Growing pains

SPILLMAN COLLECTION, ARCHIVE CENTER, IRC MAIN LIBRARY

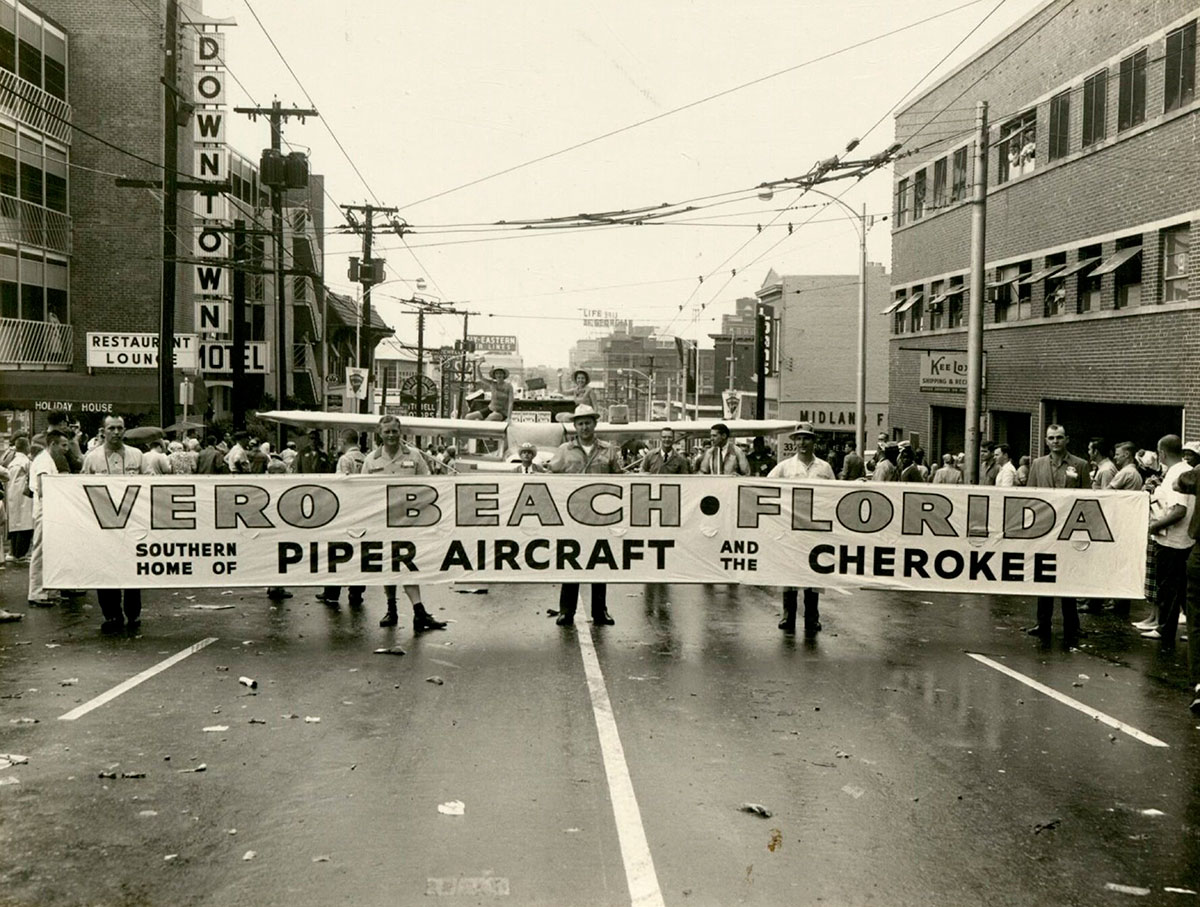

By the 1960s, Vero Beach exported the message of its success, including its boast as the home of Piper Aircraft, to places such as a parade in Atlanta.

Transportation, technology advances spur population surge after the war

BY JANIE GOULD

Better bridges and roads, mosquito control and eventually, the widespread use of air-conditioning, even in public schools, made Vero Beach attractive to new residents during the postwar Baby Boom.

