Ennses came.

In addition to their six boys born in Russia, Cornelius and Elizabeth had three more born in Kansas: Jacob in 1882, Paul in 1885, and Nickolai in 1890. Two other children, born in 1881 and 1887, died in infancy.

Though the family’s early years in America were trying, Henry said they were also satisfying. “The community spirit of cooperation among the settlers seemed God-inspired, and the helping hand was always out-stretched,’’ he wrote. “There was plenty of work for all in season, but also compensating days for hunting, fishing and best of all, barn dancing and other community affairs of church and school.’’

In some ways, the community spirit they enjoyed in Russia was transplanted to Kansas. Many branches of the Enns family, close and distant, settled in neighboring Kansas towns. Besides Cornelius’ brother Dietrich in 1874, youngest brother Peter W. Enns also emigrated to Kansas from Russia.

Peter’s mother died at 3 and he was left an orphan at 11 after his father’s death in 1883. Nevertheless, he completed his high school education, and at 17 embarked alone for America, arriving in Inman in 1889.

In addition to Enns relatives, Cornelius and Elizabeth knew many fellow immigrants. For example, many of the people from their their village in Russia, Gnadenfeld, also immigrated to south central Kansas and created the settlement of Gnadenfeld, Kansas, which today is known as Goessel, about 23 miles from Inman. In its early years, Gnadenfeld operated as a communal village before families moved out to farm larger parcels of land. Peter Shroeder, one of Cornelius’ best friends from Gnadenfeld, Russia, also lived in Goessel.

BIRTH OF INMAN, THE MILL

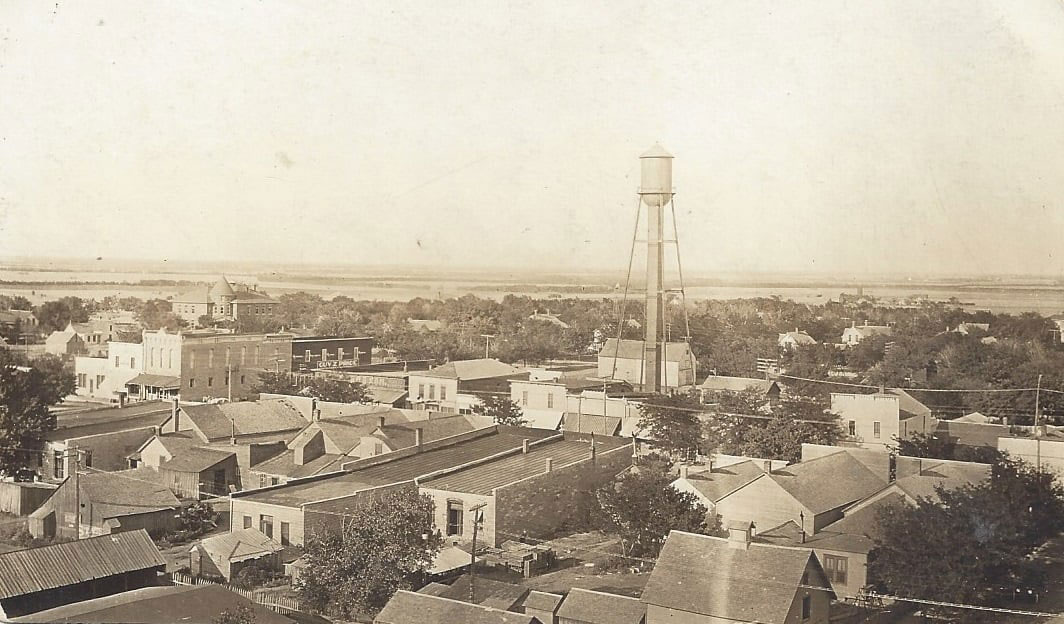

The Enns farm was a mile north of what would become Inman. The settlement was founded as Aiken in 1887, the same year the Chicago, Kansas and Nebraska Railway came through and established a stop.

Aiken, whose name came from a district commissioner, was renamed Inman in 1889 after Kansas settler Henry Inman, an officer in the Civil War and Indian campaigns who later became a newspaper editor and author of frontier stories. Inman is in central Kansas, about 60 miles northwest of Wichita and lies within McPherson County.

With wheat farms surrounding Inman, the need for a flour mill became intertwined with the town’s development. In 1891, the newly launched Inman Independent newspaper began editorializing on the need for a flour mill. In a February 1892 editorial the newspaper said farmers could make more money if they didn’t have to ship to Chicago or other markets. “If we had a mill at home we could get better prices for our wheat as it would be utilized and consumed at home,’’ the editorial said.

