MISSION ACCOMPLISHED

Retiring IRSC president led college to unprecedented growth, top college status

BY BERNIE WOODALL

It was a hot night in July 1973 as 26-year-old Edwin Massey drove his yellow Volkswagen Beetle along Florida’s State Road 60 on his way to interview for a teaching position at Indian River Community College.

In the passenger seat of the tiny car that had no air-conditioning was his wife, Jo, with their two small daughters in back, tuckered out from a day of battling the way kids in backseats do on long road trips. With only headlights illuminating their way, they drove along the desolate stretch, which locals called Death Road 60.

“You couldn’t tell what was out there,” Massey recounted in his soft Southern drawl during a recent interview. “It was really spooky. We got halfway across 60 and I looked at Jo, and she started crying, and she said, ‘Where are you taking me?’ ”

The family made it to a hotel in Vero Beach, where Jo and the children spent their first full day in Florida playing in the pool while Massey went to Fort Pierce for his interview with administrators, who at that time were led by the school’s second president, Herman Heise.

Massey, who had recently earned a doctorate in zoology with an emphasis in marine biology from the University of Southern Mississippi, was hired as one of three biology teachers. The post paid $13,000, which was way more than he had ever made as a graduate student subsisting on white beans and rice, or before that as a teacher and football coach at his high school alma mater in Laurel, Miss., 90 miles south of Jackson.

The young family moved to Vero Beach by the end of the summer and Massey has remained at the college ever since. Along the way, the Masseys had a third child, and now have six grandchildren.

By 1979, he had moved from the classroom to the first of a series of administrative positions, and in 1988, at 41, he became the college’s third president, beating out experienced community college presidents from Wheeling, W.Va., and Mesa, Ariz.

During his tenure, the institution, formerly known as Indian River Junior College and later Indian River Community College, began awarding four-year bachelor’s degrees and built 71 percent of the nearly 1.6 million square feet of classroom, lab, and operational building space on five campuses in four counties. It also created programs at high schools in all three Treasure Coast counties and Okeechobee County to ensure that students are ready for post-secondary work, whether for an academic degree or a certificate toward a new career.

Massey, 73, retires at the end of August after a 47-year career at Indian River, including 32 years as one of the most successful community college presidents in the country. Last year, IRSC won the vaunted Aspen Prize for excellence among community colleges, signifying it as the best among the 1,100 community colleges in the country.

“If there were a top five community college presidents in the country, I would put him right up there at the top,” said Rebecca Corbin, president and CEO of the National Association for Community College Entrepreneurship. A 2019 book she edited, Community Colleges as Incubators of Innovation, is dedicated in part to Massey and his methods used to prepare IRSC students for an economy that has ever-shifting job demands.

GROWING UP

Massey and a sister were raised by a father who only made it to the eighth grade and a mother who was a registered nurse. His father worked across much of the country on pipelines, a job that kept him away for long stretches when Massey was young. He eventually returned to Laurel, where he started a company that made ornamental iron, opened a floral shop, and was a local elected official for 16 years.

“My father talked with me on several occasions about opportunities missed because he did not have a degree and [told me] that I was going to go to college,” Massey said.

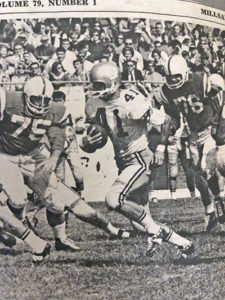

Massey was the kind of kid who was a baseball and football star while also being a bit of a scientist. He was the boy with the chemistry set who also liked to collect bugs. He played halfback on the Laurel High School football team and attended a small liberal arts college in Jackson that was run by Methodists, which would have shocked his grandfather, who was a Baptist minister. He graduated high school at 16 and attended Millsaps College, partly because it would afford him the chance to keep playing sports, graduating at age 20.

Massey won 10 varsity letters at Millsaps, two in track, four in football, and four in baseball, where he started as catcher for four years. He ran the 100-yard dash in 10.2 seconds at the Memphis Relays. He was a halfback on the football team, “5-foot-9, 5-foot-10 and 165 pounds, soaking wet,” Massey said. He wore jersey 41 and caught 39 passes for 429 yards, scoring seven touchdowns, as a senior.

Massey earned a spot in the Millsaps Athletics Hall of Fame for his accomplishments.

He recalled one particular play during a football game at Millsaps.

