Century of progress

SMITH COLLECTION, ARCHIVE CENTER, IRC MAIN LIBRARY

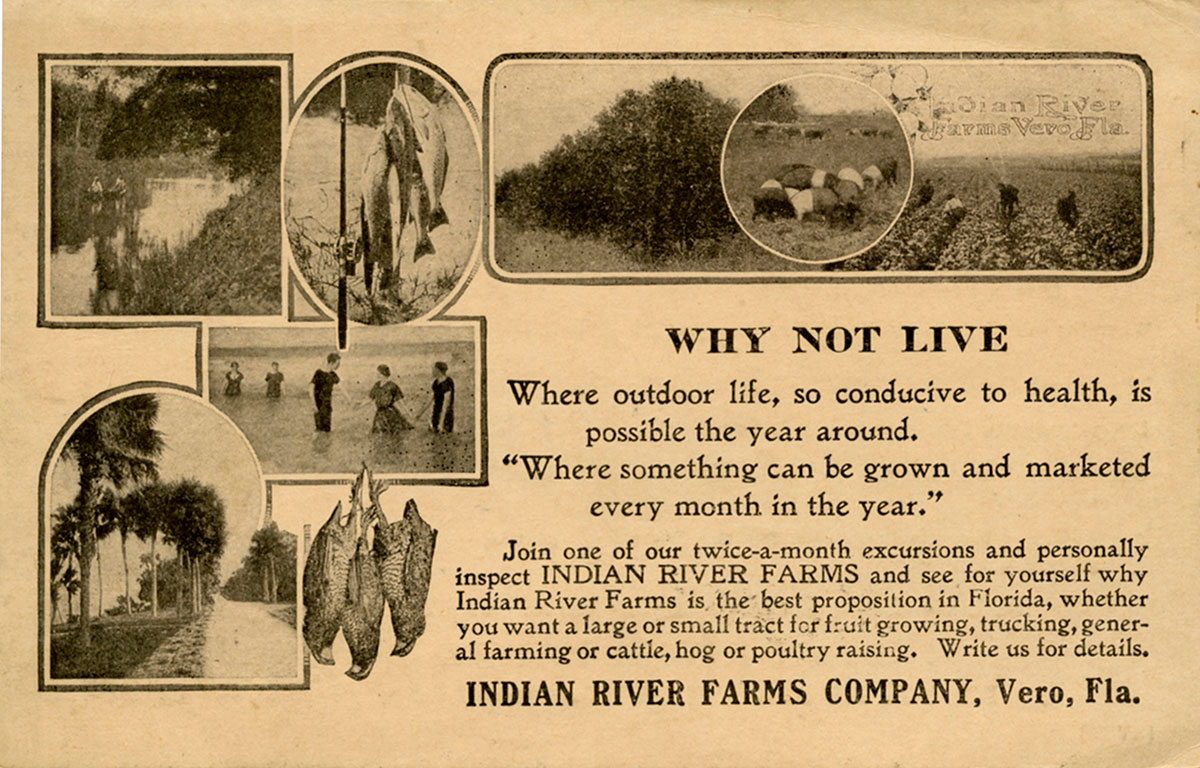

Indian River Farms Co. used promotional material to entice northerners to its land in Vero during the early years of the 20th century. The plats laid out for Indian River Farms would become the heart of the city of Vero Beach.

Small settlement evolves from swampland to Indian River gem known as Vero Beach

BY JANIE GOULD

Like many latter-day retirees who visit towns up and down Florida’s east coast before deciding to settle in Vero Beach, a Vermonter named Henry T. Gifford checked out Titusville, Fort Pierce and the swamps now known as Miami before moving to Vero in 1887, when it was unnamed, unknown and mostly uninhabited.

“He came down here for his health, and there was nobody here but Indians and folks running from the law,” said third-generation native Charles Gifford, Gifford’s great-grandson. “He liked this area, so he went back, packed up everything — horses and everything — and came down on a deck barge. The family pitched a tent on the Indian River to start off with, then built a log cabin.”

Though digs at the Old Ice Age archaeological site show the first humans inhabited the area thousands of years earlier, Henry Gifford is considered the founder of modern-day Vero. He planted pineapples, helped build Dixie Highway and was responsible for lighting the channel markers in the Indian River every night, Charles said. In 1891, he applied for permission to establish a post office and was its first postmaster. The name Vero is often attributed to his wife, Sarah, who suggested the settlement be named Vero, which means to speak the truth in Latin.

