Life Lessons

Dedicated teacher’s efforts put youngster on path to success

BY ANTHONY WESTBURY

In second grade, Alvin Miller missed more than 90 straight days of school. He simply went AWOL when he realized he was out of his depth. When he was in the classroom, he terrorized students and frustrated his teachers. It took a seventh grade teacher to recognize the good in him. She turned the boy around to excel in school, college and in life.

Rita Marie Johnson was a young teacher in her 20s at Dan McCarty Middle School in Fort Pierce when Alvin was assigned to her class in 1973. She knew him by reputation from other teachers. He was simply out of control, unable and unwilling to learn anything.

Johnson saw him like a horse that needed breaking before learning could happen, thus the title of Miller’s autobiography, The Horse.

Alvin was by no means the first difficult black male student Johnson had come across.

“In every family there are kids like Alvin,” Johnson said. “I’ve taught several Alvins in schools where I’ve worked.”

It was her knack of reaching young black males that the principal of Dan McCarty, Nolan Skinner, noticed. Alvin had come up against the judicial system and was about to be expelled from school. Yet Skinner wanted to try one last option before he completed the expulsion paperwork.

LAST CHANCE

He turned the youth over to Johnson to see what she could do with him in seventh grade.

He’d failed to graduate from any of his prior classes but had been socially promoted to the next grade anyway.

“We had a few battles,” Johnson recalled of the first few months with him. “He wouldn’t follow any rules. He walked on tables in science class, he encouraged other children to rebel in gym class.”

Alvin’s home life was one of detachment and neglect. His single mom, Elizabeth, had nine other children. She worked incredibly long hours as a fruit and vegetable picker and then took a second job in a bar at night. She simply was too exhausted to give her son the attention he so desperately needed.

Alvin, his teacher quickly realized, was tough on the outside but really was a caring individual underneath the bluster he’d learned on the streets and hanging out in migrant labor camps every summer with his extended family.

His desire to do well underneath all the bad behavior was the way to open up his best qualities, Johnson decoded. Her odyssey with Alvin wasn’t restricted to the classroom. She visited his mother to learn more and to ask her permission to take a large role in disciplining him. She readily agreed.

In The Horse, Miller notes over and over how ill-prepared he was for school. He never attended kindergarten or other preschool classes. While other kids could count and knew their colors and some even were on the verge of reading, he was completely lost and overwhelmed. He simply gave up trying to learn and did what he wanted.

That included running away from home and living on the streets for months. He ended up in Judge Jack Rogers courtroom where he was suspended for the remainder of second grade. The judge threatened to send him to a notorious reform school in Tallahassee if he ever came before him again. For once, Alvin listened to an authority figure.

GRADUAL CHANGES

The student and teacher began working together one-on-one and gradually changes in him emerged despite his reluctance to behave any better.

“I told him he’d have to get to my house every day before school to complete his homework,” Johnson recalled. “My husband, Jimmie, and I had all the books and encyclopedias he needed. He made the honor roll that year and never looked back.”

Miller notes in the book how success in school and Johnson’s attention were like a drug he craved. Life just became simpler and easier once he started to cooperate.

Miller loved football and was a star running back in high school. Johnson and her husband began going to his games and even took him to college and professional games as far away as Miami.

“We saw things were changing in him,” Johnson said. “During my teaching career, I saw lots of Alvin Millers. Not everyone made it; they failed to be consistent or had no parental support.”

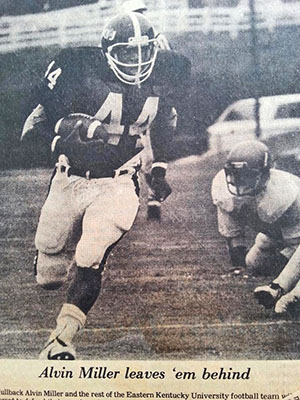

But Alvin had the equivalent of two mothers rooting him on. He embraced all the positive strokes that were being given to him and went on to a string of successes that took him through middle and high school and on to Eastern Kentucky University where he became a star running back with the nickname Horse while attending the university’s large ROTC [Reserve Officer Training Corps] program.

