Inglorious War

This scene from a James Hutchinson painting on display at Dade Battlefield State Park captures the sacrifice of American soldiers during the Florida War (1835-1842). JAMES F. HUTCHINSON

Soldiers stationed at Fort Pierce fought in unpopular campaign to eradicate Seminoles from ‘worthless’ territory

BY RICK CRARY

Spirits of the old frontier have long since been dispersed in Florida. So, it comes as a great surprise to learn that the Treasure Coast was once a center of conflict in the longest, costliest Indian war in American history. The Florida War stretched from 1835 to 1842.

Later scholars dubbed it the Second Seminole War. The cause was so unpopular that Americans made a hero of the country’s chief opponent: Osceola. Much of the public, including many suffering soldiers, believed Native Americans had always gotten a raw deal. If they wanted waterlogged Florida, why not let them have it, many people conceded.

Maj. Gen. Thomas S. Jesup, the top general in charge of the Florida War, thought American settlers would never be interested in anything below the 28th parallel. On a map today, that would mean all the land south of a line drawn between Melbourne and Tampa. It was nothing but useless swamp, he argued, so let the Seminoles keep it. William Tecumseh Sherman, who would become a famous Union general during the Civil War, thought the entire peninsula was worthless. Sherman served a long tour of duty as a lieutenant in Fort Pierce when he was 21. He wrote in his memoirs that the country should have allotted all of Florida to Native Americans, instead of giving them better lands out West.

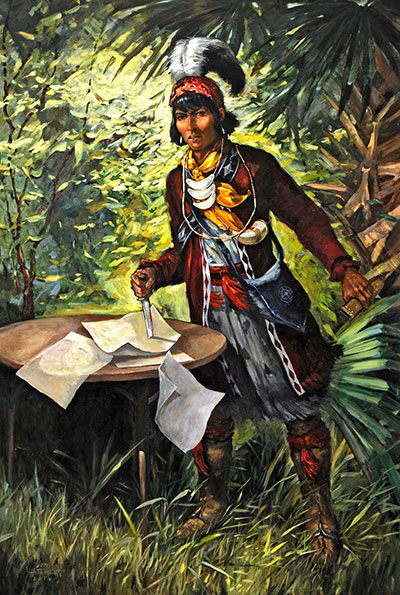

Osceola resisted efforts to remove Seminoles from Florida and earned the American public’s admiration. PAINTING BY JAMES HUTCHINSON USED WITH PERMISSION

PRESIDENTS INSISTED ON MOVE

The administrations of Presidents Andrew Jackson and Martin Van Buren insistently disagreed. The soldiers had to make Florida Indian-free. That’s how Fort Pierce and Fort Jupiter came into being. There were actual frontier forts set up in both locations. And in between was a supply depot on the St. Lucie River, which was too small and temporary to retain an official name.

Among the soldiers who first came to the swampy wilderness of the Treasure Coast was Jacob Rhett Motte, a young Harvard-educated army surgeon. Motte, who exhibited a literary flair, kept a detailed journal of his experiences during the “inglorious war,” as he called it. That’s how we know that on Dec. 31, 1837, at 4 p.m., a regiment led by Lt. Col. Benjamin K. Pierce — brother of a future president — first arrived on steamboats. It disembarked near a narrow inlet, that was situated a mile or so north of where Fort Pierce Inlet is today. Soldiers pitched their tents on the beach and the next morning they celebrated New Year’s Day like tourists, taking a refreshing swim in the ocean. Motte was amazed to discover the air temperature was 80 degrees.

NEW FORT NAMED

On Jan. 2, 1838, the regiment took barges 4 miles south to the highest bluff on the west side of the Indian River. Curiously, Motte observed what he believed were man-made formations around the bluff. He said the way the ground had been worked gave strong indications that the place had been used for fortifications in ancient times. Perhaps by pirates, he surmised. (But might it have been the site of the Spaniard’s ill-fated Santa Lucia?) At any rate, the soldiers spent the day constructing a blockhouse on the bluff. It was much like any other frontier military blockhouse of the era, Motte said, except that it was made with palmetto logs.

“We deemed it worthy of the title of fort,” Motte wrote in his journal, “it was therefore dubbed Fort Pierce, after our worthy commander.”

Less than two weeks later, Jesup arrived with a thousand more men. He was assembling his troops for one of the biggest campaigns of the war, he created an intricate network of forts and depots across the state. With troops crisscrossing back and forth, his plan was to force the Seminoles southward and away from settlements in northern Florida. He wanted his enemy to concentrate its forces for battle, instead of peppering troops and settlers with hit-and-run guerilla tactics.