The Giffords’ son, Friend Charles, succeeded his father as postmaster and when the Florida East Coast Railway opened a station in Vero in 1903, he became a ticket agent. He farmed 160 acres and planted the area’s first citrus grove.

The Gifford family home, which was built around 1889, still stands at the corner of 20th Street and U.S. 1. PHIL REID

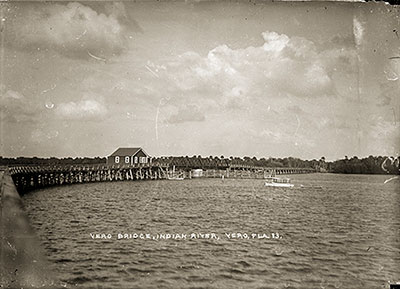

More than 300 cars crossed Vero’s first toll bridge when it was dedicated on Sept. 6, 1920. The wooden swing bridge crossed from present day Royal Palm Pointe to the barrier island. CASSENS COLLECTION, ARCHIVE CENTER, IRC MAIN LIBRARY

HUMBLE BEGINNINGS

The settlement was incorporated by the Florida Legislature on June 10, 1919. Vero Beach is marking the centennial with a yearlong celebration. In 1925, the town’s name was changed to Vero Beach and its boundaries were extended after Indian River County was carved from the northern part of St. Lucie County.

Incorporation gave town officials the legal framework needed to levy taxes and provide services, from utilities to police, to the community of a few hundred. It helped spur Vero’s growth and led to the building of a new school, a few more stores and churches, and in 1920, the first bridge across the Indian River Lagoon. But, regardless of the legislative act, growth would not have been possible if the backcountry had not been made fit for farming and human habitation. It was so swampy that early settlers lived in hammocks and elevated places “where they were more or less safe from water,’’ according to a local newspaper account.

The Vero Press wrote in a Jan. 22, 1926, article on Vero’s beginnings, that the town had appeared it might remain stagnant in its earlier years. It consisted mainly of the post office, a general store, a small school, saw mill and a handful of modest homes.

“The prospects of it ever having much more seemed extremely remote,” the newspaper stated. “During the 30 years since the settlement was started, it had grown almost none at all.”

But this was before Iowa banker Herman Zeuch, who has been called the daddy of Vero Beach, came to town and his company Indian River Farms began to drain thousands of acres of swamp.

At the time, freezes had decimated much of Florida’s citrus crop, but Herman learned that a grove in Vero was unscathed, his grandson Warren Zeuch said in a 2006 interview.

“The grove was at the corner of what is now State Road 60 and 58th Avenue,” Warren said. “It was owned by Mr. Eli Walker and it had survived freezes that wrecked citrus in Florida. Grandfather decided he had to go down and see it. His first trip here was in 1909, and apparently around 1910 he decided to bring an engineer, R.D. Carter, down from North Carolina. Most of the surveying had to be done by boats.”

Indian River Farms Co. bought the land from Walker, drained it by digging a network of canals, and eventually subdivided it into small farms.

“It was 50,000 acres,” Warren said. “Fifty cents an acre.”

PROJECT SPURS GROWTH

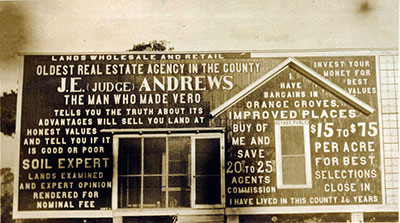

A 1913 ad in an Indianapolis newspaper urged readers to give lots in Indian River Farms to their children and grandchildren as Christmas presents. The company said the warm climate in Florida meant that farmers could raise vegetables and citrus year round.

“No bills for coal, heavy clothing or heartening food,” another ad states. “Cut down on the high cost of living at Vero, Florida.”

The St. Lucie County Tribune dubbed its northern neighbor “Vigorous Vero.” The newspaper also referred to Vero as the modern community of St. Lucie County. In 1917, the Vero Weekly Bulletin announced, “Rice is Another Excellent Vero Crop.” Placards touted the region with the slogan “Grow Two Crops a Year!” and the Florida East Coast Railway made it possible for farmers to ship their produce by rail rather than boat.

The Vero Press said the Indian River Farms drainage project was instrumental in giving the town’s fortunes a much-needed boost.