“I went downfield and the pass was way high,” he said as he demonstrated, reaching as high as he could. “And, you know, that’s the most horrible thing that can happen to a receiver is to get stretched out like that. You are going to get hit right in the ribs or the back. I went up and got the ball, and almost fell down because I was expecting to get hit and nobody hit me. I got my hand down, kept myself up and went about 40 yards for a touchdown.”

FAMILY MAN

Jo Beason and Massey attended the same junior and senior high schools.

“We were at a community dance in Laurel,” Massey recalled. “I looked across the room and saw Jo and asked her to dance, and we’ve been dancing ever since.”

The couple will celebrate their 54th wedding anniversary soon. When they renewed their vows while celebrating their 50th anniversary, they danced to Anne Murray’s Could I Have This Dance, which was featured in the 1980 film, Urban Cowboy.

He had always been a good student, but once he married Jo in his senior year at Millsaps and had their first daughter, Michelle, he took a more determined course.

Massey said that having a wife and a child so young was “probably the best thing that ever happened to me” because “it was time to grow up. It was time to get serious about something and I had something to get serious about. My grades improved. My desire to be more successful improved.”

After graduating from college, Massey taught and coached football for two years at his high school alma mater in Laurel. One day he came home and told Jo he wanted more and that the best path was to go to graduate school, which meant a move to Hattiesburg and the University of Southern Mississippi, where a second child, Kimberly, was born, making it four people living in graduate student housing. A son, Paul, later joined the family while Massey taught biology at IRCC.

At the time, the couple figured that the federal dollars supporting NASA would, after the moon landings, shift to fund ocean research. That would mean a pick of jobs for someone with a doctorate in biology with an emphasis on marine biology, which Massey eventually earned. He says he is still a little surprised that funding for ocean research never really became a federal priority.

So, there were fewer jobs for a marine biologist than the couple had figured. There were some jobs with oil companies and there were some federal positions. But one of them was in the U.S. Virgin Islands, which was a scary place after eight people were killed in a politically motivated shooting in September 1972. And there was a job in New Orleans, which the couple thought would be a great place to have fun but not one to begin a career.

During his time as a graduate student, Massey’s primary mentor and advising faculty member was fond of drinking during school nights. Consequently, that professor would often call on him to teach early morning biology classes for undergrads. It turned out, Massey said, that he liked working with students and that he had a knack for it.

In 1972, Massey left his young family in Hattiesburg to spend a few months of 14-hour days at Duke University’s marine science center on coastal North Carolina. He also was chairman of the Department of Natural Science for the Prentiss Normal and Industrial Institute, one of the first higher education institutions for African-Americans in Mississippi, founded in 1907 and closed in 1989.

GREAT MATCH

Massey said he can clearly remember the first time he walked onto Indian River’s main campus in Fort Pierce.

“It was a really positive feeling. It felt comfortable,” Massey said, looking back to that day nearly 47 years ago. “We talk now how important it is for students to feel comfortable when they get to college.”

In 1978, Massey was named to his first administrative post as the director of public services. Massey said that he did not think he would ever become an administrator. He thought he would teach for a bit and go back to research.

But as he rose through the ranks, he learned he liked the jobs and was good at them.

He became assistant dean of instruction in 1979 and then associate dean of instruction in 1981 and finally dean of instructional services in 1982, essentially the second-most important position for determining the school’s academic heading.

As Massey worked through the ranks at IRCC, demands grew.

“There is no discounting my wife’s role in all of this,” Massey said. “We moved down here and I had to do my job. She never complained and I always had her support. She’s been a major piece of why I was able to do it without feeling guilty about giving up time and so forth. I would work all day and go to community meetings on the road a lot. I can’t recall her ever complaining.”

“You make the time,” he said when asked how he found time to coach youth baseball for about a decade as his son, Paul, grew up in Vero Beach.

Jo Massey also went to work, landing a job at Citrus Bank in Vero Beach, which changed names several times as the banking industry consolidated. After 31 years, she retired as a vice president in charge of several branches when Wachovia was sold to Wells Fargo 11 years ago.

THE PRESIDENCY

When Heise decided in 1988 to retire as IRCC president, having endured a few rocky years that included surviving a Florida Ethics Commission probe, Massey decided to go for the top job.

He said that he and Jo understood at the time that if he tried for the presidency and did not make it, they would likely have to move on to another job, which likely meant leaving the area they’d come to love.

While the IRCC board of trustees voted unanimously to select Massey, some, including the editorial editor of the local newspaper, thought he was tied too closely to the former president. New blood was needed, the editor wrote. But after some time, most on the Treasure Coast, including that editor, warmed to Massey and his way of running the college.