His strategy seemed to be working. Just three weeks before, on Christmas Day, Col. Zachary Taylor ran into a large force of Seminoles congregating near the north side of the big lake. The Battle of Lake Okeechobee, which became the largest battle of the war, was fought to something of a standstill, with the Indians moving further south, as Taylor took his dead and wounded north. While searching for the Seminoles, a large scouting party from Fort Pierce suffered heavy casualties in a skirmish. Survivors brought back news that the enemy was amassing in large numbers 30 miles south of the new fort. Jesup would go after them right away, via the vast Al-pa-ti-o-kee Swamp.

RELUCTANT LEADER

But the general was leading a war he never wanted to fight. When he first took over the job, he had tried so hard to make it end without more bloodshed. So, how did it all come about?

For more than a century before Florida became a U.S. territory, Native Americans from the Creek Confederacy and other tribes fled to Florida in an effort to retain their way of life. They were joined by runaway slaves. Together they banded in a loose association that became known as the Seminole Nation. While Florida changed hands back and forth between Spain and England, the Seminoles were allowed great freedom. But a few years after America wrested Florida from Spain, President Jackson, a notorious Indian fighter, signed the Indian Removal Act of 1830. That law decreed that the Seminoles were no longer welcome east of the Mississippi.

When they were told to move out West, most Seminoles pretended relocation would be OK. But under Osceola’s guidance, they began storing up gunpowder and other supplies. Gen. Wiley Thompson, the federal agent in charge of Indian removal, made note of the hoarding, which he thought looked suspicious. It wasn’t long before Thompson was dead and minus a scalp. Some pioneers also got scalped. Suddenly, no cabin in the wilderness was safe; and every big coastal plantation south of St. Augustine was attacked and destroyed.

When federal reinforcements under Maj. Francis Dade were massacred out in the middle of nowhere, the war began in earnest. Settlers were murdered in gruesome ways that evoked tremendous panic. For safety, all the pioneers had to hole up in crummy, makeshift stockades scattered around the upper half of Florida.

JACKSON INSULTS MILITIAS

President Jackson lost patience with the men of Florida for not putting down the uprising with their militias. He invited them to go get shot by the Indians so their wives could remarry better husbands. As an added insult, the president boasted that, old and crippled as he was, he could take an army of 50 women down to Florida and whip every Seminole in three weeks. Instead, Jackson gave Jesup the onerous task.

“This is a service which no man would seek with any other view than the mere performance of his duty,” Jesup said prophetically, as quoted in the Niles Weekly Register of March 11, 1837. “Distinction, or increase of reputation is out of the question; and the difficulties are such, that the best concerted plans may result in absolute failure, and the best established reputation be lost without a fault.”

By the time the main action reached the Treasure Coast, Seminole leaders had pretended to give up several times. Surrendering always helped them get more supplies from the government, including the gunpowder they needed for hunting deer and other game. Jesup got fooled the worst.

During his first months in command, Seminole leaders agreed to attend a peace conference. By the end of the talks, they had Jesup so convinced that their people would exit Florida, he publicly announced the war was won. Most of his troops were allowed to go home to their respective states. Settlers joyously left the stockades and returned to their isolated cabins.

As promised, much of the Seminole Nation arrived at a growing encampment near a makeshift harbor in Tampa Bay, but the Indians kept delaying their departure. They all needed to go out West together, they explained. It would take a while to gather all their people. They couldn’t leave stragglers, like Osceola, behind.

FOOLED BY OSCEOLA

Osceola was the fiercest, most determined — and reputedly, the most handsome — opponent of removal. The war wouldn’t be won, if Osceola stayed behind with a band of followers. So, Jesup patiently bided his time. Finally, one night Osceola showed up at the encampment, but in the morning everybody was gone. Vanished. The whole Seminole Nation — men, women, and children — melted back into the wilderness. Worst of all, enough supplies were hauled away to keep the war going strong.

Well, you can imagine how badly Jesup must have felt when he saw all the empty chickees. Worse still, he had to endure some really bad press. Settlers weren’t happy about having to scramble back to those miserable stockades. The army had to be reassembled posthaste. And back home in Kentucky, Jesup’s wife, Ann, got sick of reading all the political commentary about her husband being an idiot. Jesup tried to resign, but newly elected President Van Buren wouldn’t let him quit.

