The Best of the Best

Lincoln Park Academy marks 100 years of striving for academic excellence

BY BERNIE WOODALL

By nearly any objective measure, Lincoln Park Academy is one of the best high schools in St. Lucie County and the state of Florida.

Test scores and advanced courses have often spoken of the resounding success of Lincoln Park Academy since 1923 when it began as a salve by the white school system to parents who wanted something unusually rare for African Americans in Florida at the time — a chance for their children to go beyond the eighth grade.

In the century of its existence, Lincoln Park Academy has evolved from a celebrated segregated school to a conventional integrated one to an award-winning traditional magnet school. It now has an International Baccalaureate program rated in the top 15% in the country. Its academic story alone is an important part of the history of Fort Pierce and St. Lucie County.

What sets the school apart from other educational institutions is its central role in the historically black section of Fort Pierce, especially before public schools in Florida integrated in 1970.

At a time when blacks had to go to the back of Burger King to get a hamburger or use a back door and the balcony at the Sunrise Theatre, African Americans looked to Lincoln Park Academy with a sense of pride and dignity and as an avenue to a meaningful future.

Its position at the pinnacle is shown by the fact that the community surrounding the school took the school’s name as its own. What was once known as the northwest section of Fort Pierce, or other offensive monikers, is now the Lincoln Park Community.

Lincoln Park Academy’s faculty from day one embraced the notion of developing more than just teenage minds.

“All of our teachers were African American,” Ernestine Trice English, LPA Class of 1957, said. “One thing about having all the teachers looking like us is that we had a real sense of who we were and what we could accomplish. The teachers were concerned about our studies but also about the whole person.”

Walter Pierce Jr., Class of 1961, said the influence of teachers extended beyond the school boundaries.

“When I was growing up in Fort Pierce, our faculty members lived in the community,” Pierce said. “We saw them on the weekends. We saw them after school every day. We could not misbehave when we were out of school because they saw us.”

English concurred. “The teachers were kind of like extra aunts or uncles. They would stop you if they saw you doing something wrong. And you wouldn’t have to tell your mom when you got home. They had already called and told her.”

THREE EPOCHS OF LPA

This year, Lincoln Park Academy and its far-flung graduates celebrate the school’s centennial.

LPA has had three distinct points of history.

The first, from 1923 to 1970, is the segregated era. Near the end of this period, white teachers began moving over to Lincoln Park. By the academic year of 1969-70, nearly a third of the teachers were white, but even at that late date, there were no white students. Probably the biggest event in this span was the opening in 1953 of a new campus where the school still stands, at Avenue I and North 17th Street, from its Means Court and 13th Street location.

During the second, LPA transformed in 1970 to an integrated school for all ninth graders in the county school system. Later, it became a middle school.

And the third epoch, which began in 1985, continues today. Partially to appease a federal judge, who had to approve the county’s attendance zones, LPA became a magnet school with a traditional education theme in a highly successful attempt to draw students from all over the county. The first student body’s racial makeup of 53% white, 44% black and 3% other was close to that of the school district at the time.

EARLY ADOPTER OF BLACK EDUCATION

Samuel S. Gaines, LPA Class of 1956 and son of Alma Stone Gaines, Class of 1937, is an unofficial historian of the school. Gaines, who served on the school board for 34 years, said the first school for African American children in Fort Pierce was in 1906 in an old tin building on North Eighth Street that the white school system had used for storage. Soon, a new building replaced that tin one. It is not clear if that early school had a name other than the Colored School. Sometime before 1920, the school moved to North 13th Street and Means Court and became known as Means Court School.

Not everyone agrees that 2023 should be LPA’s centennial year. Francenia [Fran] Tripp Mimms, Class of 1959, said it would be more appropriate to celebrate the year that the school first included all four high school grades. She said she has tried to find out when that was and suggested that it was either in 1926 or 1928. Her mother, Ann Tripp, Class of 1934, started going to the grade school in the 1920s.

“If you want to go back to celebrate when they first started the school, then go all the way back to 1906,” Mimms said. The 81-year-old lives in Fort Pierce near the current LPA, an area she says was called Tuskegee Park.

In a history of black education in St. Lucie County, Gaines said, “In 1921, there were only 18 Negro pupils in the twelfth grade in the three four-year high schools in the entire state, and none of them was accredited.”

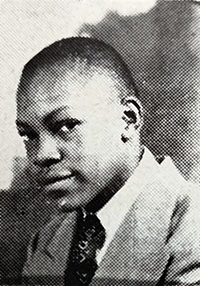

In 1923, James Espy was principal of a vocational high school in Sandersville, Georgia, when he was convinced to lead a high school for African Americans in Fort Pierce.