While the last year of Massey’s presidency appears to be sailing along smoothly, his first was tumultuous.

“The day after I got the job, I had to fly to Tallahassee and tell them what I was going to do to improve the college,” Massey said. That was, in part, because a 1986 state audit had identified improprieties with respect to enrollment numbers and grading.

In the first audit of the Massey administration, the state saw IRCC had tightened its procedures. At the time, Massey called the audit “probably the best we’ve had in 10 years.” By the fiscal year ending in mid-1993, IRCC had achieved the first perfect audit in state history, meaning no negative findings, which the college repeated twice more in the decade.

“In the beginning, you had to really be pretty hard-nosed to get the rules, get the regulations, get the infrastructure, to get it back in place and functioning properly,” Massey said.

FRESH OUTLOOK

In the early days of his administration, Massey held staff and faculty meetings in which rank was stripped symbolically and everyone spoke freely. It was like a breath of fresh air for many of them.

“People would say things and then add, ‘Thank you so much for that. I’ve waited 10 years to say that,’ ” Massey said.

By just about any measure, the college has been a rousing success during Massey’s tenure.

It serves more than 30,000 students a year on the Treasure Coast, including part-timers. The full-time equivalent number of students in 2018 was nearly 14,000, up from 5,200 in 1987, the year before Massey took office.

A whopping 96.4 percent of IRSC graduates get jobs or continue their education. The school, at which seven in 10 students also work, has a regular place among the five most affordable U.S. colleges, according to the U.S. Department of Education, and 91 percent of its graduates leave debt-free.

The list goes on and on, just like the long list of awards Massey has won and the national, state and local boards he’s been on and often chaired. For instance, in 2013 the Association of Community College Trustees awarded him the Southern Regional Chief Executive Officer Award and named him National CEO of the Year.

IRSC has provided the Treasure Coast, through its health sciences programs, with many of its radiologists, nurses and medical-laboratory technicians, jobs sure to be in demand as the region’s population grows and its population ages.

The college has a building that looks and acts like a hospital, complete with a bay for ambulances, an emergency room and treatment rooms. And its public safety complex has buildings that are as alike as possible to the jails where future officers will work. And there is a combat village for staging real-life situations that law enforcement officers face.

It is a coincidence that about the same time Massey arrived on campus, the school began precedent-setting national championship runs for the men’s [45 consecutive and counting] and women’s [37 straight and 41 total] swim teams.

The swimming complex, expanded greatly and improved since Massey’s arrival, was near the southern end of the developed portion of Indian River’s main campus in Fort Pierce.

Still in the same spot, the pool complex is now in the heart of campus, widely outflanked to the west by the sprawling Treasure Coast Public Safety Complex where cadets learn the basics of law enforcement and firefighting, where career officers come to update their training, and where accomplished Navy SEALs practice rescue raids. It also houses the area’s most advanced crime lab.

The undeveloped land between the main campus and the public safety complex was purchased at a bargain during the recent recession so IRSC will have enough land for further expansion, Massey said.

SUCCESSFUL LOBBYIST

Even before he became president, Massey was the go-to person when lobbying legislators in Tallahassee for state funds.

He found that he liked the role, and that he also was very good at it. He has been to every legislative session in the state capital since the mid-1980s, meeting with senate presidents and house leaders.

The college’s fund-raising arm, the IRSC Foundation, has seen its assets grow more than 1,700 percent to $116.3 million during his tenure. The foundation offers a cushion that allows Massey’s team to more easily fund programs that prepare students for the ever-changing demands of a shifting workforce.

Asked how a college professor working with petri dishes ended up rising through the ranks of academe with the ability to entice veteran legislators and successful business people to give major funding for IRSC development, Massey said there is no mystery to it. He learned how to work well with people from his mother, who was extraordinary when working with patients and people in general; from his father, who was a longtime politician; and from his grandfather, the Baptist minister.

And out in the community, Massey is an affable evangelist for IRSC. He makes 125 presentations each year in the four-county area.

“He’s an iron man,” said Andrew Treadwell, administrative director of legislative and executive communications for IRSC.

“When I took the job in 1988, I made it one of my priorities to be in the community, to make sure the college is part of the community and vice versa,” Massey said. “It’s amazing how many people don’t really understand a local college and what we actually do and the economic developments we make happen.”

A study of the economic impact of IRSC on the Treasure Coast, conducted in 2012 by the consultant Economic Modeling Specialists Inc., showed that added income due to the college and its former students annually was $1.06 billion, a figure that is surely higher today. The same study showed that for every dollar of state and local tax money invested in IRSC, $2.40 is returned.

