An original snowbird

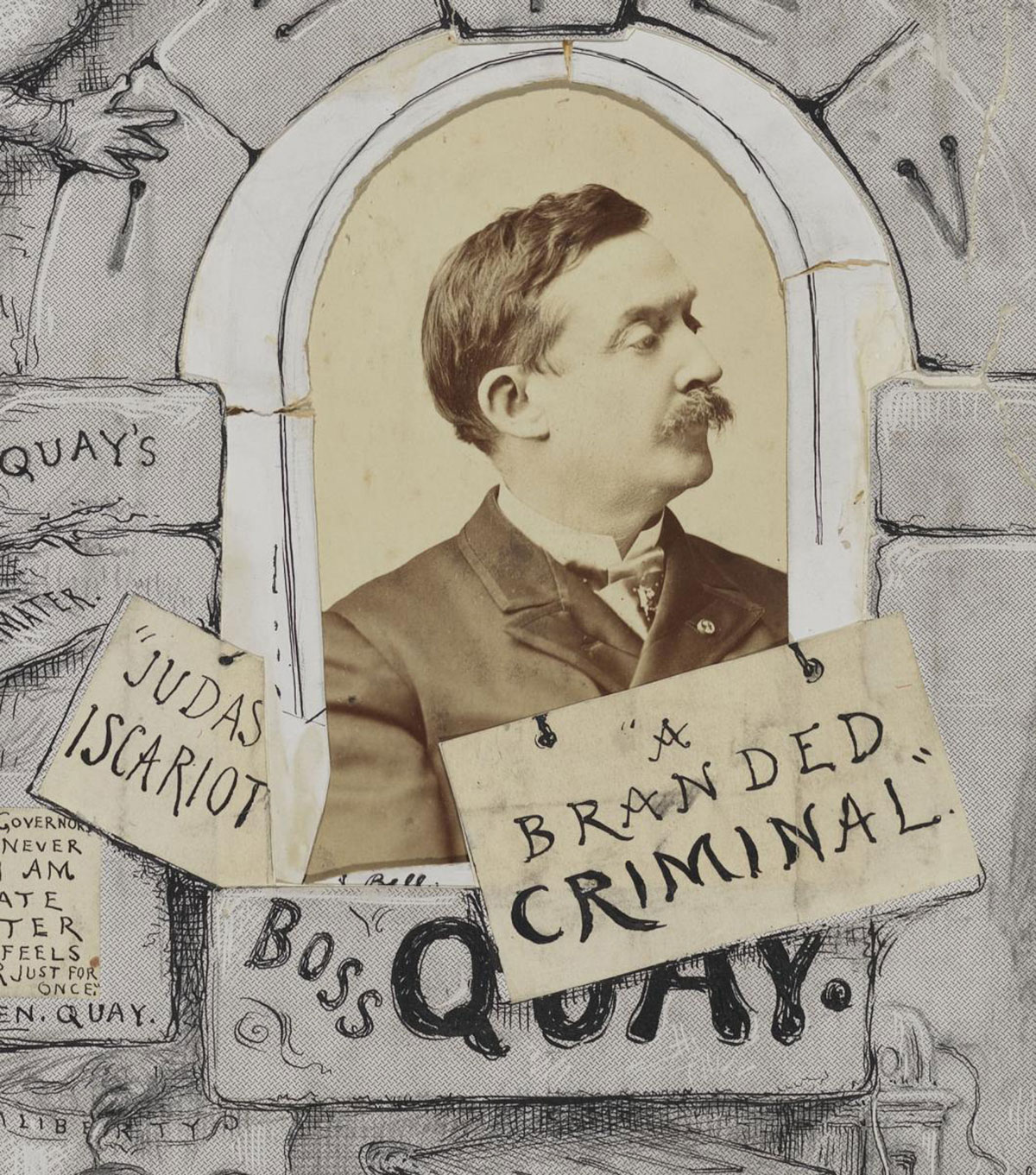

Sen. Matthew Quay, who was suspected of using public funds for his own profit, was often vilified by political cartoonists in major newspapers. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS PHOTO

Gilded Age political boss left mark on his adopted Treasure Coast home

BY JEAN ELLEN WILSON

The telegram from the White House addressed to Honorable M.S. Quay at St. Lucie, Fla. was delivered on Feb. 3, 1904. It read: “Telegram received. Matter has been arranged exactly as you desire it. Theodore Roosevelt.”

What manner of man residing in the tiny village of St. Lucie on the banks of the Indian River in frontier Florida enjoyed such favor from the president of the United States?