The school, which became Lincoln Park Academy, opened in September as a junior high school with five ninth graders. The community wanted more. Parents packed the St. Paul AME Church to tell the county schools superintendent, W.E. Riggs, they wanted a full four-year high school. Riggs said they could have it if they raised $1,600. They raised $2,600.

Espy knew the importance of the school having a solid name. Some wanted it named after the principal, but Espy demurred.

In November 1924, The News Tribune reported that the county board of public instruction “granted the request of the colored Parent-Teachers Association to name the local colored school ‘Lincoln Park Academy.’”

There were few school supplies and no dictionary. When Espy asked for a dictionary, it was diverted to St. Lucie County High School. Later the white secondary school was renamed Fort Pierce High School and finally Dan McCarty High School. McCarty, member of a pioneer family, was the only Fort Pierce native to serve as Florida’s governor. He died at age 41 in 1953, when he was only eight months into his first term.

Espy’s requirement that LPA teachers have bachelor degrees and a demand for academic rigor set the Fort Pierce school apart from the beginning.

A 1927 survey of Florida State Department of Education schools found that “Education among Negroes in Florida is very spotty, ranging from very good at Lincoln Park Academy down to the very poorest.”

And the tradition continues. LPA has received an A from the Florida Department of Education every year since 2002. It rated in the 96th percentile of the nearly 24,000 U.S. high schools in 2022 in the annual U.S. News & World Report rankings, first again among St. Lucie County public high schools, as well as 42nd in Florida for public high schools with at least 400 students.

MULTI-GENERATIONAL

Pierce, now 78, was a career social worker who then earned a doctorate and taught at Barry University. His mother, Eva Elizabeth Pierce, who went by E. Elizabeth Pierce or E.E. Pierce, taught English at Lincoln Park from 1930 to 1963, the year she died. She was instrumental in the formation of the school newspaper, and its yearbook, The Moon.

The Pierces are among many families with multigenerational links to LPA. In addition to the writers who were covered in classes at white high schools, E.E. Pierce taught from the works of African American authors such as Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston. Hurston was a substitute teacher for a short while at LPA in the late 1950s and lived in a small house next to the school provided her by Dr. C.C. Benton. It stands today as a historical structure with a monument to Hurston outside.

Walter Pierce was in one of the classes that Hurston taught. He and Earl Little, former LPA choral director from 1955 to 1970, said that for most students, Hurston was more odd than compelling. She dressed like someone who cleaned floors for a living, Little said.

“The students didn’t know what a jewel they had,” he said.

LPA LEGENDS

There are plenty of notables who are linked to LPA beyond Hurston. LPA graduate James E. Hair in 1944 was one of the famous Golden 13 who were the first blacks to be commissioned as officers in the U.S. Navy.

Another member of the same family was Alfred Hair, who became one of the Highwaymen painters now celebrated on the Treasure Coast.

Little was valedictorian of the Class of 1944. After a prestigious college career and teaching at Southern University in Louisiana, Little was LPA’s choral director for 16 years, then moved over to teach at Fort Pierce Central, which was the school created when Dan McCarty and LPA merged in 1970. Like many of LPA’s students in its first few decades, Little’s parents had little education and worked in farm fields and citrus groves around Fort Pierce.

Little, 96, lives in Dothan, Alabama, with a daughter now that he’s survived two wives. He still drives and shops for himself, but he’s not fond of night driving. He comes back to Fort Pierce around Christmastime every year to hand deliver his homemade fruitcakes, which he dutifully did just a few weeks ago.

From the Class of 1968 is Lee Ernest Rhyant, who went on to be executive vice president at Lockheed-Martin Marietta after leadership positions at Rolls Royce Aerospace, Detroit Diesel Allison, and as a plant manager for General Motors. He is a highly sought business and leadership consultant who lives near Atlanta.

He credits Little for being a role model for him.

“I got my core skills from the family, the church and the school,” Rhyant said. “Earl Little was involved in all three of those for me.”

Rhyant recently published Soaring that is part autobiography and part advice for business executives, which he wrote with a college professor.

That first day of the merged senior classes, students were told to report for an assembly on campus. The two student council presidents, Rhyant and Dan McCarty’s Carol Strange, were called to the stage. And a simple act of friendship, Rhyant said in an interview, helped disarm what could have been a violent situation.

“She politely reached out her hand to shake mine,” Rhyant wrote. “Carol could have refused to touch me or could have simply ignored me, but her generous act set the tone for the next two months.”

