Remembering a war hero

Firefight secures former officer and Vietnamese interpreter a place in SEAL lore

BY MARY ANN KOENIG

It was the first time the two men had met. Their Navy SEAL platoon was preparing a stealth night op out of My Tho in the Mekong Delta in Vietnam. Within the space of a few hours, they would be under attack, both would be badly wounded and evacuated to military hospitals. They wouldn't see each other again for 45 years.

But on that night in 1968 a bond of sacrifice was forged through a bloody confrontation with North Vietnamese guerrillas.

Retired Capt. Ronald Everest Yeaw, who made his home in Port St. Lucie, died June 21 having built a stellar 30-year naval career including three combat tours of Vietnam and as commanding officer of SEAL Team 6.

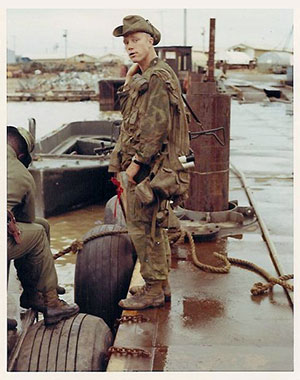

Ron and the Vietnamese combat interpreter Nguyen Hoang Minh were introduced as they stepped onto the patrol boat that would ferry them to their objective. It was a moonless night and the 7th Platoon, on a SEAL operation near Ben Tre, went out in search of an American POW who had gone missing from the 9th Army Division headquartered nearby.

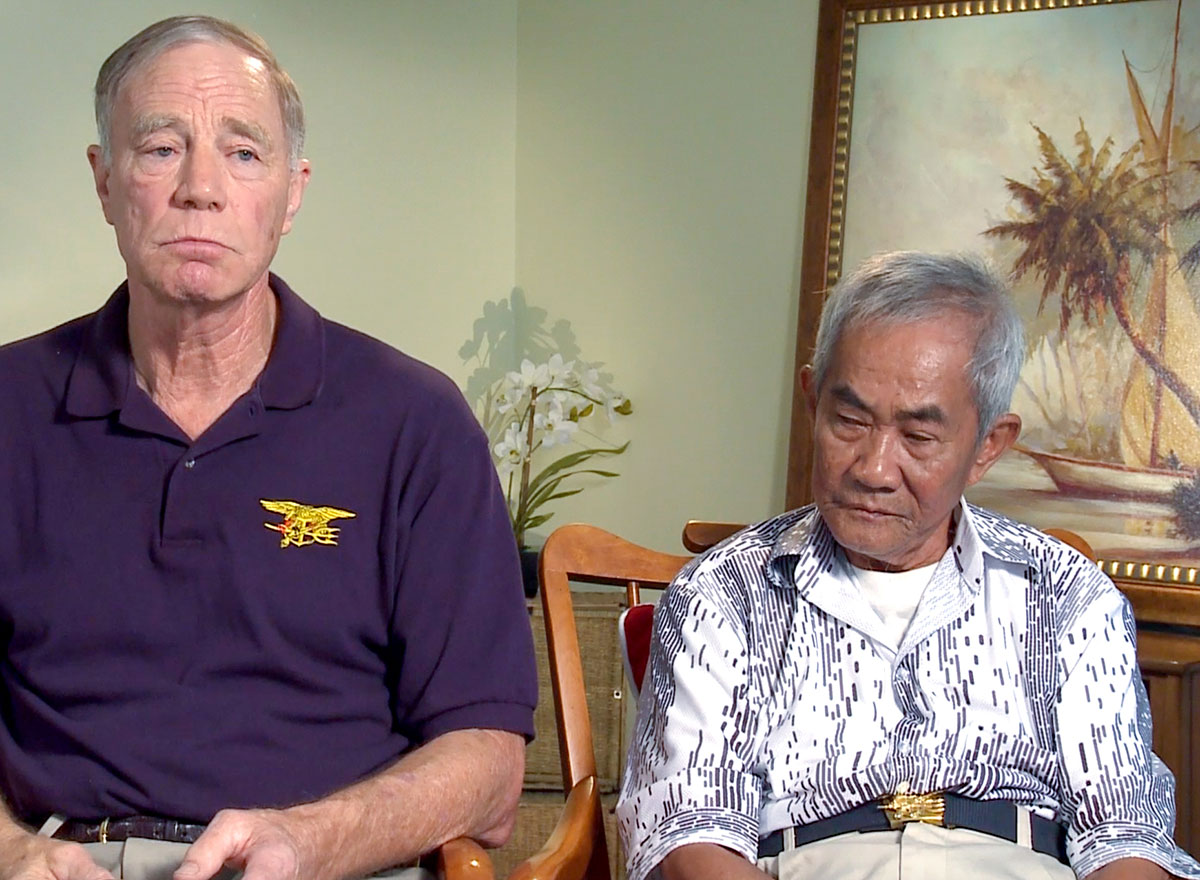

Forty-five years later, they were reunited at the National Navy UDT-SEAL Museum in Fort Pierce. I met both while making a documentary film, A Bond Unbroken, about their experience and the esteem and honor in which Minh was held by Vietnam-era SEALs.

in those days.

STUFF OF WAR MOVIES

Ron was the first person I interviewed for the film. His detailed explanation of what transpired that night is the stuff of well-crafted war film screenplays. But it was all too genuine. The operation, known in SEAL lore as the March 13th Op, has been written about and is considered one of the most harrowing SEAL operations of the Vietnam war.