He was Matthew Stanley Quay, also known as Boss Quay, a Gilded Age headline maker. A Republican senator from Pennsylvania, he was the original snowbird on the Treasure Coast.

The area’s history would have been different had it not been for Matt Quay. He discovered a paradise that caused others to come and become part of what the area is today. A goodly number of U.S. senators as well as many Pennsylvania officials discovered the Indian River area when they accepted his hospitality.

For example, state Sen. James P. McNichols assisted the Catholic church in its development in St. Lucie County. The church was named in honor of his first wife, Anastasia, as McNichols was able to influence the settlement of some pioneering Catholic families in the area, including the Forget and Guettler families.

Rep. William Vare was another Pennsylvanian who came in Quay’s wake. He was one of the consortium that built the St. Lucie Club and would later take possession of the property. Vare’s descendants, the ranching Peacocks, sold their vast acreage to developers who would create Port St. Lucie.

CAME SOUTH FOR HIS HEALTH

Quay maintained residences in Beaver, Pa., and Washington, D.C., but he came to the Indian River for his health — he had inherited the family weakness of the lungs. His mother, father, brother and sister all died of consumption and he always lived with the probability of the same fate. He also came for the fishing — Old St. Lucie was directly across from the original Indian River Inlet, at that time one of the sports world’s destinations for tarpon fishing.

Before building their own quarters, the Quays boarded at the St. Lucie House, which for years after the Civil War was the southernmost point of nurture for fishermen, hunters and explorers of what was then a wilderness. It was operated by the Paine family — Jim and Tom with their mother as cook.

Emily Bell, in her My Pioneer Days in Florida, recalled the vacationing Quays in their early years on the river: “They came to our house and we gave dances ... We would invite the guests and send ox teams for them to come down ... Dick Quay loved to dance what he called a cracker breakdown, and was a sport right. He paid the fiddler and the man who beat the strings. Ben Souy and wife always came, and he would dance till the last minute, then sing ‘We Won’t Go Home Till Morning,’ and it was three in the morning many times when they would leave.”

A New York World reporter who came to St. Lucie described the Paine place thus: “The cottage where they board is back from the water about one hundred yards, and is a private boarding house and hotel combined, there being no other inn in the village. St. Lucie contains about one hundred inhabitants, mostly fishermen and orange growers.”

Once, when boarding at Paine’s, Quay was joined by a raucous party of fishermen on board the yacht Minnehaha, whose log related how the senator taught them a new game — poker. Indeed, the accusation of his enemies that he was a gambler was all too true.

A reporter for the Cincinnati Tribune recognized the connection between his gambling and his politics. “Admittedly,” he wrote, “Quay is a gambler and what is considered reckless in the card player is the virtue of the man who trusts his life to battle ... Play, play, play up to the highest notch of risk constitutes his chief passion. Like all such men, he frequently shows the greatest sagacity, and has no fear of an adverse majority... any more than he would fear the opinions of dozens of men behind him watching his hand full of cards …”

WROTE HOME FREQUENTLY

Quay wrote faithfully to his wife and children while vacationing in Florida from 1885 to 1904. He wrote about his health, he gave fatherly advice to his daughters, he recounted the hunting and fishing successes of himself, his two sons, and a parade of famous visitors. He reported on domestic arrangements, the mosquitoes and the food. Buried in the correspondence are gems of information about what was once a part of Brevard County.

In a letter dated Jan. 24, 1886, the senator told his wife, Agnes, “The cold weather has killed the fish. They are lying dead by millions all along Indian River for 200 miles.”

Excerpt from a letter dated Nov. 25, 1890:

“We have been here since the 10th fishing a good deal and hunting some. We have caught 31 tarpon. ... The tarpon were taken with hook & line by moonlight in the inlet. ... Mrs. Paine has been sick but is better. She is frail and looks feeble. Jim and Tom are just the same. Argyle has been helping about the house. Dick bought five acres from Tom and is building a big frame roomy home upon it. It has eight large rooms 15 by 20 an attic a two-story verandah on three sides and fronts on the river. There are to be a dock where the steamer can land a boat house a naptha launch... sailboats too so you can make yourself comfortable when you next come here. The frame is up and the house will soon be under roof.” It was signed by his usual “Your aft Father.”