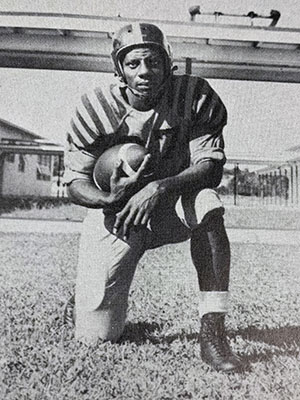

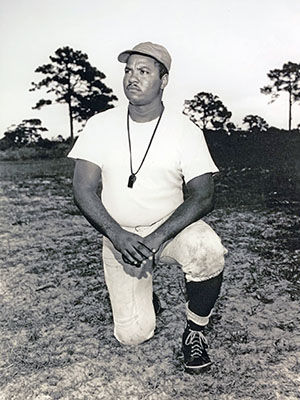

Robert Jefferson was the longtime coach of orange-and-black clad sports teams, most notably football, at LPA. Later, he was principal at Fort Pierce Central. Jefferson was at LPA when part of the faculty’s job was to spruce up the new place.

“Instead of playing sports in PE class, Mr. Jefferson had us out planting grass seeds,” Gaines said of his first months at the new LPA when he was in the 10th grade.

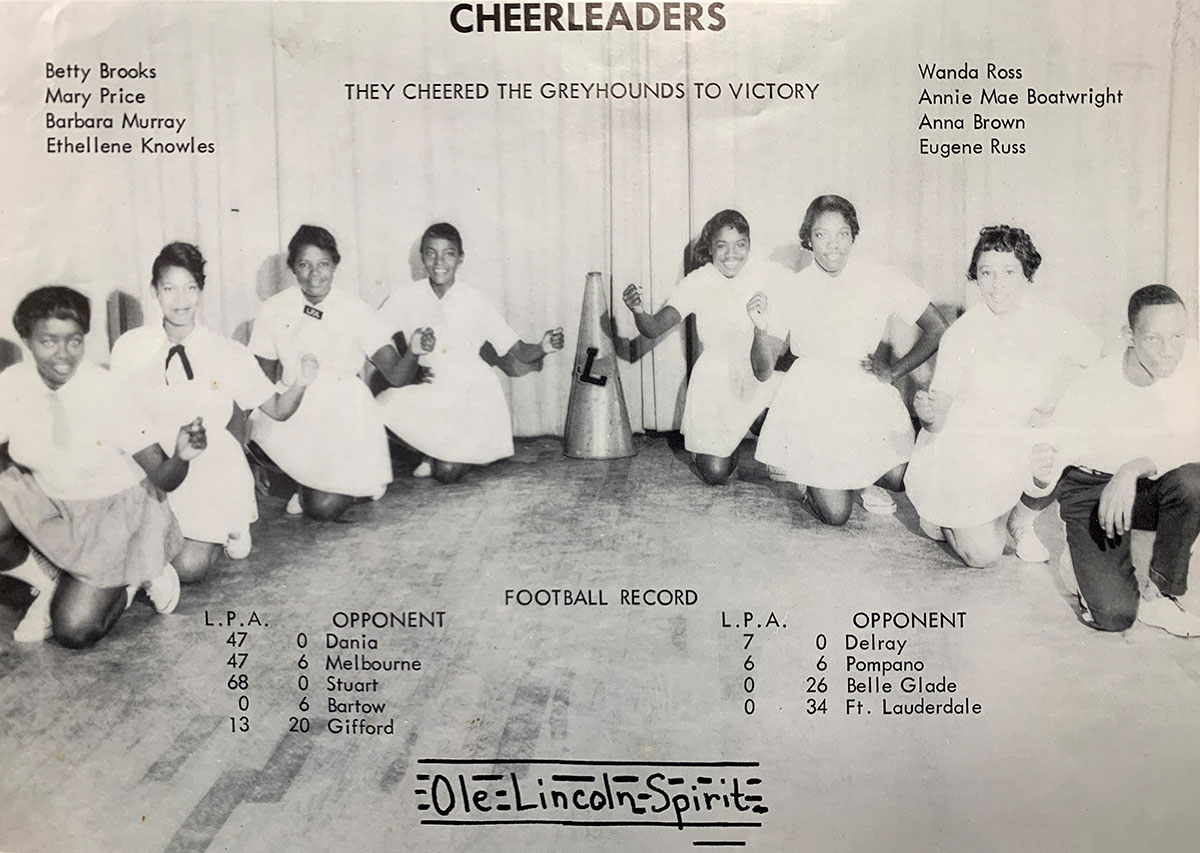

Before the move, Jefferson coached the 1952 football Greyhounds to a perfect season in seven games when it outscored opponents 152-21.

Even in the early days, LPA produced outstanding sports teams. The Greyhounds won the first state championship for black high schools in 1930, then won it again in 1932.