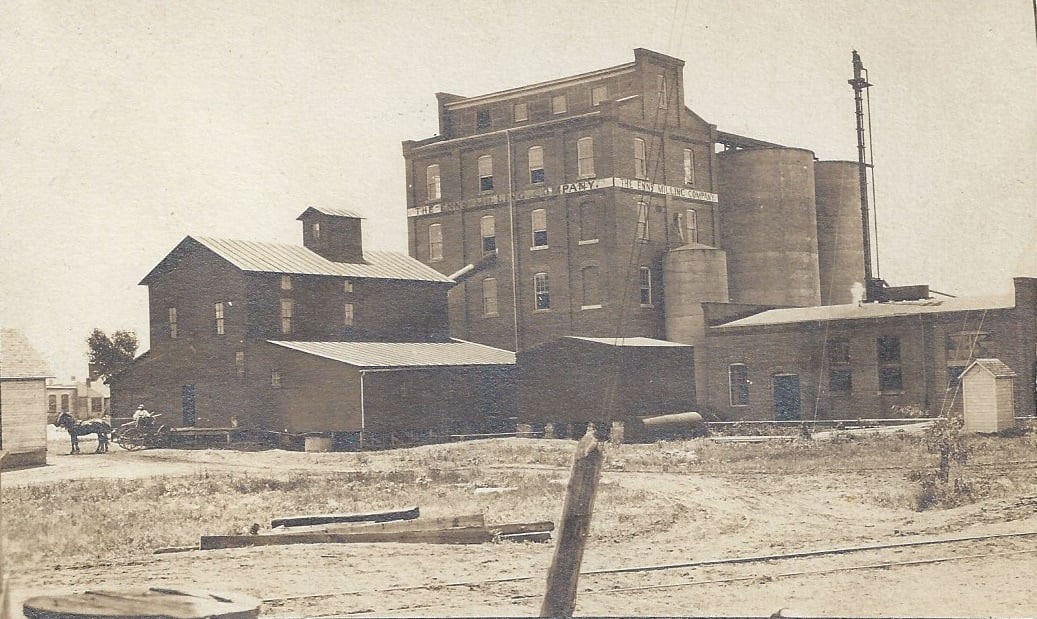

A month later, the newspaper reported that work had begun on a flouring mill. The mill was built by J.H. Stansel and Charles Scott, who soon sold it to John Weisthaner, who called the company Inman Mill and Elevator.

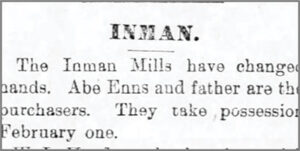

Weisthaner sold the mill to Cornelius Enns and his son, Abraham Cornelius, my great grandfather, in 1894, and the company became known as Inman Mill Co., C. Enns & Son Proprietors. The new owners offered in advertisements in both English and German to chop wheat for just three cents a bushel. Two years later, the price per bushel was advertised at 12 cents.

HARD-WORKING ABE

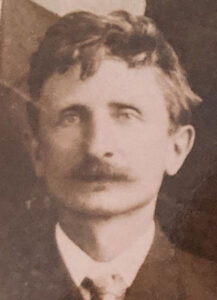

Abraham Cornelius, known as Abe, was the second of Cornelius’ nine sons and a natural to lead the family into its next generation of milling and wheat farming. Cornelius’ namesake and academically gifted oldest son, Cornelius Martens Enns, had decided to go into law instead of farming.

Abe never attended college like many of his other brothers, though he enjoyed an elevated status in Inman’s farming community. He was one of the area’s first farmers to buy a steam thresher, which separated the edible portion of wheat from the straw it was bound to. The device, fueled by straw, was so heavy and clumsy that oxen had to be used to transfer it from place to place because horses were unable to pull it any distance. Later, he purchased two of the earliest coal-burning tractors, farm equipment that proved so unreliable that horses had to be kept nearby in case of breakdowns.

In the community, Abe was secretary of the International Order of Odd Fellows, one of the nation’s most popular fraternal organizations at the time. He was active politically, serving four terms as justice and two terms as Inman’s police judge. He lost the 1900 race for probate judge, despite this endorsement from the McPherson Opinion:

“Mr. Enns is an unusually well-informed citizen, quiet and gentlemanly, and is in every way equipped to make an efficient and popular probate judge. His nomination, which came unsought, is a compliment to the German citizens of our county, and his endorsement in his home and other townships will be most flattering.’’

