THE FINE ART OF FRIENDSHIP

An upcoming exhibition at the Backus Museum highlights the bonds between artist ‘Bean’ Backus and publishing magnate ‘Kip’ Kiplinger

BY RICK CRARY

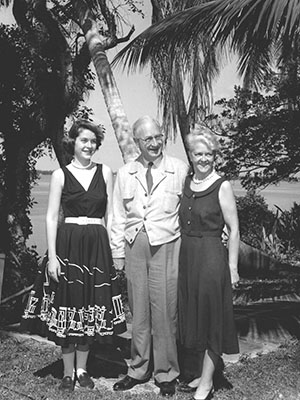

The friendship of two of the Treasure Coast’s most notable historic personalities, A.E. “Bean” Backus and Willard Monroe “Kip” Kiplinger, is being celebrated in an exhibit titled Kindred Spirits: Paintings and Letters from the Kiplinger Family Collection. The exhibition runs from Nov. 17 through Jan. 7, 2024 at the A.E. Backus Museum and Gallery in Fort Pierce.

“W.M. Kiplinger and A.E. Backus were very different individuals yet shared values whose effects continue to resonate today,” said J. Marshall Adams, the museum’s executive director. “Both believed that investing in your community was a responsibility to develop and improve future generations. Kiplinger knew how to use his patronage to both individuals and institutions for positive ends, and Backus understood how the life of an unselfish artist could reap dividends for years to come in the lives of others.”

ROAD TO FINE ARTS

Backus had the magic touch of a master, which Kiplinger saw right away when the two men met in the mid-1950s. Many others had recognized the artist’s exceptional talents in earlier decades. Backus had sold his first painting while he was still in high school.

In 1925, when he was 19, a family friend sent him to New York for the summer to obtain formal training at the prestigious Parson’s School of Design in Greenwich Village. Backus returned there to study for one more summer in 1926. Back home in Fort Pierce, he used his training primarily for painting movie posters for the Sunrise Theatre.

Backus credited Don Blanding, a nationally known best-selling poet, with giving him a push to give up commercial sign painting to focus on fine arts. Blanding, who was a painter, himself, was also the third husband of Dorothy Binney, daughter of Edwin Binney, the inventor of Crayola crayons. Dorothy and her family were already fans of Backus’ earliest works.

MEDIA GIANT IN STUART

By the time Kiplinger met Backus, the artist had won a fair amount of recognition, but his career had yet to soar. Kiplinger, a man of national acclaim, had founded his own media empire centered in Washington, D.C. His company had a 10-story building as headquarters, just three blocks from the White House. Businessmen and bankers all over the country depended on insights he offered them in publications like his famous Kiplinger Letter. His other nationally distributed publications included a magazine called Changing Times, now known as Kiplinger’s Personal Finance.

While on vacation in the Stuart area when he was 61, Kiplinger impulsively decided to purchase the beautiful Bay Tree Lodge on the St. Lucie River. It became his winter retreat. During his winters in Florida, Kiplinger quickly became deeply embedded in the local community.

He made friends with a well-known sage of the Sunshine State, Stuart News editor Ernest Lyons. Lyons wrote about Florida the same way that Backus painted its backwoods and beaches. Kiplinger felt the same love for the local terrain. Lyons was so impressed with his fellow newsman’s devotion to the Treasure Coast that he dedicated his first book My Florida to his friend, “Kip.”

“Kip’s national reputation is based on simplicity itself,” Lyons wrote in 1956. “He has no ‘angles,’ no ‘pitches,’ calls the shots as he sees them with bedrock integrity.”

DOWN-HOME MOGUL

Kiplinger came from a small town in Ohio, and success did not remove his down-home charm. His beginnings in journalism were modest. But as an AP reporter and later a correspondent for a bank, he gained valuable access to government and business insiders who freely spoke their minds. He found that you can get to the honest truth when people don’t fear the consequences of spilling the beans. Kiplinger had the brilliant idea of publishing a low-cost letter crammed with facts he dug up from sources he kept strictly confidential.

