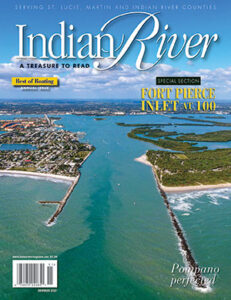

Fort Pierce celebrates inlet’s centennial

Events to mark the day the Fort Pierce Inlet and the Atlantic Ocean met a century ago

BY ANTHONY WESTBURY

It was the biggest party the young city had ever seen.

Almost the entire population of Fort Pierce [fewer than 2,000 people] took to the streets on May 12, 1921, to celebrate an achievement that had been more than 10 years in the making: the cutting of a new inlet that “married the ocean and the Indian River.”

The daylong celebration included the city’s first parachute jump, boat rides, parades and speeches, a community fish dinner, a big local baseball game, concerts and a street dance.

It was a moment for chest-puffing civic pride.

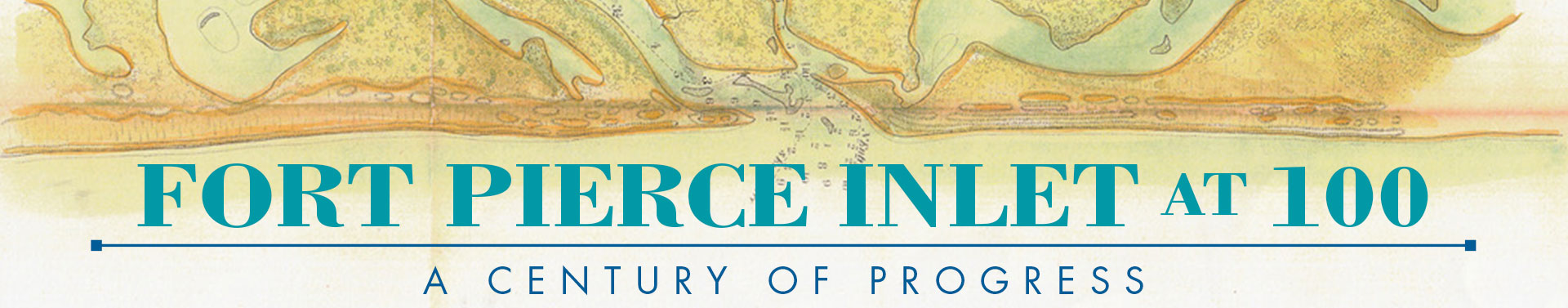

There had long been an original inlet that linked ocean and river. It was a mile or so north of downtown across from St. Lucie Village, meeting the Atlantic at a point roughly where present-day Pepper Park stands.

Yet the old inlet had proved barely adequate for the flat-bottomed fishing vessels that used it most frequently. The inlet was notoriously unreliable; it shoaled badly after storms and often was plugged up with sand and silt. Boats often had to be dragged over land, sometimes requiring tree trunks to be used as rollers. Finally, by the early years of the 20th century, it closed up for good.

As long ago as the 1890s there had been attempts at improving the inlet. Sporadic dredging had taken place, but storms inevitably quickly closed the gap.

Local commercial fishermen began to look for an alternative. After a couple of unsuccessful attempts at digging a new inlet on North Hutchinson Island, attention turned to south of the city.

In 1913, fish house owner Richard Whyte organized an expedition to Mud Creek, at a point immediately north of where the St. Lucie Nuclear Plant sits.

Whyte shipped mules and scrapers on barges down the river. At first, his efforts looked promising. The mules were able to cut a channel through to the ocean, but a storm quickly washed all the excavated material back into the new cut.

Worse yet, a group of bears then living on the almost uninhabited island got into the mule’s corral and stampeded the terrified beasts all over the island.

All work ceased and never occurred at that site again, despite at least one attempt to try again a few years later.

Meanwhile, efforts to cut a new inlet in roughly the same position as the current day channel began to crystallize. The Indian River Inlet Association formed around a group of local businessmen, including hardware store owner and mosquito control pioneer, Will Fee.

From about 1916 onward, the group generated voluminous correspondence and studies of the feasibility of cutting a new inlet immediately east of Fort Pierce.

In February 1916, they agreed to survey land in the area of Tucker’s Cove, just west of the present Inlet State Park.

Cost estimates ranged from $13,950 for a 100-foot-wide and 5-foot-deep channel to $5,550 for a 30-foot-wide version. The U.S. War Department expressed interest in the project but insisted on the posting of a $20,000 bond to pay for any damage to navigation on the Indian River. This additional burden put the project on hold for another two years.