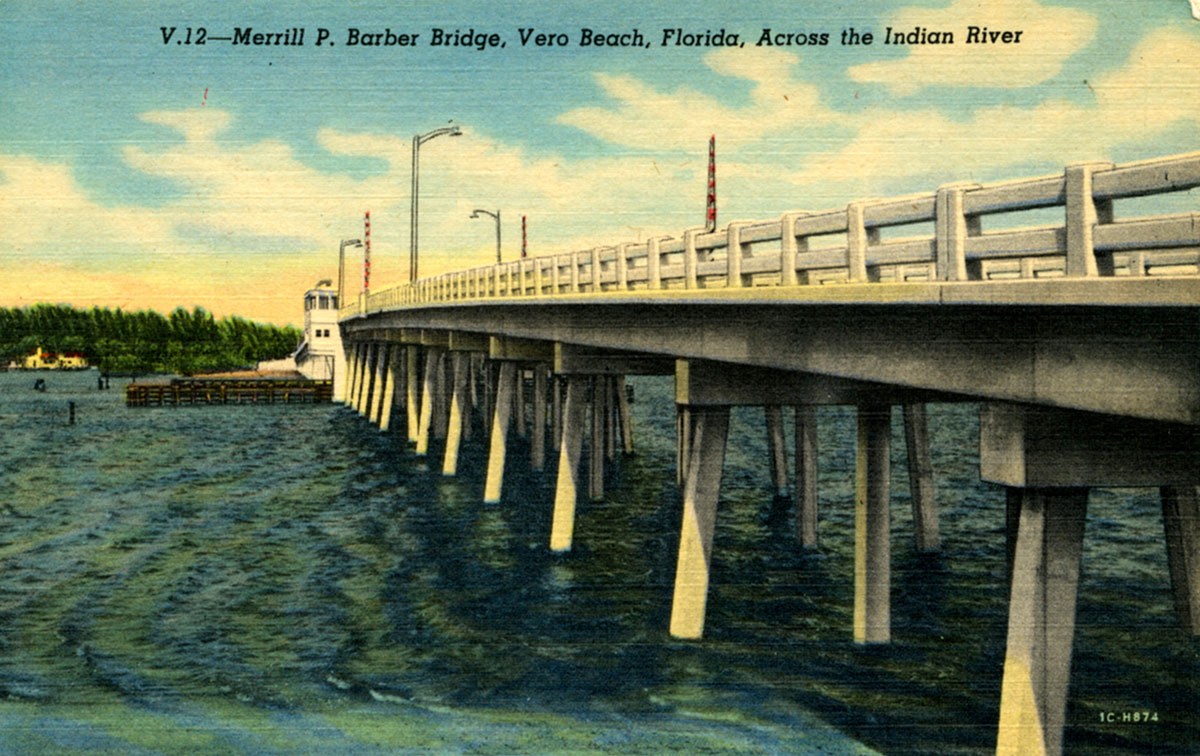

Vero Beach’s only bridge across the Indian River lagoon was a narrow, hand-cranked structure built in 1920. Local banker Merrill P. Barber was serving on the State Road Board and in the state Senate in 1949 when he helped secure funding for a new bridge.

Barber’s daughter, Helen Stabile, remembers what it was like to cross the old wooden bridge in her parents’ car.

“It went clickety-clackety, clickety-clackety all the way over,” she said in a 2006 interview for the WQCS radio oral history project.

“People were always fishing on it. It was probably one of the few bridges in the world that had a curve in it. The drawbridge part of it was literally cranked by one hand. It would swing outward, not go up.”

The bridge tender, Ben Wood, and his family lived in a house on the bridge.

While the newer bridge, a concrete structure with an electric draw span, was being built, Barber took a keen interest in its progress, said his younger daughter, Merrill Dick.

“Every night after dinner Daddy and I would take a walk,” she said. “Usually I was barefoot and by the end of the night I would have bloody toes from stubbing them. We would walk from our house on Royal Palm Place to the construction site, and Daddy would be so interested in everything that transpired that day and the challenges the men were having. Even after it was completed, there would be times when he would want to walk to the bridge and talk to the bridge tender.”

SMITH COLLECTION, ARCHIVE CENTER, IRC MAIN LIBRARY

The original Merrill P. Barber Bridge, which opened in 1951, provided easy access between the mainland and the barrier islands in postwar Vero Beach.

PARK AND BRIDGE DEDICATED

Stabile, who was in college, and Dick, who was 5 or 6, remember the bridge dedication in 1950 as “quite an event.” It took place the same day that the nearby MacWilliam Park was dedicated in honor of mayor and legislator Alex MacWilliam, who was in the hospital, the sisters said.

The 1951 bridge eventually became inadequate for the growing community. The draw span seemed to be raised more often than not, causing regular traffic tie-ups. In 1995, the new fixed-span bridge was built and again named for Barber, who died in 1985.

“I remember dad saying it was becoming a very dangerous situation,” Stabile said. “The beach had built up so much and he was worried about people trying to get to the hospital. He was anxious to see it replaced. I don’t think when he passed away he had any idea it would remain the Barber Bridge.”