It was Ron's first day operating with the 7th Platoon as replacement for Cmdr. Robert "Pete" Peterson's assistant, who had returned to the states.

According to Peterson, "Ron was joining a close-knit group of battle-hardened SEALs he did not know."

But on this first assignment with the 7th, Peterson remembered, "Ron's self-assurance, obvious physical prowess and previous combat experience won him immediate acceptance."

The platoon deployed in two squads that night, Peterson tapping Ron to lead one.

"Ron could have asked me to assign him a support role," Petersen said. "He had never worked with any of us and was facing leading a squad on one of the most complicated operations SEALs have undertaken. I would have accepted such a request as very reasonable. However, I don't think it even occurred to him not to be full in."

SEALs operated under a set of their own unwritten rules in those years. There were no commanding officers nearby. The platoons functioned entirely independently, planning and executing their own ops and answering only to a spot-rep that had to be written up after each action. There were no night goggles, no GPS, no overhead satellites positioning targets. They were armed, dangerous, exceptionally well trained - and utterly fearless.

On the night of March 12-13, both squads encountered the enemy and were forced to end the mission, never having found the POW.

Peterson's squad was pursued through heavily vegetated jungle, under fire by hundreds of Viet Cong, extracting via helicopter. Ron and his squad met the enemy inside a hooch that appeared to be a probable POW camp. Ron and three others, including Minh, were wounded by a tossed chi-com, a Chinese-made grenade.

My interview with him, recalling their encounter, raised the hair on my arms.

The territory was infested with enemy Viet Cong, and during the extraction fire fight, a lone medevac helicopter pilot was courageous enough to set down in a hot landing zone and pick up Ron and his wounded team.

THEY LOST TOUCH

After his recovery, through the next five years of the war, Minh worked with every SEAL platoon that came to My Tho. And then, they lost contact, and the SEALs he operated with often wondered about his fate, fearing he'd been killed.

When Minh was discovered alive in 2008, the SEALs mounted a gallant campaign for his immigration to the U.S. Ron, by then a retired captain, was one of the important voices supporting the campaign. His letter reads, in part: "I strongly recommend that Mr. Minh be accorded every opportunity to immigrate to the United States. We both shared our blood for a common cause and served that cause with distinction."

But Minh's visa request was denied.

Instead, the SEALS raised funds to bring him to the states for a reunion with his old comrades. Ron was there to greet a man he'd known for only a few hours but with whom he had shared a lifetime of scars and repercussions.

Minh had taken shrapnel in the chest and abdomen, spending weeks in an Army hospital. Ron, with numerous wounds, including a nearly severed foot, was evacuated to a hospital in Japan and then to Philadelphia, where he recovered. He would return to Vietnam voluntarily for two more tours.

In the 2013 reunion at the SEAL Museum, Minh didn't immediately recognize Ron. But then, he beamed, calling out repeatedly, "Mr. Yeaw, Mr. Yeaw!"

Ron was a man of amazingly droll humor and humanity. He leaned into Minh and said, "I'm the one who got you all shot up, all along here," indicating Minh's right side. Then he smiled and said, "You're welcome."

Their handshake, embrace and recognition of the price each had paid before arriving at this point, represented more than just a shared military action. It was an indicator of the unique connection that they, and only a few others, could comprehend.

The next two hours they poured over a hand-drawn rendering Ron had made of the hooch and surrounding area, reliving the operation and its etched details, including the long slog to the medevac helicopter, Ron hobbling on one leg using his weapon as a crutch, Minh being carried by members of the squad. Additional helicopters, Sea Wolf pilots, coming in to lay down cover as they extracted. The laboring medevac struggling to take flight with the heavy load of too many passengers.

"I was squeezed in between the pilot and co-pilot, and I could see the red-light indicator," Ron recalled in our interview. "The pilot pulls the stick, and not much happens, we got one foot in the air and the helo starts taking fire, it's shaking like an SOB. It moves forward a bit, slowly gets up speed, tips forward, has enough air, and finally gets off the ground shuddering the whole way." He had clarity aplenty of the night's events.

STELLAR YEARS OF SERVICE

The rest of Ron's career is an impressive legacy of service.

He became Joint Special Operations Command chief of staff at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and commanding officer of both SEAL Team 6 and UDT 21. At the Pentagon, he served on the Special Operations staffs of the Secretary of Defense and the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Academically, his credentials are no less inspiring. He attended the Navy War College and received a master's degree in national security affairs from the Navy Postgraduate School. During his career he was awarded 45 medals and ribbons including the Defense Superior Service Medal, the Navy Legion of Merit, nine individual commendation medals with the Combat V for valor, including four Bronze Stars and the Purple Heart.

In retirement, Ron served as director of ambassador relations for Project Lifesaver. The nonprofit organization, with Florida headquarters in Port St. Lucie, trains and equips public safety departments nationwide with electronic radio searching capabilities to locate persons with cognitive disorders who've gone missing.

He also worked for the G4S Professional Armed Security Corp. for 13 years.

Peterson didn't see Ron again for several years after that fateful 1968 night.

"I started to apologize for getting him shot up," Peterson said. "But he interrupted me, saying 'BS Pete, that was the night I became a SEAL.'

That attitude was what earned Ron the respect of his teammates throughout his career."