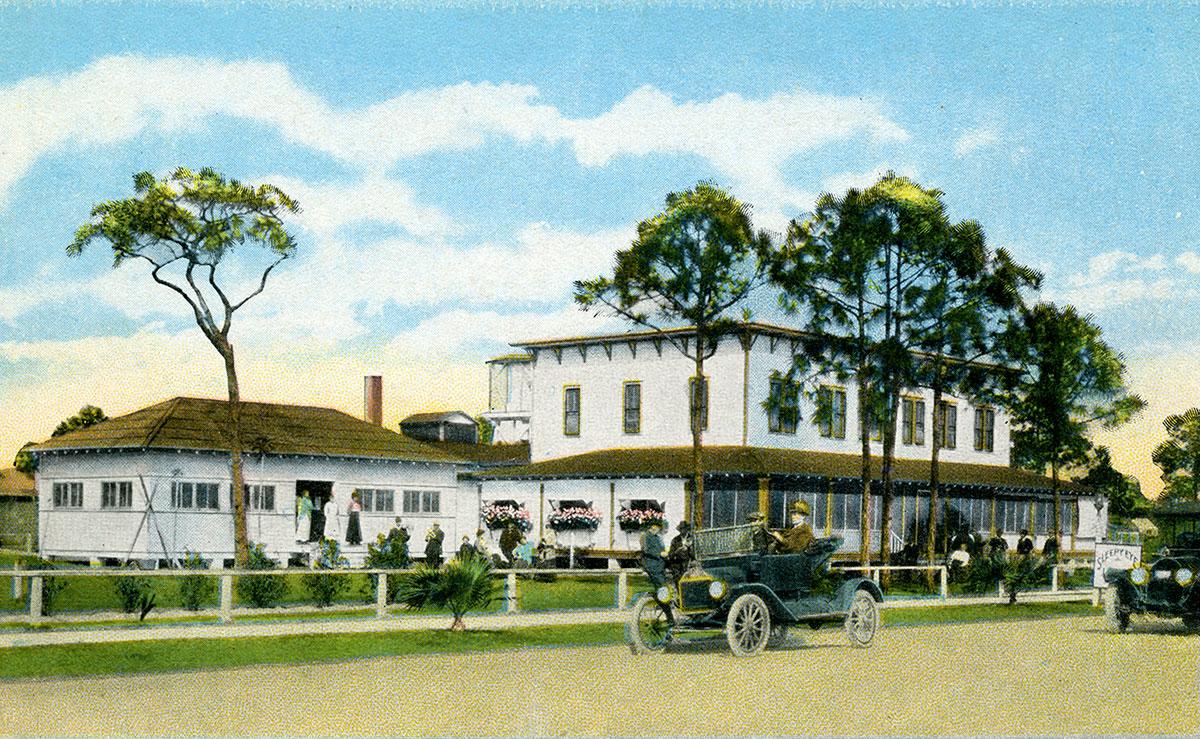

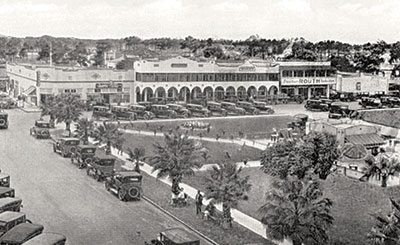

“The little village began to take on new life,” the newspaper said. “A hotel (Sleepy Eye Lodge) was built to accommodate visiting land buyers, and new homes and business buildings began to go up. From that time forward, the town’s progress has never ceased.”

Members of a first-grade class pose in front of the school with their teacher in 1924. HAFFIELD COLLECTION, ARCHIVE CENTER, IRC MAIN LIBRARY

This early photo of the first bridge shows the tenuous connection between the beach and mainland. SMITH COLLECTION, ARCHIVE CENTER, IRC MAIN LIBRARY

PIONEERS COME TO TOWN

The Sleepy Eye Lodge also catered to the occasional traveling salesman, including Waldo Sexton, who sold agricultural tillage equipment. Sometime between 1912 and 1914, depending on to whom you talk, Sexton was in town to give a demonstration at a local farm but delayed his departure because his expense check was late. To pass the time, he explored the area, liked what he saw and during the next few days bought several parcels of land, totaling 120 acres.

Considered to be one of the area’s earliest pioneers, Sexton started selling land for Indian River Farms Co. Within a few years he was raising cattle and citrus along with running a grove maintenance company and a cooperative packing house. He also started the Indian River Citrus League, a dairy farm, an insurance agency and later in life, McKee Jungle Gardens and the eclectic Ocean Grill and Driftwood Inn.