The Intracoastal Waterway was also improved during the postwar era, thanks to an incident in Vero Beach involving President Harry Truman.

STUCK IN THE MUD

Truman was en route to Key West in 1950 when his yacht ran aground near Vero Beach, said William Crawford, author of the book Florida’s Big Dig: The Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway.

Even though Congress had decided in 1945 to widen and deepen the waterway, most members opposed using federal funds for that purpose, Crawford said in a radio interview. Truman felt the same way until he was inconvenienced in Vero. A yacht carrying the former assistant secretary of the Navy was also cruising south.

“According to the mayor of Vero Beach, Alex MacWilliam, both yachts were grounded in the Vero Beach area,” Crawford said. “As a result, Congress got into action and in 1950 passed the necessary funding to increase the depth.”

By 1960, the channel had been dredged to a depth of 12 feet south to Fort Pierce, Crawford said, and he thinks that wouldn’t have happened if Truman’s yacht hadn’t run aground.

“There probably wouldn’t have been any funding, because there was a big fight at that time,” he said. “It’s a fight that goes all the way back to the founding of the nation, when people in Congress felt that the inland waterways were local and state problems, not federal problems.”

TURNPIKE A GODSEND

Land transportation also became better in the late 1950s with the opening of the first leg of Florida’s Turnpike, then known as the Sunshine State Parkway. The 107-mile stretch from Miami to Fort Pierce reduced the time it took to drive from Vero to Miami from roughly four hours to two. Billboards advertised that motorists could avoid “100 stoplights” by taking the turnpike rather than U.S. 1.

Vero Beach retiree Victor Dacy was a University of Florida freshman from Miami in 1947 when he first made the 365-mile trip from his home to Gainesville.

“It took us a day and a half to get there,” he said in a radio interview. “U.S. 1 was two lanes. We had to go through every little town on the east coast of Florida: Fort Lauderdale, West Palm, Stuart. I can remember going along the Indian River in the fall. The sulphur smell was predominant.”

Dacy was out of college when the turnpike opened in 1957, and his work in the citrus industry required him to drive all over the state.

“The turnpike was really a godsend, because you could go 50 miles an hour or so,” he said. “It made life a lot easier.”

MOSQUITO WARS

Modern measures to fight mosquitoes began in Vero Beach during the closing months of World War II. The Navy, which operated a naval air station at the city airport, announced plans to use DDT against the insects in the air and on the ground. The base newspaper, The Buccaneer, reported the news on April 19, 1945, with a headline, “Vero Mosquitoes Under Attack.” The story shared front-page space with a photo of a flag at half-staff in honor of President Franklin Roosevelt, who had died a week earlier.

The Navy did aerial spraying of DDT on 40 square miles of salt marsh around Vero, and painted a mixture of the pesticide and diesel oil on window screens in barracks, the dispensary, mess hall and other buildings at the air station. Sacks of sawdust saturated with DDT were dropped into pools of stagnant water where mosquitoes were likely to breed.

The Buccaneer reported DDT was working well, but told readers not to become complacent.

“It’s a safe guess to say that we’ll still be cursing the bites this summer,” the newspaper said. “DDT is here as a control, not an eradicator.”

DDT became available for civilian use after the war. When John Beidler of Vero Beach became director of the Indian River Mosquito Control District in 1955, there was no shortage of the noxious little pests. Mosquitoes were often so thick that 50 to 100 of them would land on a human tester in a minute or less, he said in a radio interview.

“When I first came, they were using some mist blowers or dusting machines,” he said. “They were quite cumbersome, so we began using what are called thermal fog machines. The insecticide was dissolved in diesel oil and heated up to 1,000 degrees. Then you would spray it into the air as a vapor, which made a huge cloud of fog. If you had the right insecticide it would kill some mosquitoes, and also, unfortunately, attract children.”

SPRAYING WAS DANGEROUS

Jerry Doutrich, living in Vero’s Beattyville neighborhood at the time, remembers running into the fog.

“When we would hear the truck, we would stop playing hide-and-seek or whatever we were doing and hold our breath while running or riding bikes behind the truck,” he said. “I can feel and taste the droplets as if it were today.”

Beidler said most towns in Florida used fog machines at the time.

“Any time we saw a lot of kids running in and out, we made an announcement that if we saw that sort of thing going on we weren’t going to fog that area because we thought it was dangerous, not because of the DDT or the BHC or whatever it was, but because of traffic. Cars zipped in and out of that fog and we were just scared to death that some kid was going to get run over.”

Beidler said there were no traffic injuries, and some residents complained that the trucks were driving too fast.

