Backus in the light

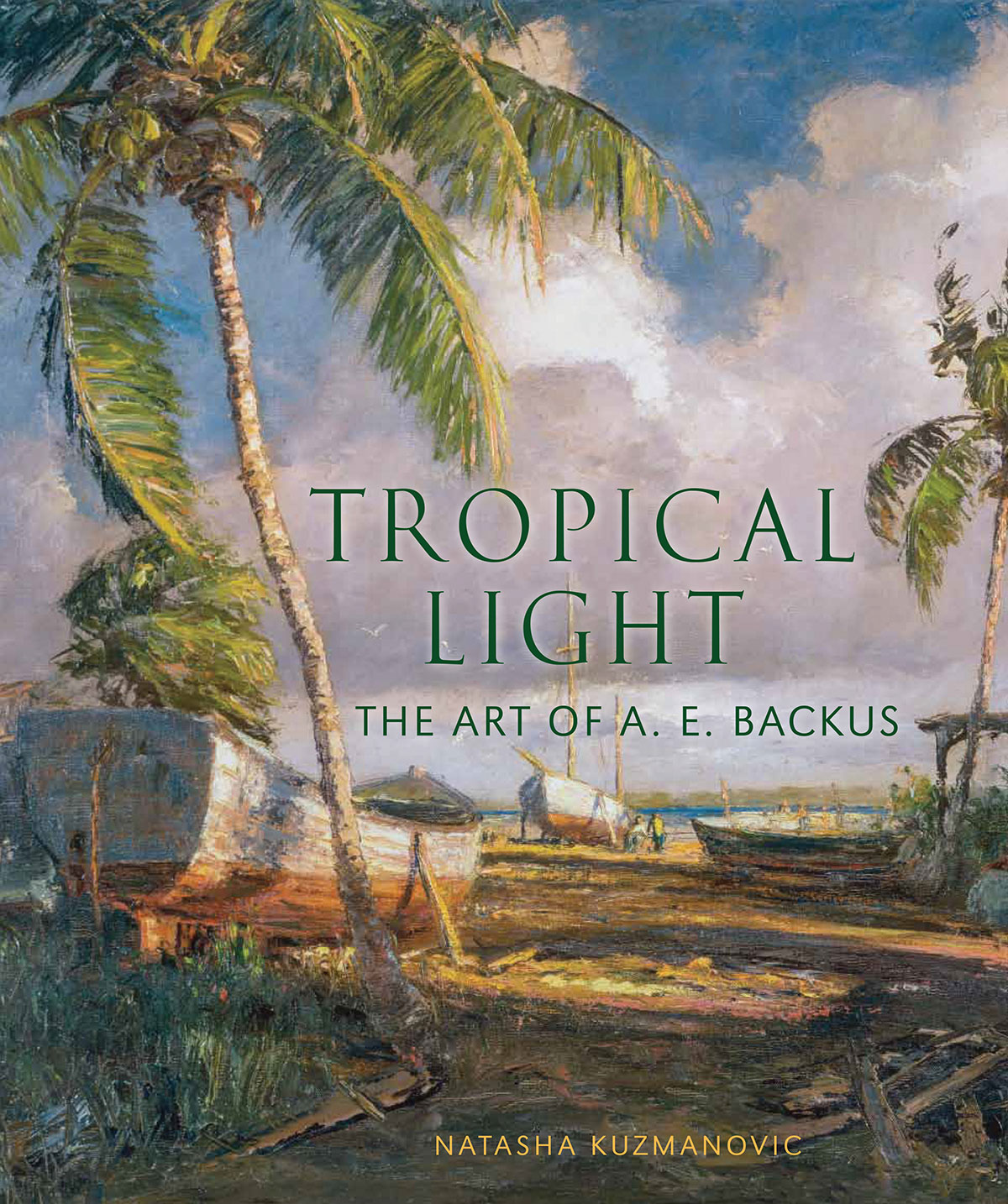

Backus’ The Boat Yard, which he painted around 1951, graces the cover of the new book by Natasha Kuzmanovic, an art historian and conservator. The painting is in the Vartanian Collection.