James Hudson Baker, another pioneer, found his way from Jensen Beach when Judge J.E. Andrews of Fort Pierce hired him to build a home west of Vero. The stately two-story house was a landmark for decades on State Road 60 at 58th Avenue. Baker moved to Vero and built numerous downtown structures, too, including the Pocahontas Building, Vero Theatre, Farmers Bank, Sleepy Eye Lodge, and Redstone Hardware and Building Supply Store.

He built a home for his family that was squarely in the middle of downtown, at the intersection of 14th Avenue and State Road 60.

“When he found out he was building the town around his house, I guess he figured it was too close, so he moved it,” said grandson J. Douglas Baker Jr., who grew up in the house.

Vero’s early downtown was the crucible for residential neighborhoods that sprang up nearby, many anchored by churches and schools, including Original Town, home to First Baptist Church, founded in 1912, and Community Church and Church of Christ Scientist, both of which date from the 1920s; Edgewood, site of the Freshman Learning Center and now the city-sanctioned Cultural Arts Village; Royal Park, bracketed by First Presbyterian and Trinity Episcopal churches with the Vero Beach Country Club at its northern boundary; Osceola Park, an officially designated historical neighborhood; and McAnsh Park, with St. Helen Catholic Church at its gateway and the oak-lined Victory Boulevard its main road.

An early post card touted Vero’s Great Steel and Concrete Spillway, part of the development at Indian River Farms. SMITH COLLECTION, ARCHIVE CENTER, IRC MAIN LIBRARY

NEW COUNTY CREATED

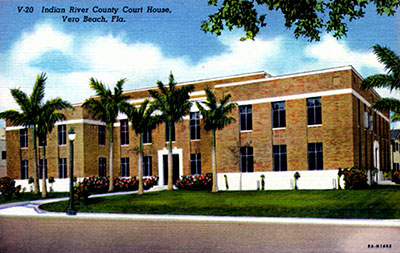

Development got a boost in 1925 when the state legislature created the last two of Florida’s 67 counties — Martin and Indian River — from portions of St. Lucie County. When the St. Lucie County sheriff shut down Vero’s movie theater for showing a film on a Sunday, in violation of local “blue laws,” residents hatched plans to split from St. Lucie. A contingent of civic leaders went to Tallahassee and persuaded the legislature to create the new county.

Later, in a referendum, county voters picked Vero Beach over Winter Beach, formerly known as Quay, to be the county seat.

“Vero won by a large majority of 197 votes,” the Vero Press reported on Jan. 22, 1926.

The newspaper made no secret about how it stood on the issue, telling readers in a headline, “Ambitions of Quay developer given no consideration by thinking voters who have the county’s best interests at heart.”

Newspapers predicted big things for Vero Beach in the mid-1920s, when the great Florida land boom was in full swing, particularly in South Florida. On Dec. 17, 1925, the Vero Beach Press Journal predicted the city would have a population of 35,000 in 1930. Columnist E. J. Sellard called Vero Beach “Florida at its best” and said it was destined to become one of Florida’s big cities.

“When one sees the vast acres representing a potential wealth not to be found anywhere in the universe, and then hears idle prattle about the Florida ‘bubble’ bursting, it’s hard to suppress a feeling of pity for those who heed such insipid propaganda,” Sellard wrote.

BOOM GOES BUST

But a combination of factors, including a killer hurricane in Miami that crippled shipping in September 1926, toppled the land boom and sent real-estate promoters scurrying. Far from hitting the 35,000 mark, Census records show that all of Indian River County had a population of less than 7,000 in 1930. By 1950, the county’s population stood at just less than 12,000, showing a slow but steady increase.

Vero Beach’s barrier island was slower to develop than the mainland. Considered remote and inhospitable and choked with mosquitoes, it was inaccessible to all but the hardiest folks until the first bridge, a wooden structure with an S-curve in the middle, was built in 1920.

Electric power came to Vero’s mainland in 1917, but the beachside was not illuminated until 1930. The Press Journal reported on Dec. 28, 1930, that the city was laying a 1,700-foot, 3-ton cable beneath Indian River Lagoon “all in one piece” to supply electric power to the “peninsula.”

“The cable carries three direct current wires providing sufficient voltage to supply the needs of two or three hundred dwelling houses,” the newspaper reported. “The line will provide much needed service at Riomar, the casino and in Beachland Estates as development in these subdivisions continues.”

