An epic tale of survival

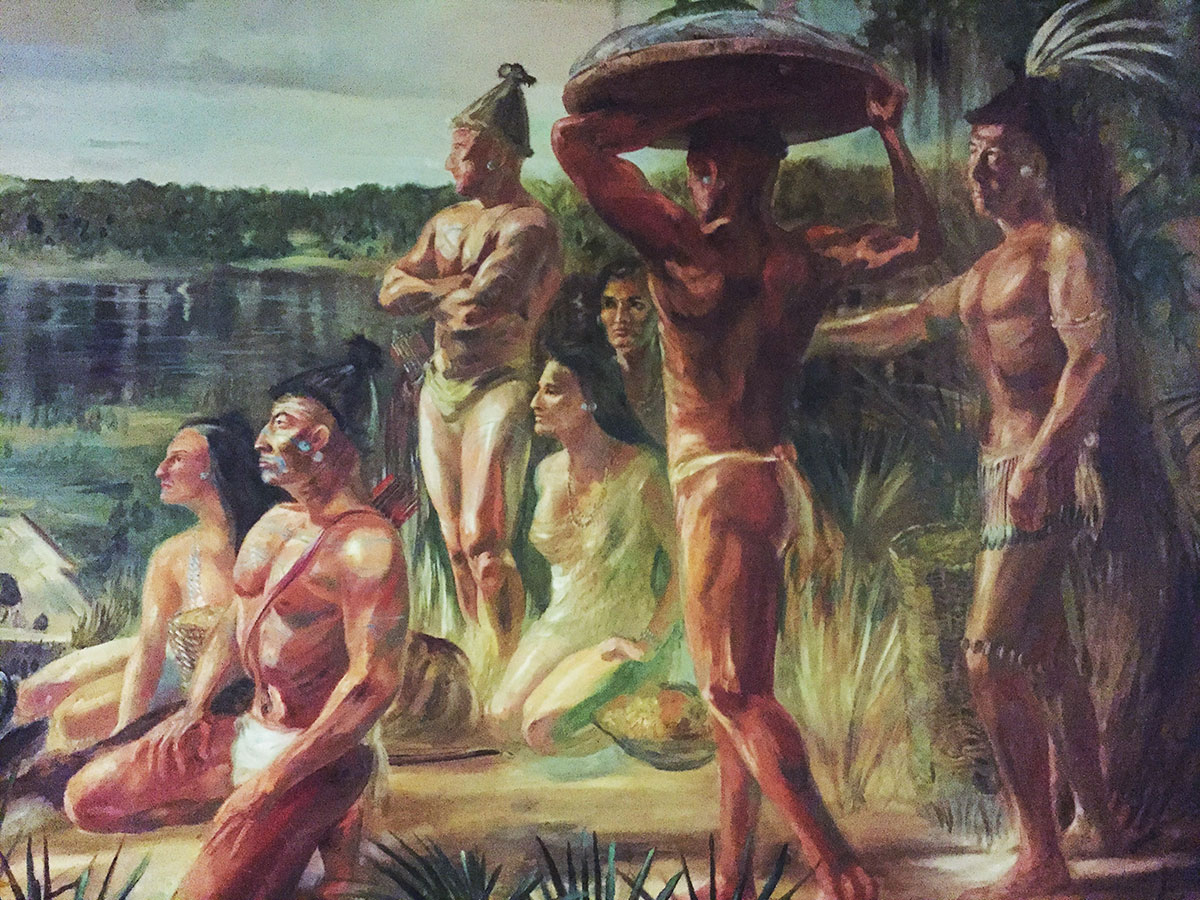

Survivors of the Reformation were captured by Indians similar to these depicted in Jacksonville Public Library’s mural Ribault’s Landing by Lee Adams. RICK CRARY PHOTO

Journal describes brutal capture, rescue of British castaways from coastal Indians

BY RICK CRARY

Of all the ships that foundered off the Treasure Coast through the centuries, the one remembered best is the Reformation. After it ran aground on Jupiter Island 320 years ago, a survivor wrote a book that became an early American classic: God’s Protecting Providence. We know it better today as Jonathan Dickinson’s Journal. An 11,500-acre state park in Hobe Sound was named in honor of the author, but it was an elderly evangelist’s story that made the shipwreck famous. Robert Barrow’s quest to survive Florida’s unforgiving wilderness captured a bygone public’s attention.

For a couple of centuries after the discovery of Florida, the Treasure Coast was little more than a shadowy land of danger, a place where unlucky travelers shipwrecked and disappeared forever. Sailing ships were no match for random gale-force storms with surging waves, and to travel the ocean’s superhighway ― the Gulf Stream ― was to roll the dice and face a chance of dying on the reefs.

The risk of drowning was very real, but making it to shore could be much worse. Stone Age natives, whose palm-thatched towns and villages lined the coast, were said to be bloodthirsty barbarians. According to a Spanish colonial governor’s report in 1574, the Indians sacrificed shipwreck victims and used their severed heads in pagan ceremonies.