Besides running a farm and the mill, Abe also ran a meat market with partner Henry Wendt. He was a founder of the Inman Band, playing cornet and tuba, and was a member of the Inman Jockey Club, which held horse races outside of town. Abe was said to have one of the fastest horses.

GETTING MARRIED

Abe married Germany-born Anna Wiegand on Dec. 23, 1889. He was 24 and she was 22. Anna’s mother had died at an early age and Anna grew up with her grandmother. She was unhappy about the arrangement and left Germany for America at the age of 16 to join her aunt and uncle at a farm east of Inman. Unable to speak English on her arrival, Anna had her aunt repeat German words and their English equivalents to her repeatedly and was said to be able to speak English within three weeks, eventually losing much of her German accent.

Anna was Lutheran, and Abe’s marriage to her began a pattern in which most of the Enns brothers would marry non-Mennonite wives.

Abe and Anna had nine children, six of whom survived infancy: Edward, born in 1888; Elizabeth [Sis], born in 1890; Cornelia [Nell], born in 1891; Harry [Snitz], born in 1895; Veola [Lol], born in 1898; and my grandfather, Elmer [Putz], born in 1900.

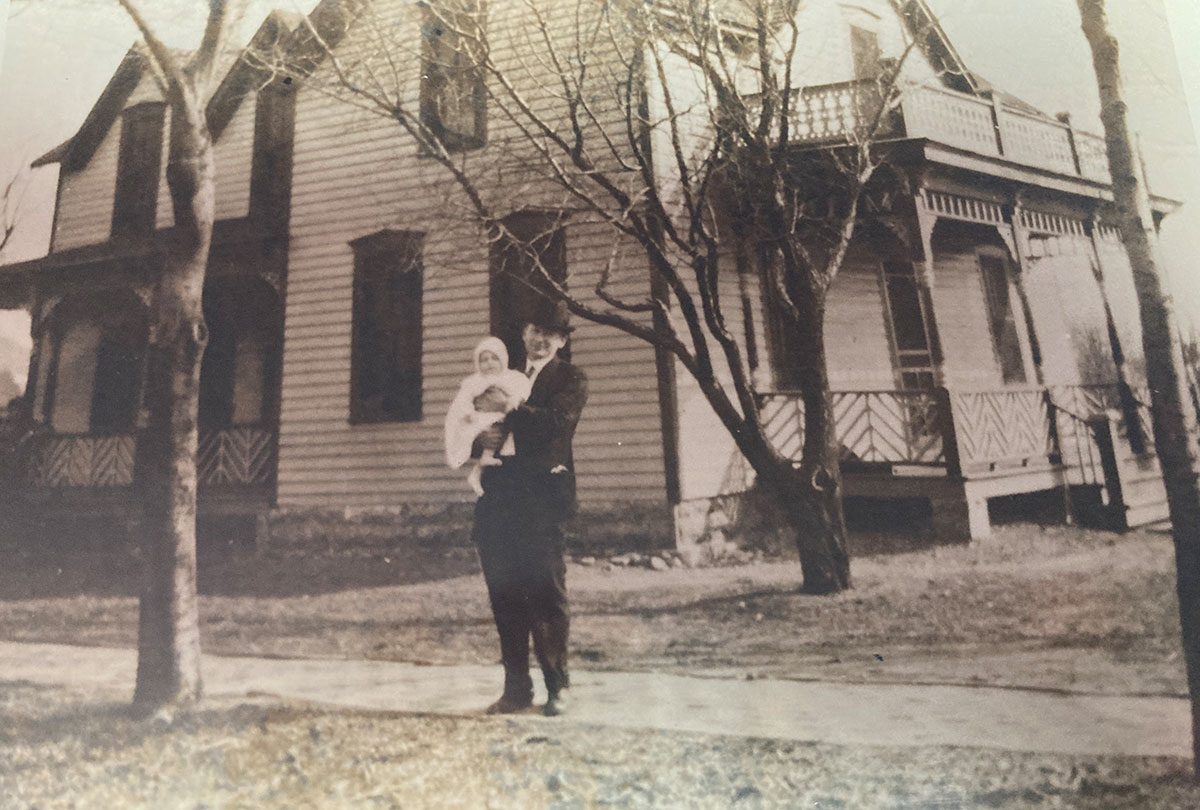

Abe and Anna lived on their farm until 1896, when they moved into Inman. They moved to the Mox Barnow house on Main Street in 1898 before building a house on East Gordon Street and moving into it in 1899. Reported the Inman Review: “His new house is one of the nicest and roomiest houses in the city. Abe never does anything by halves.’’