Book shares art, life of Florida’s pre-eminent landscape artist

BY JANIE GOULD

Tropical Light: The Art of A.E. Backus, the new book about the renowned Florida painter who lived in Fort Pierce, stands as a virtual gallery of his work with beautifully reproduced images of his landscapes, seascapes, portraits and small-town scenes on nearly every page.

Readers could spend hours poring over the visuals and then, as I did, return to them again and again to seek something new. Some of the most compelling images are of his lesser-known works, including scenes he painted in Jamaica, portraits that he did of people named and unnamed, murals and his later ventures into semi-abstractionism.

The book, written by Natasha Kuzmanovic, an art historian and conservator, and published by the A.E. Backus Museum in association with the Vendome Press of New York, will undoubtedly grace the coffee tables and waiting rooms of Backus fans throughout Florida and beyond.

Much has been written about Backus, including the 1984 book A.E. Backus: Florida Artist, by Olive Dame Peterson, whom the author cites, but this book obviously aims to be the definitive study. In many ways, it succeeds admirably. Art historians, Florida history buffs and others will find much to ponder in the section on artistic influences on Backus.

The section on Backus’ patrons also has interest. A wide array of Florida political and business leaders, including former Sen. George Smathers, Boca Raton banker and Florida Atlantic University founder Thomas Fleming, and former Govs. LeRoy Collins and Bob Graham who wrote the foreward, purchased Backus paintings. The book states that men were especially attracted to paintings of rural Florida — backcountry and river scenes — because they could hang them in their office and imagine they were hunting or fishing rather than working.

Albert Ernest Backus was born in Fort Pierce in 1906 to George Tay Backus and Josephine Sheridan, who moved from New Jersey at the end of the 19th century. The section on Backus’ biography draws upon numerous sources gained from personal interviews and the written record. Unfortunately, it’s written in the style of an academic research paper. Most of the direct quotes, except those from Backus, are not attributed in the text. Instead, they are footnoted, requiring a reader to go to the bibliography at the end of the book to find out who said it.

For example, Backus’ well-known lack of racial prejudice was described in the book as having had an impact on the community, influencing “an awful lot of rednecks into being a gentler, kinder bunch of people.”

That provocative quote had no attribution in the text, only a footnote. I thumbed to the back of the book and looked up footnote No. 99 to find that the comment was made by Backus’ business manager, Don Brown, in a 2012 interview.

The book also had no full attribution for an erroneous claim that the artist made a pet of wildlife. “He had a skunk — a wild skunk — that lived in the studio in the late ’60s- ’70s. Never sprayed anybody.”

In an effort to find out who said that, I referred to the footnote, but got only a last name, Neilson, and Backus Magic, with a page number. I realized it may be a subsequent use of the source, but I couldn’t find an earlier reference in the bibliography. Telling the reader who said what right in the text would have made the narrative a lot more readable.

Backus’ fondness for rum was never a secret and his generosity to aspiring artists and others in need was well known. Both matters are explored in the book. Backus, who died in 1990, was a colorful figure and the book could have benefited from more funny stories about him, warts and all.

But no one is going to buy the book for the text. The color plates are awesome and as I looked at them, again and again, I tried to pick a favorite. His impressionistic-style scenes represent such a departure from the backcountry landscapes for which he is best known. Tenor Man, his 1946 portrait of an unidentified musician, astounded me with its color and shading, as did Seminole Woman, painted around 1939.

Harvesting Florida, depicted in a two-page spread, shows Seminole women picking the state’s winter vegetable crops,such as tomatoes and beans, while a man swings a machete toward a cabbage palm. Baskets filled with the bounty, including heart of palm, stand in the foreground. The dramatic panorama, which includes a stylized map of Florida, reflects the influence of the Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, as the book states.

Backus also drew inspiration from work of the French Impressionists. The text delves into this influence, but nothing says it better than two works displayed on the same page: Backus’ Pond at Edenlawn, which he painted about 1939, and Claude Monet’s 1906 work, Water Lilies, shown in a detail view.

Tropical Light: The Art of A.E. Backus is a visual feast for the many admirers of this notable native son of Fort Pierce.

TROPICAL LIGHT: THE ART OF A.E. BACKUS

Author: Natasha Kuzmanovic

Published by: A.E. Backus Museum, in association with The Vendome Press, New York (2016)

Price: $75; available at the museum’s store