“The fastest we ever went was 5 miles per hour, which was a big problem because you couldn’t get anywhere. In four hours, you’d go 20 miles and 20 miles of streets is not much.”

The assault on mosquitoes helped open Vero Beach to summer tourism and outdoor attractions. The Vero Drive-In was launched in 1950 to offer inexpensive entertainment to families with young children. Admission was 44 cents for adults and free for children, said Jack Chesnutt, manager until the drive-in closed in 1980. Hot dogs and drinks were 15 cents each.

“We did have lots of mosquitoes,” Chesnutt recalled in a radio interview. “I got DDT spray from Mosquito Control. We had 55-gallon drums on the back of a truck and it went through the exhausts. We sprayed for mosquitoes and it really made a difference.”

The federal government banned the use of DDT in 1972 after Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring showed the pesticide posed a danger to birds and other wildlife.

SHOPPING IN COMFORT

Air conditioning also improved life in Florida, but it didn’t become widespread until the 1970s. Historian Gary R. Mormino says in his book, Land of Sunshine, State of Dreams: A Social History of Modern Florida, the cooling technology was available 20 years before the average resident could afford it. Richards Department Store in Miami started advertising window units in 1945, he said, but less than 20 percent of all homes in the state were air-conditioned in 1960.

Wodtke’s Department Store on 14th Avenue was one of the first stores in Vero Beach to have air conditioning, co-owner Kay Wodtke Trent said in a radio interview. Her father, Bill Wodtke Sr., opened the store in 1942 and by the early 1950s had installed air conditioning.

The store had a sign in the front window that told sweltering passers-by about its comfortable interior.

“You had to put that in your advertising,” Trent said. “It was a drawing card to get people to come in.”

HOT DEBATE OVER COOLING

Air conditioning was important not just because of the comfort factor but also because of the dictates of fashion, even in small-town Florida.

“At that time, women weren’t completely dressed up if they didn’t have hats and gloves,” Trent said. “You always had a girdle and stockings on. It didn’t matter how hot it was. That was the thing to do and we all did it.”

The schools in Vero Beach, jam-packed with baby boomers in the 1950s, had strictly enforced dress codes — no shorts or T-shirts allowed, of course — and no air conditioning until the mid-’60s or later. Teachers often had small electric fans on their desks that allowed stifling air to circulate a little bit.

An Indian River County bond issue to finance the construction of new schools in the 1950s failed at least in part because of concerns from some voters that air conditioning would be a frill.

Mormino said that thinking wasn’t unusual at the time.

“Cooling Florida’s schools ignited a hot debate,” he wrote. “Many old-time residents and transplanted seniors argued that sweating (along with shivering and walking long distances) bred character, and besides, taxpayers could not afford the luxury.”

GROWTH TAXED SCHOOLS

When Ouida and Jack Wyatt moved to Vero Beach from Tennessee to teach in 1956, there was one public elementary school in the city, along with Vero Beach Junior-Senior High School.

“My husband’s first job was teaching physical education at the elementary school,” Wyatt said. “He taught two classes at a time and the classes averaged over 40 children, so he had around 80 students each 30 minutes of the day, except for one 30 minute period he had off. The schools were unbelievably overcrowded. I believe there were about 1,000 children in the first six grades.”

In the 1950s, many girls wore crinolines under their skirts, which made the school hallways even more crowded when students were changing classes. Ouida Wyatt taught physical education at the time.

“Out in the locker room it was so crowded with all those crinolines, because the girls had to wear uniforms for physical education, that I put I bolts in the ceiling and ran wires and took clothespins to hang the crinolines up over our heads, so I would have enough room to see what was going on the locker room,” she said. “You had seventh-graders through 12th-graders in the locker room all the time. You could just barely squeeze around in there.

“It was a sight in the hall when you had all those crinoline skirts and girls holding them as they walked down the hall,” she said. “It was crowded. It was unbelievable. At one time, it was so crowded that if you had study hall and the weather was good, you just went out and sat on the ground outside.

“People were moving in to Vero like crazy,” she said. “Every year they had to search for teachers. Vero Beach was a wonderful town. It was not like small towns in Kentucky and Tennessee, where if your grandfather wasn’t born there you were an outsider. A lot of the stores in Vero gave teachers 10 percent discounts. Ten percent off shows you how badly they wanted teachers and wanted to keep them.”

In the late 1950s, voters finally approved a bond issue that financed the construction of three new elementary schools in Vero Beach — Rosewood, Beachland and Osceola — and, in 1964, a more modern high school. The high school was air-conditioned, but it took another decade before cooling came to all of the county’s public schools.