That’s when the general decided the only way to win quickly, as the War Department and angry newspaper editors demanded, was to fight ugly. The next time Seminole chiefs and warriors came in under a white flag to barter for more supplies, he would snooker them. Sure, a white flag means truce sometimes, but it also means surrender. Right? The chiefs who stiffed him had surrendered already, fair and square. So they were like escaped prisoners now. Why couldn’t he just arrest them? That’s how Jesup saw it.

Soon, Jesup nabbed every chief and warrior he could get his hands on, including the public’s darling: Osceola. But the national press cried foul. So did some members of Congress, plus most historians ever afterward. Nevermind that he was trying to end the war without anymore soldiers — or Indians — getting killed. He cheated, his detractors decried. It didn’t help when Osceola suddenly died in captivity of a serious case of tonsilitis a few months afterward. The public was rightfully enthralled to learn the valiant Seminole leader chose to meet death with his war paint on. His portrait became a hot commodity. But poor Jesup’s treachery made him a national villain.

Capturing the Seminoles’ biggest chiefs should have ended the war, but it slugged on for four more years. Wildcat (also known as Coacoochee) was as bold and dangerous as Osceola, but never quite as famous. After Wildcat was tricked into giving up, he made an incredible escape from a dungeon in St. Augustine. He and a bunch of his warriors slipped through a tiny air hole in Fort Marion (aka Castillo de San Marcos) and made a long drop down into a moat. With Wildcat on the loose, the Seminole Nation had another inspiring leader to keep them going.

After Osceola’s death, it was said that Wildcat became the leading war-spirit of the Seminoles. PAINTING BY JAMES HUTCHINSON USED WITH PERMISSION

SERVED COUNTRY UNSELFISHLY

Jesup may have looked like a double-crosser to most folks back home, but he really was the epitome of the self-sacrificing soldier. He carried out orders at great personal cost and pressed onward with his thankless task. On horseback and on foot, he followed the tracks of scattering Seminoles into South Florida’s uncharted swamps — with all the world against him. Even the hot, muggy climate and tangled terrain were fighting on the Seminoles’ side.

Jesup’s strategy brought him to Fort Pierce, from where he led his army westward through forbidding marshland to make a juncture with yet more troops. And then they headed southward, looking for one big battle. As they marched through the region there was something aesthetically arresting about the primeval wetlands. Motte, the surgeon, reveled in the exotic scenery. He painted the setting with words, describing it as a region where “a landscape painter would delight to dwell.”

“The whole country, since leaving Fort Pierce,” Motte wrote, “had been one unbroken extent of water and morass… Nothing can be imagined more lovely and picturesque than the thousand little isolated spots, scattered in all directions over the surface of this immense sheet of water, which seemed like a placid inland sea shining under a bright sun. Every possible variety of shape, color, contour, and size were exhibited in the arrangement of the trees and moss upon these islets, which, reflected from the limpid and sunny depths of the transparent water overshadowed by them, brought home to the imagination all the enchanting visions of Oriental description.”

It took days of sloshing through transparent water to reach the high-and-dry hammocks near the Loxahatchee River west of Jupiter Bay, where Seminole warriors were lying in wait. Half of the soldiers had lost their shoes in the muck. Sharp-toothed edges of saw palmetto stalks tore holes in their pants and chewed painful scrapes into their skin. The men drank swamp water and many were ill. (More died from disease than fell to the enemy.) Hot sun and a million bugs relentlessly triggered discomfort. Sleeping on the spongy ground brought little relief in their soggy, foul-smelling attire. And at the end of suffering days and nights came a deadly battle.

SOUNDS OF WAR WHOOPS AND CANNON

On Jan. 24, 1838, the advance guard was fired upon. As soon as Jesup heard the news, he gave orders to attack. The quiet of midday gave way to a tremendous cracking sound of men rushing forward through a sea of palmettos. The pace of their charge was suddenly slowed by a half-mile wide slough full of cypress knees. Hidden in the thick jungle looming on the horizon, they knew their enemy must be lying in wait with loaded rifles.

As the first line of soldiers made their approach toward the dense foliage, a terrifying war whoop from hundreds of warriors suddenly filled the air to the accompaniment of clattering rifle fire. Some men fell, and the battle was on. Artillerists quickly set up field guns, and then grape shot blasted toward the smoke of the Seminoles’ muskets. For added effect, the army launched crude Congreve rockets, which made plenty of terrifying noises, but rarely hit on target. Following the deafening bombardment, the soldiers charged.