GROWTH OF THE MILL

After their purchase of the small Inman grist mill in 1894, Abe and his father, Cornelius, built a new mill and in 1896 installed a Corliss engine “that from now on will run day and night in order to supply the demand for their popular brands of flour,’’ the Inman Review reported. The new mill had a capacity of 400 barrels a day and became Inman’s principal industry and largest employer.

By 1897, mill advertisements were promoting three brands of flours, though the mill also ground corn and rye. A new boiler was installed in 1897, a new smokestack in 1899 and a new elevator in 1903. Additional land was purchased around the mill for expansion in 1907.

An 1899 notice in the Inman Review boasted: “Inman has a bank, a flour mill, a creamery, five general merchandise stores, three hardware stores, etc. There’s nothing the matter with Inman. She’s forging to the front.’’

By 1899, the company was being called the Enns milling company by at least one Kansas newspaper, though the mill’s name was not officially changed until 1908, when the company was chartered as Enns Milling Co. with a capital of $60,000, about $2 million in today’s dollars. The family boasted that Enns Milling Co. was the largest independently owned mill west of the Mississippi.

While the mill became Inman’s largest employer, the flour varieties it produced were gaining a regional, if not national, reputation.

FLOUR VARIETIES

In 1895, the mill was producing and selling a label called Russian White Flour. The flour sold for $1, apparently for a large sack. Later the mill would meet all other mill prices and offer their Russian White flour for 75 cents per sack. “Bring your wheat and have it exchanged for flour,’’ the May 17, 1895, Review ad said.

At the turn of the century the mill was also advertising the sale of Snow Flake Flour and, in July 1901, began advertising Enns’ Best, or N’S Best, its premium brand. Said one advertisement: “No matter how expert the cook, first-class bread cannot be made from second-class flour. You must have Enns’ Best. It makes a bigger and better loaf of bread than any other flour.’’

Enns’ Best flour became so popular that a 1910 announcement said one sack of Enns’ Best was being produced every 1-2 minutes of every working day. A 1910 advertisement with this picture boasted, “This mill makes Enns’ Best flour, the best in the world.” Besides Enns’ Best, Snowflake and Russian White, another brand the mill was known to produce was called Sasnak.

TRAGEDY BEFALLS THE FAMILY

The family’s success during the 1890s and early 1900s wasn’t without its tragedies. Herman Enns, the third oldest of the Enns brothers, was committed to a Kansas asylum at the age of 22. Said the April 28, 1892, edition of the Inman Review: “Herman Enns, who is mentally deranged, was taken to McPherson late last week. His condition is a sad one.’’

Herman, who was 11 when the family left Russia, attended school in Inman and became an artist and house painter. “He is kept busy at all times painting signs, residences and businesses, and does good work at reasonable figures,’’ the McPherson Freeman newspaper reported in its June 10, 1887, edition.

At 21, he left for Oregon for a year and returned to Inman. He was baptized in the Hebron Mennonite Church in 1889.

Beginning with his commitment in 1892, he remained at the asylum until his death in 1931 at age 63. His obituary said, “Being of artistic temperament, overstudy made it necessary for him to be committed to an asylum.’’ Overstudy was apparently a reference to what is today known as obsessive compulsive disorder.

When told of Herman’s death, his mother, Elizabeth, was reported to have said, “Now I can die.’’

ANOTHER SETBACK

Another tragedy occurred after the turn of the century when, in late February 1901, Abe Enns was stricken with what some newspaper accounts said was Bright’s Disease, an inflammation and hardening of the kidneys. Despite treatment from two Inman doctors and two additional physicians from McPherson brought in as consults, Abe died at the age of 35 on March 6, 1901.

“He was a progressive and industrious and good citizen and will be missed by the entire community,’’ said the Inman Review, which also noted that all businesses would be closed during his funeral, held at the Inman school house.

With Abe dead and patriarch Cornelius in declining health, running the mill fell to brothers Dick, 23, and John, 21. John, who purchased the family farmstead and paid it off by the age of 19, was considered the financial whiz of the family and became the mill’s president. Dick became the mill’s superintendent, a position he would hold for 54 years.

ANOTHER DEATH

Despite his illness and home confinement, Cornelius remained interested in the mill, with youngest son Nick reading him daily flour receipts in the days before his death in 1905 at the age of 65.

“His spirit of independence made C. Enns a radical in politics,’’ said his obituary, likely written by C.M. Enns, who had become owner and editor of the Inman Review. “Although he never became full master of the English language, being 40 years old when he arrived in America, he soon acquired very accurate information in regard to American affairs and took the best German American newspapers just as in the old country he had been a reader of the Daily St. Petersburg Herald.’’