By 1918, the clamor for a viable inlet was mounting. During the 1919 Florida Legislative session, state Rep. Richard Whyte enacted a bill allowing the inlet district to levy taxes to excavate and maintain a new inlet.

Revised cost estimates for a channel and jetties projecting into the ocean had soared to $76,500.

In March 1919, Tucker sold the inlet district commission a 400-foot strip of land through which the new channel would run.

A public vote authorized an $80,000 bond issue to cover construction costs. Shortly afterward, the Seaboard Dredging Co. began work.

The inlet digging was keenly followed by the public through the pages of the Fort Pierce News Tribune. By May 1920, the paper excitedly reported the dredge was within 50 feet of breaking through to the ocean. Work would stop while the stone jetties were put in place.

On May 8, 1921, the final few feet of sand were removed around 8 p.m. and the ocean – three or four feet higher than the river – rushed through, scattering the dredge and taking barges and equipment out to sea.

For the next few days, the strong 6-knot current in the inlet gradually subsided as the water cut its own channel. At first, small boats had had trouble negotiating the current, even running at full power.

The grand opening was set for May 12. All local businesses would close for the afternoon. The celebration would begin at 9:30 a.m. with the first parachute jump ever seen in Fort Pierce. Then free boat rides would allow residents to inspect the new inlet up close. After speeches by local and state dignitaries, a fried fish dinner was served to hundreds by the Women’s Club for 20 cents a plate.

That afternoon, the Fort Pierce baseball team got into the spirit of the day by thrashing rivals West Palm Beach, 9-1. Band concerts and a street dance completed the day, allowing excited locals to let off a little steam.

The whole town, including motor cars, was decorated with flags and bunting. As the News Tribune, brimming with local pride, noted, “the celebration should be made to eclipse all other celebrations on the East Coast, for the inlet is worth it and the St. Lucie County people do things that way.”

Yet, while the new inlet was certainly a step forward, the creation of a modern deep-water port didn’t happen for almost another decade. For one thing, the channel was only 7 feet deep, inadequate for commercial vessels.

Until now, Fort Pierce’s most famous winter visitor and the inventor of Crayola Crayons had not gotten himself involved in the inlet effort. But in 1923, Edwin Binney agreed to become a director of the inlet district. He began to form his own vision of what Fort Pierce could become.

It quickly became apparent that enlarging the inlet and creating port facilities was becoming out of the reach of local financing efforts – despite boom times in Fort Pierce in the 1920s, when property values skyrocketed until evaporating following the 1929 stock market crash.

In 1923, $220,000 was raised to extend the jetties and deepen the inlet to 14 feet. In 1925, another bond issue for $400,000 was approved by voters. Spoil created by the latest dredging was used to form a causeway across the river, roughly in the same position as today’s South Bridge.

Successive bond issues reached $600,000 and the wider, deeper inlet and a new channel reaching the mainland, including a turning basin, was handed over to the new Fort Pierce Port Commission in 1929. By now, railroad sidings had been added to the port area and the city constructed a large warehouse on the waterfront.

The first commercial cargoes of lumber had been arriving via sailing schooners since 1925, but the new port officially opened for business in February 1930 with the arrival of the Baltimore & Carolina Lines’ 250-ton freighter Betty Weems, and thrice-weekly service to Baltimore, Philadelphia and New York.

Binney had been instrumental in financing the last few years of port development. Along with using his own personal fortune, he spared no efforts enlisting government aid. In 1932, as a result of Binney’s connections, the U.S. War Department agreed to take over the port with an initial commitment of $250,000 for further improvement and maintenance and $50,000 a year for continued upkeep.

The new port posted a marvelous cargo record and Fort Pierce became one of Florida’s leading shipping points for citrus and vegetables. Binney’s final contribution to the port was the construction of a state-of-the-art refrigeration terminal built where Derecktor Shipyards is busy creating its mega yacht repair and refit center.

Once the refrigeration terminal became operational in 1935, Fort Pierce became the largest handler of perishable goods and the state’s largest commercial fishing port. The new plant was served by three railroad sidings and boasted a deep-water slip alongside the building. A slat conveyor system could move fruit at a rate of 60 boxes a minute directly into the holds of waiting ships. The plant handled citrus, meat, eggs, poultry and vegetables and served agricultural interests within a 100-mile radius of the city.

Sadly, Binney never got to see his latest creation. In 1934, while traveling from his home in Greenwich, Connecticut, he died after suffering a heart attack during a stop in Gainesville. He was on his way to inspect the new plant before it began operations.

World War II halted all operations at the port and after the war, railroad and trucking companies dropped their shipping rates to render coastal shipping impractical. The port never recovered and has remained in the doldrums ever since.