Development of the barrier island began with Riomar, a winter colony for wealthy midwesterners. Alex MacWilliam Sr., the builder, had been wounded in World War I and was hospitalized in Cleveland.

“A group of doctors, when he got well, convinced him to go to Vero Beach and develop a winter resort,” his daughter, Helen MacWilliam Glenn, said.

He moved to Vero in 1919 and since there was no bridge, had to transport workers, mules and building materials across the river by barge, Glenn said. He built Riomar’s first five cottages and the golf course. The nine MacWilliam children grew up in a nearby farmhouse. All of them were born at home.

“We had chickens and cows and pigs and horses,“ Glenn said. “We had those Tarzan-style swings on the big oak trees, and of course the ocean was within walking distance. We had a wonderful childhood.”

Alex MacWilliam later served as Vero’s mayor and as a state representative.

“He was always insistent that we have good zoning,” Glenn said.

BEACH DEVELOPMENT SLOW

The city’s Central Beach neighborhoods started to develop later in the 20th century. Its streets south of Beachland Boulevard were named for flowers, while those north of the boulevard were given tree names. In the 1940s, Indian River County native Deward Howard used to hunt bears and wild hogs in Central Beach. He also took to the woods in search of cabbage palms, and never had to look far to find them.

“They were plentiful,” Howard said in a 2007 radio interview at his Central Beach home. “I mean they were everywhere. We just went after the cabbage for special occasions. It’s a lot of hard work getting those things. Now, a bear, he can get those things with his hands. A bear can get one by himself!”

With the notable exception of Sexton’s Ocean Grill restaurant and Driftwood Inn, there wasn’t much business on the beachside until mid-century. Ocean Drive was a shell road bordered by palmettos on the west side when businessman S.B. Taylor built four cottages and a bathhouse on the ocean and named the complex Taylor Town. He later added a swimming pool and motel, the Seahorse Inn.

“There were no shops of any kind,” his daughter, Mary Young Johnson, recalled in a radio interview. “You could go up to the Ocean Grill and get an ice cream.”

Johnson said her father bought the land by paying the unpaid taxes on it during the early years of the Great Depression.

Taylor Town is long gone. Gloria Estefan’s stunning multimillion dollar hotel, Costa d’Este, now sits on the property.

“Daddy knew the minute he came to town that he should buy oceanfront property, that it would someday be very valuable,” Johnson said. “He would not be surprised with what’s there now.”

Longtime beachside business owner Callie Corey said in a radio interview there were no schools and few homes on the barrier island in 1956, when she and her late husband, Luke, moved to Vero Beach with their young children to operate Corey’s Pharmacy on Ocean Drive.

“It was windy and no one was around and we thought it looked like a very desolate place, but the next day looked better, so we stayed,” Corey said.

Community leader Alma Lee Loy said the city is special because of those who came before.

“They had so much vision and worked hard to build this city,” she said, “and they were always willing to help each other. If the Methodists were building a church, the Baptists went over to help, and vice versa.”

PRESERVING HISTORY

Another thing that makes Vero Beach distinctive, she said, is its restriction on building heights. Indian River County set a three-story height limit in the 1950s. In 1968, after a pair of 14-story oceanfront condos rose in Vero’s beach business district, city voters agreed to reduce building heights in the city from five stories to three.

Groups such as Main Street and the Cultural Council of Indian River County are working to enhance the historical downtown. Nearby residents are also seeking ways to preserve the historical qualities of Original Town and Osceola Park. The city has adopted a historical preservation ordinance, and preservationist Anna Brady has updated historical resource surveys of both neighborhoods.

“It is incredibly important for future generations to have authentic history that they can see,“ Brady said.

With decades of well-planned growth, Vero Beach is no longer the remote backwater of a century ago. The Vero Beach Municipal Airport, founded in 1930 as a fuel stop for Eastern Airlines, has become a hub for business and industry, notably Piper Aircraft, the only general aviation manufacturer to offer a complete line of aircraft, from trainers to high-performance turboprops. The airport still offers regular air service by Elite Airways. The Los Angeles Dodgers’ spring training facilities, vacated when the team left in 2008, have become the Historic Dodgertown Conference Center. The city boasts countless amenities, such as Riverside Theatre, the Vero Beach Museum of Art, and an array of well-maintained parks, beaches and ball fields.

If Alex MacWilliam could see what the city has become, “I think he’d be very pleased,” Glenn, his daughter, said.