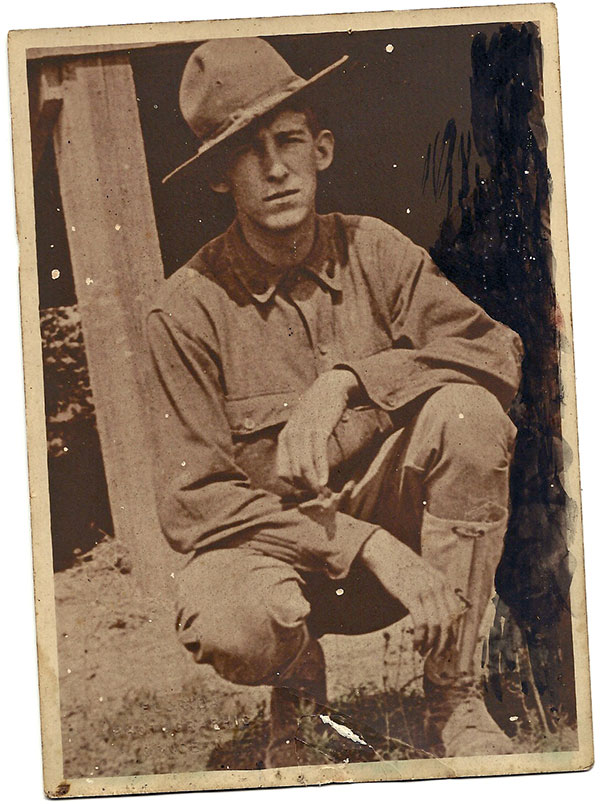

‘Our Soldier Boy’ of World War I

This photo of Stephen N. Gladwin, after whom the Fort Pierce American Legion post is named, is apparently the only photo of him that survives today.

One hundred years after the death of Stephen N. Gladwin, a descendant puts together the long-forgotten pieces of his life

BY GREGORY ENNS

The name Stephen N. Gladwin was a familiar one to me growing up in Fort Pierce.

I first saw the name etched in the World War I memorial monument on the grounds of the St. Lucie County Courthouse, undoubtedly after seeing a movie at the Sunrise Theatre across the street. My dad pointed out the monument one day and though he probably said exactly how he was related to us, for years we just knew him as “one of our relatives.’’ Whenever we congregated around the monument after movies, I’d often boast that I was related to the name on the top right of the memorial.

The local American Legion Stephen N. Gladwin Post 40 also carries his name, and by extension the American Legion baseball teams the post sponsored over the years.

At graduation from high school, I received something called the American Legion School Award from Stephen N. Gladwin Post 40, a bronze medal that has been long since lost.

It wasn’t until I was older that I realized exactly how Stephen Gladwin was connected to me. He was the older brother of my grandmother, Margaret Gladwin Enns, and of my great uncle, Bob Gladwin, the leader of the local Sea Scout ship with whom I’d grown close over the years. Thus, Stephen Gladwin was the great uncle whom I only knew by name and who had died long before I was born.