Years later, William E. Connelly would pay Cornelius a greater tribute in his 1918 A Standard History of Kansas and Kansans.

“To no one class of people does Kansas owe more than to the Mennonites who came out of Southern Russia and applied their experience and methodical industry to the magnificent wheat fields of the Sunflower state. Cornelius Enns was a representative of that class of people.’’

Cornelius’ death occurred at 7:45 a.m. June 1, 1905, the same day his sixth son, John, was scheduled to marry Nuna Cheney, a primary school teacher. Nevertheless, Cornelius’ widow, Elizabeth, insisted that the wedding still take place that day as “the deceased had fully sanctioned the union.’’ The ceremony indeed proceeded, though with only the bridal couple, minister, Nuna’s mother and aunt and uncle the only ones present.

THE MATRIARCH

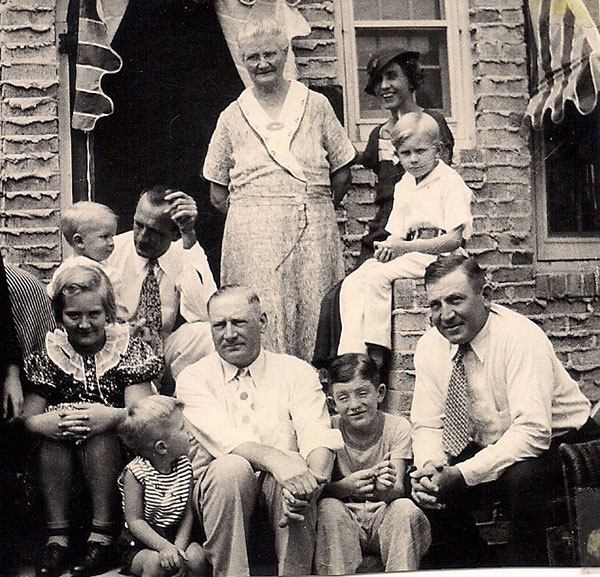

With Cornelius dead, Elizabeth became both titular and de facto head of the Enns family and would remain so until her death at the age of 93 in 1946.

Known as Grossmom, Elizabeth had lived in downtown Inman since 1898, when she and Cornelius moved from the farm, renting it out to Mox Barnow. Her home became the hub for all the clan, with her sons who had left Inman often making a pilgrimage back each Feb. 22 for her birthday.

Though loving, she was also stern, known for wielding a bamboo cane called a rohrstock, which she tapped on the floor insistently to get attention or service, or banged on the stairs to awaken late-sleeping guests.

After Cornelius’ death, son Dick would check in on her daily. Because Grossmom spoke little English, Dick’s wife, Millicent, learned German so she could talk to her.

“She was our queen Elizabeth, in truth,’’ son Henry wrote in his memoir, “and while her scepter was the family rohrstock exacting discipline, her hearty good nature and abundant sense of good humor, plus also her inherent faculty for love and fair play to all, made her the beloved mother she was.’’