Gaines is a story himself. He turned 85 in January, and can still be frequently seen at Stone Bros., the funeral home his grandfather started in 1932 on North Seventh Street. He is a former president of the National Funeral Directors & Morticians Association. He was a St. Lucie County School Board member for 34 years, a span of years that included LPA’s transition to a magnet school. And then there is the kindergarten-to-eighth grade Samuel S. Gaines Academy of Emerging Technologies on Jenkins Road.

MAGNET AFTER SOME DOWN YEARS

In 1985, partly to satisfy federal District Judge C. Clyde Atkins who was required to approve St. Lucie County’s school attendance zones, Lincoln Park became a magnet school and drew students from throughout the county.

There were some excellent teachers and students in the years between segregation and magnet school, but, by 1985, the quality of education at LPA had slipped, as explained in a December 1984 Miami Herald article. “Lincoln Park does not match the quality of other county schools, officials say, and the time has come for renovations and a new, stronger emphasis on academics.”

The idea was to attract white students to LPA without forced busing, by offering a back-to-basics and rigorous academic program with strict dress and behavior codes.

Rik Gray was on the original faculty of about three dozen when LPA’s magnet program opened to 642 seventh and eighth graders. Later, he was named St. Lucie County Teacher of the Year in 1997 and retired as social studies department head in 2018, the last of the original LPA faculty.

Gray praises Elizabeth Lambertson, LPA’s principal for the first 10 years as a magnet school.

Gray said Lambertson told him she was scared that no one would show up when LPA asked parents to come to the school to apply for their children to be the first in the magnet program.

“She told me when she got there early in the morning, the line was around the block,” Gray said.

From that first year, newborn babies were added to the waiting list for LPA.

In the 1990s, soon after Rachel Cuccurullo and her family moved to Port St. Lucie from Hollywood when she was 5, her parents applied for her to attend LPA. She stayed on that wait list for 10 years before she got what she called her golden ticket in the mail telling her she has been accepted as a 10th grader.

She said her long wait was typical among her friends. But by the time she was accepted she had set her student life up at Centennial High School in Port St. Lucie and declined. She was in the Centennial Class of 2007.

FRIENDLY, FAIR AND FIRM

John Lynch joined the LPA faculty in 1986, the second academic year it was a magnet, stayed 15 years, and was named St. Lucie County Teacher of the year in 1998. Lynch said, “We had a solid group of teachers at Lincoln Park. Exceedingly good teachers. We built good relationships with the kids and good relations with our colleagues.”

He said his approach was like that of many of his colleagues at Lincoln Park: friendly, fair and firm.

Lambertson’s efforts at Lincoln Park were hailed in 1991 when she was one of 10 named an American Hero in Education by Reader’s Digest.

Each year that first class of eighth graders continued as LPA added a higher level each year and by the 1989-1990 school year, it had all four high school grades. It graduated its first class in 1990, 84% of whom went on to college.

WE DO RIGHT…

The mere fact that parents choose to send their children to LPA means that they are likely be higher achieving than those at more conventional middle and high schools. But the advanced classes that were once unique to LPA are now offered at other county high schools, allowing them to draw students from throughout the county to their schools. The waiting list is not as long these days but parents still register newborns for a chance to be a Greyhound, said Henry Sanabria, LPA’s principal since 2014.

LPA’s graduation rate is more than 99% and, because the state rounds up, is officially 100%. Most of its students are still high-achievers and college-bound.

Two are Alexandra Watson and Caitlyn Difilippo, both juniors who got into LPA as sixth graders because they were in the program for gifted students. Watson is in the IB program and is thinking about attending either the University of Chicago, the University of Pennsylvania or the University of Florida. Difilippo has her sights on Flagler University.

“What sets us apart is the academics,” Difilippo said. “And Lincoln Park’s legacy is profound. LPA is definitely a cut above. Most people in the county know that. It’s purely statistical. We are always, always No. 1.”

Watson said she chose to go to LPA rather than the school she is zoned to attend because it gives her the most options after she gets her high school diploma, and she loves her teachers.

The school district decided when LPA began that it would not have a football program, and while it excels in other sports, the main one for most high schools is absent.

“I’m not going to lie,” Watson said. “I do miss having a football team.”

Their energetic principal, Sanabria, said, “It’s all about developing culture and maintaining the traditions. You have to change with the times but you don’t change to the point where you forget your traditions. The tradition of excellence had always been maintained, and the culture is what keeps that going. The school motto says it all.”

That motto was created by the students who moved in 1953 to the new LPA on 17th Street from the old one on 13th Street and were subjected to frequent admonishments from faculty not to mess up the new place.

The original motto was “No One Has To Tell Us What To Do. We Do Right Because It Is Right To Do Right.” Over time, the first sentence of the motto was dropped.

See the original article in print publication

© 2023 Fort Pierce Magazine | Indian River Magazine, Inc.