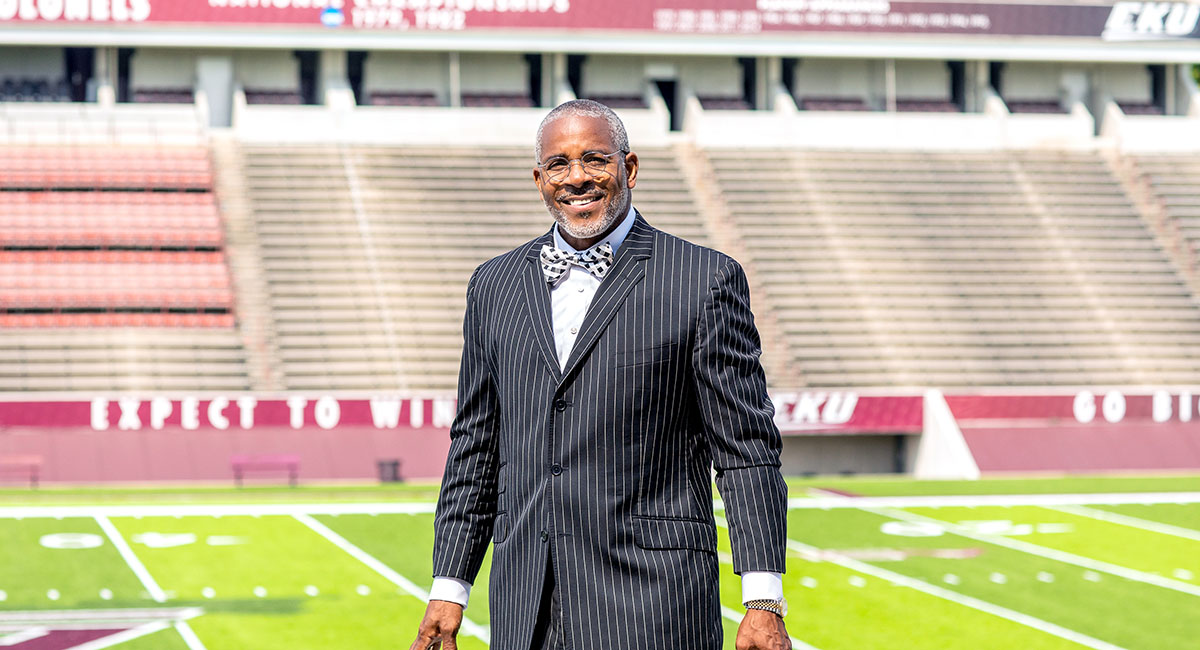

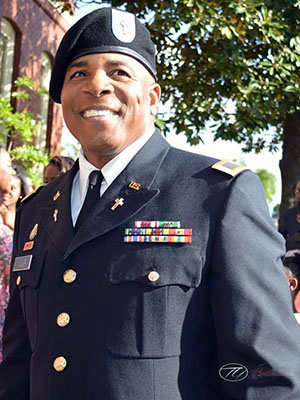

Later he joined the Army as an officer, studied for a doctor of theology degree, became an ordained minister and, after 10 years teaching, returned to military service as a chaplain. He retired after serving for 30 years. His proudest moment came during a visit by President Barack Obama to Fort Campbell, Kentucky, where the team that took out Osama Bin Laden trained. Miller was chosen to give the invocation, an honor he cherishes.

STILL IN TOUCH

Miller and Johnson remain tight today. She’s now 75 and retired in 2005, but she’s still a very important part of his life.

Miller, 63, lives in Nashville, Tennessee, but is a frequent visitor to his hometown to check on his mother [now in her 80s] and his old teacher and godmother. Miller and Johnson talk by phone almost every day.

“I think he sees me as a combination of his older sister and his godmother and as a second mom,” Johnson said. “My family is his family and always will be. It’s been an amazing ride. I can talk about him for hours.”

Miller writes in The Horse that even during his worst days in school, before Johnson, he always wanted to do well, he just didn’t know how.

Rita Johnson showed him how. She showered him with attention and love — something that was missing at home. He blossomed into a prized student and has gone on to enjoy a life of success. He could easily have ended up behind bars or even in the electric chair. He notes how two boyhood friends were executed, while others are still on death row.

Today, Miller is happily married with grown children. He gives back to Fort Pierce through his role as a founding member of Restoring the Village. He’s paying forward all the love and attention a teacher gave him.

See the original article in print publication

© 2023 Fort Pierce Magazine | Indian River Magazine, Inc.