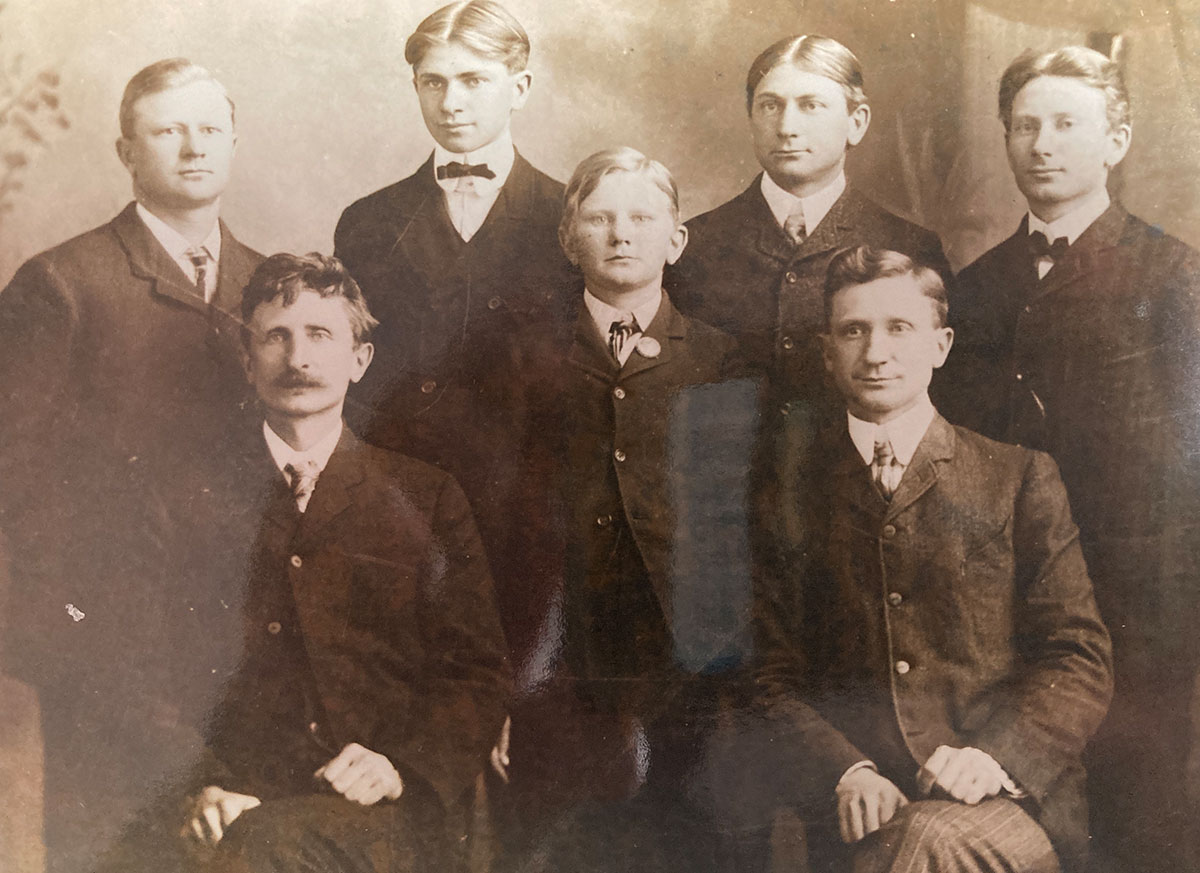

Elizabeth’s sons, the Enns brothers, were a diverse lot and reflected the independence hailed by their father. Whether through education or building up their own enterprises, the Enns brothers were focused on success. Besides Abe and Herman, the other brothers were:

Cornelius Martens (C.M.) Enns, born in Russia in 1862, received his undergraduate degree at Kansas State and his law degree at the University of Kansas. He worked for a loan company in Kansas City before returning to Inman in 1903, purchasing the Inman Review and serving as its editor while also practicing law and serving as Inman city clerk. As a lawyer, he represented many German-speaking farmers whose land titles were being challenged by land speculators. He also helped bring telephone service to Inman, leading the establishment of the Inman Mutual Telephone Co. around 1904. In 1910, he sold the Inman Review to Aaron Dick, who had been at the paper since 1896, and moved with his wife, Ulela Marks, and children, Hilda Marie [Brooks] and Waldo, to California to be closer to her parents. He died in 1940 at age 77.

Henry Enns, born in Russia in 1869, attended Halstead Academy, now Bethel College, after school in Inman. He moved to Little Rock, Arkansas, and worked for the Singer Sewing Machine Co. He met his wife, Florence Gunter, in Little Rock. With Henry still working for Singer, the family moved to Carthage, Missouri, and later Kansas City, Missouri. In 1917, Henry joined Bastian Morley, a manufacturer of boilers and water heaters, and the family, which included sons H.T. [Ted] Jr. and Wilbur and daughter Mildred [Bellows], moved to Evanston, Illinois. He died in 1957 at the age of 87.

Dick Enns, born in Russia in 1876, was 3 when he arrived in America. He attended Superior Grade School near the Enns farm in Inman. He would later marry another student at the school, Millicent R. Luty. Dick finished his education at the German Academy west of Buhler. He was superintendent of Enns Milling Co., a position he held for 54 years. He served on the city baseball team, played tuba in the town band, served on the town board and city board, and was a director of the Farmers State Bank. His outside interests also included harness racing. He and Millicent had three children: Margaret [Klassen], Karl Cornelius, who played quarterback for the Kansas State Aggies in the mid-1920s, and Luty Lee [White]. Dick died at age 73 in 1949.

John F. Enns, born in 1878, was the last child born in Russia and made the trip to America as an infant. He lived in Inman all his life and became president of the Enns Milling Co. after the death of his brother, Abe, and father, Cornelius. Though he had no college education, he was financially astute. He bought the Enns farmstead and paid it off as a teen. He was the longtime president of Farmers State Bank of Inman and was an Inman city councilman and mayor of Inman from 1915 to 1925. He was a financial backer of the family’s foray into Florida, investing in the Maravilla development and a citrus grove in Fort Pierce and the Fort Pierce News-Tribune. John married Nuna Cheney and they had three children: Harlow Cheney, Nuna Lee [Hollow], and Jane [Cables]. John died at age 68 in 1946, the year Enns Milling Co. was sold.