Instead of hobnobbing with guys at the top who get caught up in spin, he befriended subordinates behind the scenes. They dealt in cold hard facts. Basically, Kiplinger turned unbiased investigative reporting into a media miracle — and he did it without advertising dollars. The forecasts he made from data he shared turned out to be so good, he made a fortune from subscriptions alone.

It is no wonder that Lyons admired the man. And it’s likely that Lyons was the one who introduced Kiplinger to that other fiercely independent, creative genius who was painting masterpieces in Fort Pierce.

ENTHUSIASTIC PATRON

When Kiplinger saw his first Backus paintings, it must have been love at first sight. He became an avid collector and spread the word about his discovery. To America’s beloved artist Norman Rockwell, Kiplinger wrote: “I am nuts about him [Backus] and his stuff, and you know how it is — you think everybody ought to be nuts about the same thing you are.”

Once when Backus sent him a couple of works by other Florida artists in his orbit, Kiplinger responded, “Beanie, I want more of YOURS. I don’t know why. It isn’t logical. I can’t put them [all] on my walls …. If you ever do a picture that you think is good, and for which you do not have an immediate sale, send it to me, will you, and bill me.” In that same letter, Kiplinger reassured him that it was not his intent to hoard the paintings as investments, but he would very much like enough to pass some along to his friends.

By the 1960s, the artist’s career really took off. Senators and governors collected his paintings, and one Backus painting would even hang in the LBJ Presidential Library in Austin, Texas. For the rest of his life, he would be inundated with commissions and his buyers were forced to stand in line. Eventually orders for his work would reach an estimated three-year backlog. His fame could have spread much farther, in his lifetime, if he had followed Kiplinger’s invitation to hold an exhibition up in Washington, D.C. There were Florida politicians up there, who were itching to show off the talents of a homegrown virtuoso. Apparently, Backus was focused on continuing the life he led.

BREAKING BARRIERS

It was a simple yet exemplary life, the way he kept his doors unlocked. His house was always filled with friends, many of whom were teenagers, later dubbed as “Backus Brats.” Some came to learn to paint, others just to hang out. Anyone was welcome in his home regardless of age, social standing or skin color. He flouted the harsh social laws of the Old South of that era, which made it unlawful for the races to break bread together in public.

Because of his great talent, the strict social order gave Backus a pass on rules that usually marginalized bohemians, people of color and so many others back then. Quite the contrary — his community rewarded him with accolades and a constant demand for his art. He shared his bounty with friends. He showed them how to paint their way around prejudicial barriers and find the kind of social acceptance that offers individualists the high privilege of being free to be themselves.

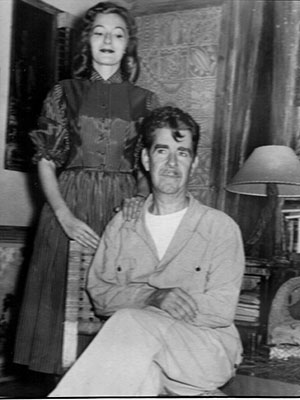

Much that has been written about Backus makes light of his heavy rum drinking. He made no bones about that. It was a part of his shtick when talking with reporters. He joked about it. Two drinks helped him paint; five drinks and he wasn’t worth a darn. But Michael Goforth of The St. Lucie Tribune astutely wrote that liquor buried a deep-seated pain, the source of which, Goforth speculated, had been the unexpected death of Backus’ wife. After only five years of marriage to the sister of fellow artist James Hutchinson, Backus had been so hopeful that heart surgery would finally heal Patsy’s life-threatening ailment. A doctor said her terrible result was a 1-in-5,000 chance. Backus said he led a lucky life, except for that longshot loss.

MAKING OF A HIGHWAYMAN

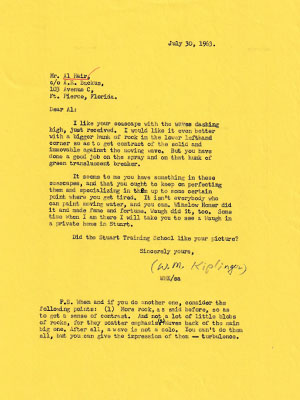

Backus introduced Kiplinger to the artwork of one of his most talented apprentices, Alfred Hair, a future member of the Highwaymen. He sold him one of Hair’s paintings. Kiplinger was so impressed that he commissioned another painting from Hair and carried on a correspondence with the young African-American artist.