Reenactors cover their ears while firing a cannon during the February reenactment of the Battle of the Loxahatchee. RICK CRARY

As commander of the entire war effort, Jesup should have remained outside the range of the Seminoles’ rifles. But on one side of the field of battle, he saw hundreds of militiamen holding back from entering the woods and confronting the Indians head-on. Impulsively, Jesup jumped off his horse, took out his pistol and led them in a charge. Forward he ran ahead of them all, splashing through the swamp and into the forested higher ground of his enemy.

Was Jesup recalling days of his greatest triumph? At age 25, he became a hero at the Battle of Lundy’s Lane, which took place within the roar of Niagara Falls. In one of the bloodiest battles of the War of 1812, he was struck by bullets and shrapnel: in the shoulder, in the neck, in the chest and in his right hand — which was lastingly disfigured. Knocked down by the blast to his chest, he stood back up and rallied his men to fend off a relentless British onslaught. Jesup’s gallantry that day resulted in a glory that included a series of rapid promotions, which made him a general by the age of 29.

HE CHARGED ALONE

Now the 49-year-old scorned commander was running, running — charging once again — in reckless disregard of his life, into the thickness of the hammock where he could barely see a few feet ahead. He pressed forward to the edge of a beautiful, rapidly moving river he had never seen before. That’s when he looked over his shoulder and found he was alone, his orders disobeyed. My God! No one had followed. He made the charge alone. Jesup looked back across the river to danger.

That’s when a Seminole’s bullet found him. It came from the other side of the Loxahatchee and struck him squarely in the face. Ricocheting off his spectacles, it gashed his left cheek, just below the eye. But the bullet didn’t penetrate the bone. In the heat of battle, the Indian who shot him may not have packed his rifle with enough gunpowder to make the little, ball-shaped missile penetrate the skull. Jesup dropped to the gnarly, humus-covered ground and felt around for his glasses. He collected the pieces and retired to the care of his surgeon.

Although the general’s one-man charge may have become a source of levity in camp, he and his hardest-fighting troops won the Battle of Loxahatchee that day. Afterward, hundreds of famished, destitute Seminoles surrendered and begged for corn. In spite of the battle and the awful ache from his wound, Jesup took pity on his enemies and sent another letter to Washington attempting to persuade the government to let them keep South Florida.

It sounds bizarre, but while the combatants were awaiting the government’s slow response via the mail, they threw a big party together. Officers brought the booze and Seminoles taught the soldiers how to dance around a bonfire. Motte especially enjoyed watching pretty Seminole women dancing with rattles made from little turtle shells tied around their bare legs. In the end, the decision from Van Buren remained the same. The Seminoles must go.

LAST HURRAH

Loxahatchee was to be Jesup’s final hurrah in Florida. On April 10, 1838, he was ordered to turn over command to Col. Taylor, who would later become the nation’s 12th president. Afterward, Jesup asked the Treasury Department to replace two horses he lost during his service, but reimbursement

was denied.

After Jesup left, the Florida War devolved into little more than an endless Indian roundup. Soldiers tried to chase down little bands of guerilla fighters here and there, including Wildcat and his gang. By 1842, the government finally gave up and let the last 300 or so Seminoles remain at large. Happily, eradication of their culture was never completed. But Wildcat did move West. Before he left, he said his dead twin sister brought him a vision of a more perfect world, where one day he would meet the Great Spirit.

“Game is abundant there,” Wildcat said, “and there the white man is never seen.”

Jesup went on to serve as quartermaster general until his death in 1860 at the age of 72. From his administrative offices in Washington, Jesup’s efficient paperwork kept the nation’s military supplied as America expanded its reach across the vast continent. In total, he served his country for 52 years with quiet fortitude and unheralded distinction.

As for his overlooked mark on the Treasure Coast, Jesup was the commander who ordered the establishment of Fort Pierce. Young Lt. Sherman was stationed there in 1841 when Wildcat surrendered to him. By then, the fort had been expanded to include additional palm-thatched buildings and a typical stockade wall. Although the actual fort burned down Dec. 12, 1843, the name has always remained as a clue that big things happened there long ago. Forgotten heroism, for instance — and a powerful clash of cultures that made our world what it is today.

Someday, we might take pause to favorably recall those thousands of soldiers who thanklessly tramped through Treasure Coast swamps, as Motte wrote of his fellow patriots, “…enduring with patient long suffering the toils and discomforts of an inglorious war…with no prospect for gathering laurels; but all endured from a high and unselfish esprit de corps, and a cherished enthusiasm in the service of their country.”