In a letter dated March 10, 1891, the senator apprised Agnes of St. Lucie affairs: The launch is here with ‘Coralie’ in large letters on each side of the prow and is a beauty (named for daughter Coral). Dick’s house is getting along nicely and is going to look well from the outside. We were apprehensive it would not. When it is completed the lot will have to be fenced and beautified and I guess Annie will have to come down with servants next summer and get in the furniture and start the machine running. It is an exceedingly good house for this country. Mrs. Paine has been very sick ever since we came & I am fearful will not get well. Of course matters are out of gear and Jim has to get along as best he can. The table is not as good as usual. If she is taken away I don’t know what they will do. Some days I am much better others in the dumps ... I wish Annie would get me a hundred good cigars and send them here by registered mail am about out.”

LIFE ON THE INDIAN RIVER

He reported in September 1892: “The weather is warm ... at 8 or 9 A M a cool sea breeze springs up and blows steadily all day to fly away after sundown. There is bright moonlight and everything is as pleasant as can be except for the mosquitoes ... Some mornings there are none in the upper balcony, and we sit up there in the breeze in the moonlight. Two of the hammocks are strung up there and are comfortable in the afternoon. We have wire screens in the sleeping rooms mosquito nets up and get along very well after we go to bed. The fruit except the oranges are ripe and we are feasting on mangoes, sapodillas, cattley guavas. The mangoes I had last year were spoiled. The cocoanut trees are all living. The yard was grown up three feet in grass which I have had cut off. We are getting fresh meat and ice from Titusville twice a week.”

He reported they churn their own butter and have plenty of fish to eat. Other items on the menu regularly were deviled crabs and green turtle. The Summerlins supplied the chickens and eggs and oysters.

“If the cholera comes the best place is right here,” the senator wrote in one letter. “There never has been a case of cholera or yellow fever or any epidemic disease on the Indian River.”

Quay, after being elected to his second Senate term, was in St. Lucie in the spring of 1893, accompanied by the whole family. Improvements to the estate included a well and a windmill. Returning in November to view the damage of a hurricane, he wrote: “The telegraph lines are down to Fort Pierce and the only cocoanut trees that have survived are those in the nursery. Clarence Summerlin is fixing up the newly fenced yard and “playing coachman.”

Toward the end of November, Quay informed Agnes that the railroad would reach St. Lucie within the next three weeks. “The sick god is behaving,” he assured his family and he is getting “fat as an alderman.”

Quay and his party made the trip south in Henry Flagler’s private car in the spring of 1895. After the back-to-back freezes of 1894-95, all the plants around the houses had died except the century plants and Spanish bayonets. There were no oranges, grapefruit, bananas or vegetables and the table suffered.

TRAVEL BECAME EASIER

Evidently, the Quay house was named, and the first letter written on Kilcaire letterhead was mailed from St. Lucie in 1897. The private car that uncoupled practically at the back door of the estate allowed the Quay family and friends to visit more often. They were in residence in January, March, August, September and November. In the last month, the senator chartered the schooner Elizabeth C. Lawrence, with Capt. Benjamin Hogg, and went out to the snapper banks to fish.

Although held in high esteem by his St. Lucie neighbors, Quay was, nationally, definitely controversial. But controversial in public life meant that opinion as to character or actions was sharply divided.

Typical of his opponent’s view: “The boss unites shrewdness and audacity with executive ability.” His “profoundest conviction is ... that the Decalogue and the Golden Rule have no place in politics. His power is based largely on the prostitution of public patronage ... with the single object of maintaining his own ascendancy over the henchmen who do his dirty work in managing primary elections and controlling nominating conventions.”

His supporters expressed an entirely different take: He exhibited, one wrote, a “familiarity with natural men, and want of all artificiality and snobbery ... a stunted looking man of no style, his eye is a little oblique, his shape like a three-cornered nut, and as he drinks whiskey he never has much complexion... a man of more reading and information ... than the editors of the Evening Post and probably has a better library than any other man in public life.”

Another voice assessed his political performance: “Mr. Quay is a plain, simple, modest and kindly man ... with a genius for the organization and control of men in masses ... Without prating about honesty he has this essential of the highest integrity that he meets every obligation and keeps his every word. He has a courage which never flinches, whether in war or politics.”

He was a learned man who corresponded in Latin with Pennsylvania Gov. Samuel Pennypacker. The governor visited St. Lucie, where one might imagine him sitting on the upper balcony conversing, according to Collier’s “on topics of the day, Like Moses, Plato, Socrates, Himself and Matthew Quay.”