“[Y]ou have the stuff,” he wrote to the budding painter who would soon influence other young painters in the area. “And you owe it to the world to do as much with it as you can.”

“I hope you will not be angry,” Hair wrote back to Kiplinger, “but by mentioning your name, I have been able to sell a great deal of paintings. My customers said, ‘If it’s good enough for Kiplinger, it’s good enough for me.’

“Once again, I thank you for your inspiring letters,” Hair continued. “It gave me so much spirit and reminded me in a wonderful way of my duty to the world.”

SHARING THE WEALTH

Like Backus, Kiplinger was well-known for being a humanitarian. The Washington Post once described Kiplinger’s media empire as having a share-the-wealth culture, so unusual for a large corporation during those times — or any time for that matter. For instance, Kiplinger bought his cherished Bay Tree Lodge to share with every single one of his employees and associates. Each was afforded a free Florida vacation, every year, in a setting with a view straight out of a Backus painting.

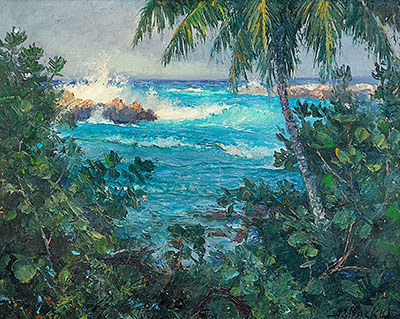

In fact, Kiplinger commissioned a large canvas mural painting of the view from Bay Tree. When Martin County built its first library, on land Kiplinger donated to the community, he shared the view by donating the Backus mural to the library, too. That painting, which nowadays adorns the Blake Library, will be part of the upcoming exhibit.

Kiplinger’s grandson, Knight Kiplinger, who cherishes the Treasure Coast region as much as his grandfather did, came up with an idea of how best to continue the legacy of his grandfather’s friendship with Backus, Alfred Hair and other gifted artists of the community. Through a generous gift, the Kiplinger family has endowed a section of the museum to be known henceforth as the Kiplinger Gallery. For generations to come, the new Kiplinger Gallery will help perpetuate the fame of Backus and artists he influenced.

TIMELESS HALL OF FAME

Backus was posthumously inducted into the Florida Hall of Fame for Artists in 1993. His sister, Laura “Titter” Nottage, accepted the honor on his behalf. She told a reporter that if her brother had been alive, he would have “shrugged it off.” He was so modest about his talent. She said he would rather be remembered as a humanitarian.

The fame of Backus as artist and humanitarian is worth spreading today. Many who have written about him have made much of how he has left a memoir in oils of a Florida that is vanishing quickly — or is already gone, perhaps. The miles of unspoiled beaches and idyllic woods were not endless after all. What once was an ordinary taken-for-granted fact all around us has been crowded out, and the past now seems like fiction. It’s true; his paintings can make us miss what we had. But if you look at them less nostalgically, in a majority of Backus’ Florida vistas there is an aspect of our exotic homeland that will never pass away.

In his book My Florida, Lyons wrote, “If you came to Florida and didn’t feel close to the clouds, you really didn’t see Florida.”

Backus felt close to the clouds. It’s obvious. Time and again, when young artists came to him wanting to learn how to paint, he took them outside to witness the play of light and color in the clouds, on the trees, in the water. His paintings are more than merely landscapes — they are skyscapes too.

Next time you look at Florida’s spectacular clouds, see if you can feel them as deeply as Backus did. Maybe it’s more than just a momentary sense of peacefulness they offer. There is a recurring illumination, which is still accessible to everyone who is open to looking through the artist’s eyes. How fortunate that A. E. Backus spent a lifetime replicating his inner sense of wonder about our natural world, day to day and year by year. And what a legacy it was — and is — for Willard Monroe Kiplinger and his descendants to celebrate the lasting magnificence of his friend’s great art.

See the original article in print publication

Nov. 15, 2023