Jacob Harlow Enns, M.D., born in Inman in 1882, was the first of the nine brothers born in the United States. He attended Bethel Academy and in 1907 graduated from Fairmont College. At Fairmont, he was a member of the choir, a solo cornetist and served as president of his graduating class at Fairmont in 1907. He taught math for one year at Bethel College. He graduated from University of Chicago Medical School in 1911 and served internship at St. Margaret's Hospital in Kansas City. He was in general practice in Inman until 1920, when he went to Vienna, Austria, to specialize in eye and ENT medicine. He lived and practiced in Newton, Kansas, from 1922 to his retirement in 1947. He was known to his grandchildren as Grosspapa and his motto was "Keep on Smiling.’’ He married Margaret Klassen, a Mennonite, and they had three children: Eugene Enns, M.D., James H. Enns, M.D., and Anabeth [Youngquist]. Jacob died in 1958 at the age of 76.

Paul Enns, born in Inman in 1885, had bigger dreams than the wheat fields of his native state. After attending Fairmont College, he moved to Kansas City and entered the world of banking. At First National Bank, his co-workers included Harry S Truman and Roy Disney. With younger brother Nick and nephew Putz, Paul moved to Florida in 1923, starting the Maravilla development in Fort Pierce and running and owning the Fort Pierce News-Tribune from 1930 to 1954 and remaining at the paper as general manager until 1962. In Fort Pierce, he married Helen Scott Groh and became the adopted father of her son, Harkless Enns. Paul died in 1981 at the age of 95.

Nick Enns, born in Inman in 1890, was the youngest of the nine Enns brothers. Nick played both baseball and football at Kansas State, where he was known as a “speedy fullback.” In his senior year, he was captain of both teams. He was nearly 25 when he graduated from Kansas State and apparently had spent seven years getting his degree, first at Fairmont College then at Kansas State. After graduation from Kansas State, Nick returned to Inman to work at Enns Milling. The Inman newspaper had followed his college football career with the Aggies closely, and he enjoyed favorite son status when he returned. He married Martha Bartels, a University of Kansas graduate who had grown up in Inman, in 1917, and they had a daughter, Kathryn (Cash). The family moved to Fort Pierce in 1923 as part of the Ennses expansion to the Sunshine State. In Florida, Nick oversaw the creation of the Enns citrus grove, was involved in the Maravilla development and had an ownership interest in the Fort Pierce News-Tribune. Martha died in 1925, and Nick raised Cash as a single father until his marriage to Charlotte Norris in 1934. He died at the age of 59 in 1949.

FRUITS OF FREEDOM

The brothers played a big part in creating what Inman would become in small ways and large.

They helped field the town’s first baseball team, with the 1895 team consisting of Dick Enns at catcher, John Enns at centerfield and Abe Enns at shortstop.

Abe Enns, a cornet and tuba player, helped start the Inman Town Band in the early 1890s and his brothers, Herman and Henry, were in the first band with him.

Until the Enns Milling Co.’s sale in 1946 to Buhler Mill and Elevator, they ran the town’s largest industry for half a century.

Through brother Cornelius, they ran the town’s newspaper and brought the first telephones to Inman.

As the new generation came of age at the turn of the century, the Enns brothers fully embraced their American freedoms.

But they lost something along the way, with many drifting away from the Mennonite religion, whose precepts brought them to America.

Most of them would marry non-Mennonites, and their children would not be raised in the church to which the family belonged for the previous four centuries. They no longer spoke Plautdietsch, the low German dialect developed in Prussia.

They would Anglicize their given names: Henry for Heinrich, Dick for Dietrich, John for Johann, Nick for Nicolai.

They would join college fraternities and fraternal organizations that required the taking of oaths.

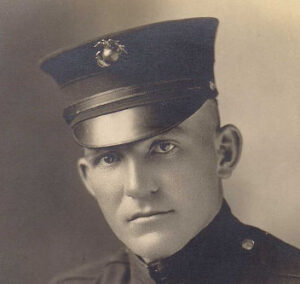

And as the United States entered World War I, counter to the pacifist values that brought them to this country, they would join the military.

The first of their children to do so was Abe’s son, Snitz, who served in the Marines in 1918-1919. My grandfather, Putz, would also serve in the Army weeks before the Armistice was signed before being discharged two months later.