POLITICAL BEGINNINGS

Quay, a Civil War veteran and a Medal of Honor recipient, turned from journalism to politics and worked his way up until he became the junior senator from Pennsylvania in 1887. The next year he was chairman of the Republican National Committee, then a much more powerful position. With the machinery of the state and national party in his hands, Quay exercised his power as described by a disappointed Pittsburgh office-seeker: “If one ... ventures to question the orders given, Mr. Quay calmly inquires whether he ever expects to come back again, and whether he proposes to run his canvasses in the future with aid from the State and National Committees, or without it.”

For the next 19 years, various combinations of avowed foes and turncoat friends fought to topple him; reformers attempted to wrest power from his grasp and destroy his political machine. Often his political survival was in doubt; there were times he survived by a very slim margin. He was indicted, arrested, beaten at the polls, attacked from the pulpit, criticized in the press. He endured to make two presidents and to serve three terms in the Senate.

After every major campaign or at the recurrent onsets of la grippe, Quay would retreat to St. Lucie to recover. He called it “the Seminole cure.” He was castigated by his adversaries for his poor attendance record due to spending so much time in Florida.

FACED NUMEROUS CHARGES

As the Gay Nineties began, The New York World published an expose laying out Quay’s alleged crimes, which included bribery, cowardice, using government funds for personal expenses, embezzlement, and chronic drunkenness. Quay stoically bore the brunt of all the bad publicity in the wake of the paper’s attack, refusing to address the accusations. As friend and foe alike wrung their hands, the boss fished on the Indian River.

Over the years, he would refuse to talk to reporters about politics, but he would talk about fishing: “The last tarpon I caught ... weighed 112 pounds. I hooked him with a fresh mullet for bait ... he dragged the boat for three miles up Indian River and jumped ten feet out of the water, his silver scales shining... in the morning sun. It took us just two hours to bag that fish, and then both my boatman and myself were too tired to fish any more that day.”

Another time he related his The Old Man and the Sea story: The tarpon on his line was tiring when “Fifty feet away I noticed a huge fin cutting the still water ... The tarpon, too, as if he had human feelings (he certainly exhibited human fear) soon knew that an immense shark was around and that a new danger threatened him ... The great shark, intent on a full supper, circled swiftly around both boat and fish ... I had the fish within 10 feet of the skiff and he came belly up, bleeding at the gills plentifully. Suddenly clearing the water the big man eater came like an arrow. There was a splash — more blood on the water — the tarpon was lifted clear out of the river, and the spot where a live fish had been was crimson with blood ... There was nothing to say. I ordered Ben Souy to sail the boat toward shore, and we got out and got a good supper.”

FRIEND TO NATIVE AMERICANS

Native American rights was the one issue that Quay, whose great-great-grandmother was an American Indian, supported consistently and without self-interest. Margaret Leech, in her book In the Days of McKinley wrote: “Quay was up to his elbows in the treasury of Pennsylvania, but he was not a boodler of the ordinary stamp. He was the Indian’s friend, adopted by certain tribes, and initiated into their rites. He was an accomplished linguist, and a student of military and religious history; and he carried an Elzevir Horace, along with Pennsylvania, in his pocket.”

Quay assisted the Seminoles in his adopted state of Florida. There must have been many instances of good will toward the Seminoles from whom he often purchased venison. Those on the record included his paying the expenses of Tommy Jumper who needed treatment at the hospital at St. Augustine in 1901. He presented Tom Tiger with a silver mounted rifle. He was visited at St. Lucie Village by a pair of American Indian chiefs from the West who were treated as hospitably as his close friends.

As a result of Quay’s efforts in the Senate, the national budget for 1894 included $20,000 for dredging work in the Indian River Inlet. In September 1903, the Star carried this news: “The digging of the Fort Pierce cut by Senator Quay under the able supervision of Capt. Ben Sooy, of St. Lucie, was brought to a sudden termination Friday, when old ocean decided she could do more work in a minute than those workmen would do in weeks, so she opened her flood gates and cut a channel a great width in a turnkey. The water in the cut is teeming with thousands of fish, coming into the river which bids fair to make a prosperous winter season for those enjoined in this popular industry. Hurrah! For Senator Quay and Capt. Ben Sooy.”

He also offered assistance to local pineapple growers who were interested in putting a duty on foreign imports. In fact, he was so amenable to aiding local interests that he was affectionately referred to as “Florida’s third senator.”

PAID FOR RAILROAD WORK

Quay was responsible for a railroad station in St. Lucie Village. He broached the subject of the need for one with Florida East Coast railway executives who asked him to choose a site. He chose a location, the station was was built, and to his surprise, was given a bill for the job — $1,500. He paid it.