As president of IRSC, Massey earns a salary of $375,930. He became eligible for a pension at age 57 under the Florida Retirement System and in 2009, under an arrangement with the IRSC Board of Trustees, he technically retired, enabling him to begin collecting his pension, and then was rehired. His pay is substantially lower than the salaries of presidents within the State University System of Florida.

A 2019 report by WFTS in Tampa Bay revealed that salaries for the five highest-paid presidents in the State University System of Florida ranged from $926,059 for Kent Fuchs at the University of Florida to $505,000 for John Kelly at Florida Atlantic University.

PIVOTAL CULTURE CHANGE

A dozen years into his presidency, Massey had achieved much. The main campus in Fort Pierce and those in Vero Beach, Stuart and Okeechobee were growing, and a new one had been established in the early 1990s at St. Lucie West in Port St. Lucie. By 2000, Indian River was celebrating its 40th anniversary. A new health science center had opened to train health-care professionals. There was a new planetarium. Online classes had begun.

Massey attended a conference where he was impressed by Olaf Isachsen, a Norwegian organizational psychologist. Massey invited him to study the college. He talked to more than 200 employees of all stripes about their working conditions, how this or that program and process was working.

Isachsen gave Massey the results, and they jolted him.

“I could not believe what these people were saying,” he said. “I did not sleep that night.”

Massey was down in the dumps. He wondered whether “we thought we were running something a little better than we were.”

But Isachsen told Massey he should not be hurt, that he had to realize that every one of those more than 200 people loved the college and wanted to help make it better.

So, Massey asked the employees for anonymous replies about the issues that concerned them, even if it may seem trivial such as better air conditioning in bathrooms. Massey hosted nine meetings at various campuses, attended each time by about 100 employees. He told them he was there to listen and respond to the issues they thought important.

It was to be the beginning of a pivotal change, which, Massey said, led to administrators being more proactive than reactive and allowing more people to have a say in how the college is run. Instead of administrators deciding how to design a new classroom building, the task was turned over to faculty members who knew what a classroom needed.

“Yeah, I was a stuffed shirt, at that time,” Massey admitted. “[Isachsen] said, ‘You have to go from formality to informality. Are you showing people that you’re human? You’ve got to be a little vulnerable.’ ”

So started the change in the school’s culture, Massey said. Too many rules and regulations were stifling staff creativity.

“When we freed up people to be creative, innovative, take chances, do things, that’s when we went sky-high on student learning, performance, retention, graduation rate, those kinds of things that allowed us to win the Aspen award,” Massey said.

ASPEN PRIZE

The crowning achievement of Massey’s tenure occurred last year when IRSC won the prestigious Aspen Prize for Community College Excellence, the top honor among the nation’s 1,100 community colleges. IRSC won after being measured on a wide range of attributes of student success, including achievement by low-income students, job placement of graduates, number of graduates and transfers who further their higher education, affordability and more. The Aspen Institute is a nonprofit research institute that tackles a myriad of national and international issues.

“The remarkable thing about Indian River,” said Josh Wyner, Aspen vice president and head of its higher education work, “is that the culture drives toward continuous improvement. I give Dr. Massey and his team … exceptional credit for that.”

INTO THE FUTURE

Massey meets regularly with various work groups and departments across the college, always planning for the future. The president, who shows no signs of slowing down in his last year, says that IRSC will continue to center on what is good for students and what is good for the community and its economy.

Its goals will continue to be flexible enough to adapt to unexpected changes in the area’s needs so local businesses and public and private institutions get employees who will thrive. Focusing on student needs will mean making them comfortable and able to ask for help from IRSC staff. Teachers will also get help to overcome any hurdles to their academic and life successes, be they personal or institutional.

That sounds like a lot. But for IRSC to succeed after Massey is gone, the college needs to do all that. Focus on students. Focus on the needs of the community. Develop principles to thrive by.

As for the future, Massey said he will go into consultancy. He wants to use what he has learned about running a large, highly successful institution that has many of the same needs as a living body, and help others achieve what has been accomplished at Indian River State College. Expect him to do that in his affable, empathetic manner as he helps others help themselves in laying the groundwork for the success of educational institutions and communities for generations to come.

About the Writer

About the Writer

Bernie Woodall is a freelance journalist who began his 41-year reporting career at the IRCC student newspaper and graduated from IRCC with an associate degree in 1977. He later worked for The News-Tribune in Fort Pierce and several other newspapers. He was a reporter for Reuters news agency for 21 years.