LIFE IN EARLY INMAN

When I was growing up in Fort Pierce, Florida, where Putz had moved from Inman in 1923, I spent a lot of time doing yard work for him. He used German phrases but as far as I know he didn’t speak Plautdietsch.

Among his uncles, Putz spoke mostly about Dick and John, who ran the mill where he worked as a boy. I take it Dick and John were rather stern and exacting. If I did a poor job of raking or sweeping, he’d say he was sure glad I didn’t work for his uncles, Dick or John, at the mill.

Though Putz’s father, Abe, owned the mill with his father, Cornelius, I have no idea what the arrangement was after Abe’s death. When Abe died, the Inman Review reported that he had a $2,000 life insurance policy, worth about $75,000 today. Whatever resources Anna had, they apparently weren’t enough to keep her and her six children going.

According to family interviews conducted by my aunt, Susan Enns Stans, in the 1980s, Anna had to take in boarders to pay the bills and was somewhat dependent on her mother-in-law, Elizabeth, or Grossmom. One of Anna’s boarders was beloved Inman physician J.H. Blake.

As soon as they were old enough, my grandfather and his two older brothers, Ed and Snitz, went to work at the mill.

LOVE OF FOOTBALL

Among all his uncles, my grandfather was closest to his uncle Nick, who was just 10 years older. When Nick returned to Inman after graduating from Kansas State, he served as a volunteer coach for the high school football team, for which Putz played center, “a good passer and a fighter” and his brother, Snitz, played fullback while also serving as team captain.

The team became McPherson County’s undisputed champions. Of Coach Nick Enns, the Inman Review said: “If it had not been for his valuable, free-will coaching, we are sure the team would not have done nearly as well as it did. He was a driver, but the players were all for him.”

When it came to college, Grossmom played an important role in deciding which grandchildren should attend and who should pay for it. Among Anna’s and the late Abe’s children, the green light for college was given to Sis, who attended Bethany College in Lindsborg, Kansas; Nell, who attended Friends University in Wichita; and Lol, who attended Emporia State University. Nell and Lol became teachers while Sis worked for the Internal Revenue Service. The three sisters never married and retired to Colorado Springs, Colorado. On the death of the last sister, Sis, in 1988, they left their estate to their nieces and nephews.

My grandfather’s oldest brother, Edward, worked at Enns Milling and its successor companies from 1908 until his retirement in 1958. He lived in Inman all his life. Like his uncle, John, he also served as mayor of Inman. He also served on the school board and the hospital board and “did “any worthwhile project which would make his town a better place in which to live,’’ his obituary said. He died in 1960 at the age of 71. He and his wife, Merle Hargis, had two daughters, Roberta [Renich] and Suzanne [McEntire].

Edward and Putz’s brother Snitz owned a hardware store in Inman and later worked as a mail carrier. He and his wife, Bernice, had two children, Dr. Mark Enns and Paul Enns. Paul was a pitcher in the New York Yankee farm system in 1946 and 1947 but a shoulder injury dashed his dream of making it to The Show.

My grandfather, Putz, apparently got the nod from Grossmom for college. He followed in the footsteps of his Uncle Nick at Kansas State, pledging Beta Theta Pi, whose chapter Nick founded.

A GOOD RUN

Putz’s college years came after a good run for Enns Milling Co., which had profited handsomely from contracts for flour sold to the U.S. Army and the Allies during World War I, with U.S. wheat crops feeding the troops and civilians overseas.

Poor wheat harvests in 1915 and 1916 had created a shortage of flour, making it impossible for the United States to feed its citizens and the Allies when it entered the war in April 1917. Because the popularity of white bread had also increased demand and driven up prices, advertising campaigns were launched urging U.S. civilians to forgo white bread for soldiers in favor of using other fillers such as cornmeal, potato, rye and others. These substitutes were sometimes called “war bread’’ or victory bread.’’ One pamphlet even stated that these alternative breads are “foods that will win the war.’’

As a sign of its prosperity, Enns Milling barely a year after the war announced that it had built a new grain elevator that could hold 80,000 bushels of wheat.

The success and extra money the mill earned from World War I would undoubtedly lead to brothers Paul and Nick and nephew Putz creating the family’s next chapter, with their move to Florida in 1923.

Gregory Enns is president and owner of Indian River Media Group, publisher of Indian River Magazine. Reach him here.

Gregory Enns is president and owner of Indian River Media Group, publisher of Indian River Magazine. Reach him here.

ENNS OF AN ERA

Read about the Enns family’s migration to Florida in 1923.

Nov. 2024