He could be counted on to support local causes. For example, he gave $100 toward the building of the Episcopal Church and donated to the children’s Christmas fund. He was often accompanied to St. Lucie by a Philadelphia physician and must have arranged for the doctor to extend his service to locals as it was reported in the local news that Dr. Fox removed a cataract from the eye of Mrs. S.A. Bell.

Today, at the corner of a lane in the village, there is a sign: “MATTHEW QUAY WAY.” It is next to a house that was built in 1899 by Richard Quay, the senator’s eldest son and right-hand man. An earlier house, built in 1890 when Richard purchased the first of three parcels of land from Tom Paine, burned in March 1963. When the popularity of St. Lucie outgrew the hospitality of the two Quay houses, a group of Pennsylvanians built the St. Lucie Club, similar in architecture to the larger Quay house. This building also survives. What is no more is the palm-lined walk that led from the club to the railroad siding where the private cars of Gilded Age dignitaries waited to take them away.

FACED BANKING SCANDAL

The year 1896 brought the most resounding challenge yet to Quay’s career. John Wanamaker, Philadelphia department store tycoon, led the opposition. “You voted down black slavery, why not vote down slavery to one white man, even though for a quarter of a century he has been your master?” he challenged.

On March 24, 1898, the Peoples Bank of Philadelphia failed and its cashier, John S. Hopkins, longtime financial errand boy of Quay, went home for lunch and committed suicide. Quay’s opponents pounced on a note from the senator found in Hopkins’ desk: “If you buy and carry a thousand Met for me, I’ll shake the plum tree.” The scandal caused deep rifts in the Republican hard core. Later in the year, Quay was arrested and charged with being involved in the bank scandal and misusing public funds. His pending trial did not keep him from the Indian River.

In January 1899, the Pennsylvania Legislature convened to elect a senator — in those days the office was not decided by popular vote. Between Jan. 17 and April 20, no candidate garnered enough votes after 79 ballots to claim the seat. While the balloting was going on, Quay was tried and acquitted of all charges. As the legislature adjourned without choosing a senator, the governor appointed Quay to the office. The Senate opposed the appointment. The Senate voted 32-32 in April with the nays avowing that the founding fathers never intended to give the state executive the power to choose a senator.

It came about that it was up to George Graham Vest, a Democrat and the senator’s good friend and recent guest at St. Lucie, to break the tie and he did, voting no. Next day, Quay received a note in which the Missouri senator wrote that he “suffered more than in all my public life over this vote ... I am and will always be your friend, and sincerely pray that you will triumph over all your enemies, as I believe you will.”

For the next session of Congress, Pennsylvania had only one senator in Washington.

SUPPORTED ROOSEVELT

In 1900, there was no doubt the Republicans would nominate President William McKinley for another term. The only issue at the convention was who would be the vice presidential candidate. Delegate Quay, against fierce opposition, used his clout to force the nomination of Theodore Roosevelt as McKinley’s running mate.

“Don’t any of you realize that there’s only one life between that madman and the Presidency?” protested one of the president’s advisers. When McKinley was assassinated in 1901, the madman became president and that was how telegrams from the White House arrived in tiny St. Lucie.

In January 1901, the Pennsylvania Legislature returned Quay to the Senate and as the celebration of his swearing-in continued, Quay slipped away to have a quiet dinner with his old friend Vest.

By the end of the month, Quay was recuperating from an attack of consumption at Kilcaire. He wrote Agnes: “I feel better today than I have since I took the grippe but am still very weak. I suppose the excitement kept me up until I came here. My stomach is better I believe it was nearly ruined by medicine and that whiskey & champagne made it worse instead of better.”

The senator’s interest in the West and statehood for New Mexico, Arizona and Oklahoma distracted his attention from fishing. Oddly enough, there is both a county and a town in New Mexico named Quay in the boss’s honor, but the only place he is remembered in Florida is the lane in St. Lucie. In Florida, Woodley, which was established in 1894, became Quay in 1902 — then became Winter Beach in 1925.

On Feb. 16, 1904, Quay wrote to his son Richard: “In the week ending yesterday noon I lost something like one pound and a quarter. A week ago I weighed 144 ½, yesterday 143 full — a little over. There is no mistake for I was weighed on the same scales at the same time of the day and with exactly the same clothing. This cannot go on very long. Say nothing about it. I thought you ought to know it.”

Matthew Stanley Quay died in Beaver on May 28, 1904. His will was filed in St. Lucie County.